From the Archival to the Fictional: How "Where to, Marie?" Revives Local Feminist History

Editor’s Note: In the interest of full disclosure, we note that “Where to, Marie” was funded by Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung's Beirut office, a main partner of The Public Source.

The recently published comic book, “Where to, Marie? Stories of Feminisms in Lebanon," distills a century of overlooked feminist struggles through the stories of five fictional characters.

The personal stories of Marie, Nidal, Haifa, and Noora, introduced through the book's protagonist Lara, showcase some of the roots of varied feminist movements in Lebanon, exploring how these movements emerged and later developed through challenging historical periods. The intent, according to the book's creators, is to remind readers that “women’s issues” are and have always been revolutionary priorities.

The Public Source's Christina Cavalcanti and Yara El Murr interviewed the co-authors of the book Bernadette Daou and Yazan al-Saadi and four of the comic artists, Tracy Chahwan, Sirene Moukheiber, Joan Baz, and Razan Wehbi. The fifth artist, Rawand Issa, could not be present at the time of the interview. The book was originally written in Arabic and translated into English by Lina Mounzer.

The interview, edited for length and clarity, delves into the research, artistic process and teamwork that birthed the book through these tumultuous times.

Bernadette, the stories developed for the comic book primarily draw on your thesis. What questions were you pursuing and what methodology did you adopt in your research?

Bernadette Daou, researcher and co-author: I'll start with the methodology: it was ethnographic work. It's mainly interviews with a lot of activists from different generations. It was also from a very close perspective, from the inside of leftist and feminist movements and spaces that I’ve been active in since 2000. It was at the intersections of all my identities. I had a lot of questions myself that I wanted to explore in depth.

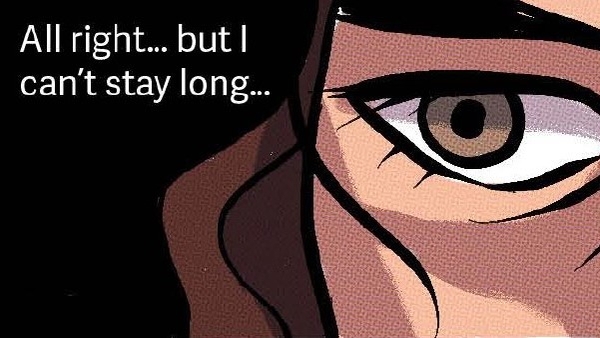

A close-up of Lara’s eyes, who has just been invited to join a group of women in Azarieh to discuss her earlier confrontation with men. Source: The Meeting in “Where to, Marie?” p. 3. Artist: Razan Wehbi.

Can you tell us about the process of translating your research from academic language into the comic format? You took a relatively large body of work and turned it into a very different format. What informed your selection process?

Bernadette Daou: It's the first time that I write in the Lebanese Arabic dialect and the first time that I write for a comic. Yazan was the person who introduced me to this world; I couldn't have imagined an approach like this. What was interesting to me was meeting all of the activists, getting to know them through the interviews, sometimes living with them… You don’t give space to the personal when your goal is to write an academic text. I had to write my thesis in French, in a foreign language. If I had to write the comic book in classical Arabic, using all the terminology, you would be choking yourself, your language, and the language of the persons who shared their lives with you. Even before I finished and defended the thesis, I was searching for ways to publish some of the results in this way.

We decided to personalize history. We didn't want to talk about big moments, but about personal stories collected in characters that are fictional.

In our process, we decided to personalize history. We didn't want to talk about big moments, but about personal stories collected in characters that are fictional. I didn’t imagine that I would write the thesis in this way, but it came organically.

Yazan Al-Saadi, co-author: I remember one of the things we tried to imagine, and maybe it was a dangerous thing to do, was how to synthesize an entire generation into basic characteristics, from hairstyle to use of transportation. What Bernadette presented was a huge bulk of powerful information… an intellectual research of facts. Academic writing is so inaccessible, so it was a great opportunity for me to rework it into a format that is both powerful and accessible.

What role do you think the comic medium plays here? You said accessibility is really important to you. Can you talk a little more about why you chose this medium and the political motivations behind it?

Yazan Al-Saadi: I chose this medium because I am a fanatic of the medium and there’s a long history of Arab comics. I think this project was really on a nexus of a lot of important aspects. Here is a comic book that deals with a very important part of our history, created by voices of this region, in a format that is everything that is the best and most awesomest parts of who we are and where we are. Comics are very public and popular. It works because of art and text playing together. It is a format that we should be using more and more as weapons of communication and thought and ideas.

Tracy Chahwan, illustrator of Nidal’s Story: Growing up, we didn't really hear about feminist struggles or what female activists did. I never had the reference growing up. Comics give life in a different way. We can tell these stories and illustrate them in a way that you wouldn't see otherwise because archives of such stories don't exist.

Razan Wehbi, illustrator of the intro and outro: I agree, I think the journey that we've had to take to learn about these things, the history of feminism in Lebanon, was tough. You have to do your own research, dig into archives that aren't easy to access... And this being a comic, it’s not complex, it's well-structured, and the language is simple without trivializing their experiences, which was important to us. I think anyone can read this, scholar or student, they can read this and learn something from it.

Nidal and her friends at university aspiring to achieve great change. Source: Nidal’s Story in “Where to, Marie?” p. 19. Artist: Tracy Chahwan.

In terms of the artists you collaborate with, how was the creative team brought together? What informed your selection process?

Yazan Al-Saadi: Bernadette and I had broken down the story into the idea of five characters. We wanted each chapter to be embodied by a certain artistic style. It was important for the artist to be a woman, from the area, not necessarily Lebanese, but has lived in Lebanon or can visually connect to the context.

Bernadette Daou: We sent many artists the script, and we met online with them. How they interacted with the story was also part of the selection for me.

Yazan Al-Saadi: When we went to them with the script, there was no ending. The fact that they were able to trust us to develop a collective ending to the story was cool. I don't know if you guys freaked out when we came with a two thirds script, really...

Razan Wehbi: Yazan and Berna were trusting us with this work that was obviously very precious to them and trusting us to embody these characters properly. And there had to be trust from our side because an ending wasn't written yet. Maybe in other projects, the owners would make those decisions, but there was a lot of trust and love involved from both sides and that’s what helped it come to life the way it has.

[T]here was a lot of trust and love involved from both sides and that’s what helped it come to life the way it has.

Joan Baz, illustrator of Haifa’s Story: When Yazan approached me, it was exciting to be part of a project that invites you to do your own research. You get text, but you don't really get into it unless you research the era, watch videos, look into archives, and that in itself was enriching on a personal level.

Sirene Moukheiber, illustrator of Noora’s Story: And I remember when I first read the script, I only had three pages for Noora but I fell in love with her from the first three lines.

What about the real people who made it into this book? How did you pick figures like Warda Boutros, the first woman martyr in the fight for labor rights?

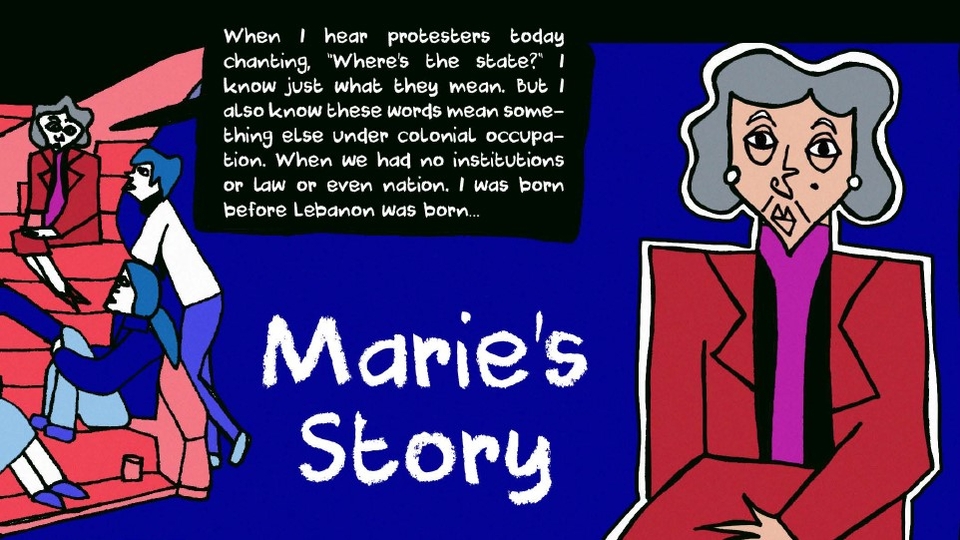

Bernadette Daou: We have this official story of independence, as if nothing existed before it. It is written by big men, rijallat al-isteklal, from the bourgeoisie who are well-connected on the international level, and had the privilege to write their story. The workers’ struggle was an important part of getting independence, but when they established the Lebanese state, they didn’t legislate the labor law to protect the workers. When they created the electoral law, they discriminated against women, so women didn't have the right to vote.

This generation thought that by demanding a state, this would protect workers' rights through labor laws and social security. That didn't happen, so the struggle continued.The feminist movement has always historically drafted and recruited women from other movements: from the workers' movements, from the student movements, from the leftist movement. So it was an important way to show linkages through these women. For example, Warda Boutros, in parallel to the story of independence, like Rawand has greatly put in front of each other, we got independence, but the struggle hasn't stopped. They killed Warda Boutros after independence. This generation thought that by demanding a state, this would protect workers' rights through labor laws and social security. That didn't happen, so the struggle continued.

Along with the historical characters, there were also historical junctures that were weaved into the stories including the first Israeli invasion and the civil war. Can you speak about these choices?

Bernadette Daou: The study is articulated around four waves of women and feminist struggles in Lebanon if we want to start at 1943 with the movement of the sufragette. Each wave developed from a context. For example, from a nationalist struggle for independence to a leftist wave in the 1970s. That was also inspired by the rise of the new left in the same era; new because they saw that our societies, our movements, and the national independence regimes, are the causes behind which we lost the war. The third wave, which saw the light in the conjuncture of the reconstruction of the country after the civil war was the rise of a globalized feminist agenda. A Lebanese delegation participated in the Beijing conference that is mentioned in the script. And a fourth wave emerged within another new left now in 2000, and it was inspired by the Second Intifada, the liberation of the south, and an opposition movement within the old left, so these are the large epochs.

Marie, the eldest of the group, imparts some of her wisdom to the younger women who have collected to tell their stories. Source: Marie’s Story in “Where to, Marie?” p. 6. Artist: Rawand Issa.

Let's now go chapter by chapter to ask each of the comic artists to tell us about the relationship they developed with the characters of their stories. Razan, how did you work on introducing "Lara" in a way that created the scaffolding for all the stories that followed hers?

Razan Wehbi: I could work so well with the chapter because I saw myself in Lara. It was the same journey I had, the same anger — minus meeting four amazing women at the age of 20. I had her questions, “why isn't anyone talking about this?”or “why haven't things changed? Why have things taken so long and why do we still see so little progress?” And I think we could all relate to learning about feminism and joining the movement when you're younger, especially in university, so it's disheartening and destructive at some point.

I could work so well with the chapter because I saw myself in Lara. It was the same journey I had, the same anger.But seeing her talk to these women and realizing that it's not a journey that ends with us, it doesn't end with Lara, or Nidal or Haifa… We accept the fact that we’re working towards a bigger goal. By the outro, you could see the contrast in the sense of calm that they had — not calm as an acceptance, but they know the drill, they know what everyone's going through and understand that it is about working towards the next generations. It really builds that power inside of you to keep carrying on in spite of the difficulties and the lack of progress. I don't want to ruin anything, but there is some really nice character development that was translated visually.

I think that's a great description without spoilers. Let's jump to Nidal's story next, as illustrated by Tracy. It's your favorite era. The 1970s, starting with the Suez War and continuing throughout the Lebanese civil war. Can you talk about the work that went into illustrating these difficult historical moments and seamlessly integrating Nidal into them?

Tracy Chahwan: I was really visually inspired by that period of time. The history of the civil war is so rich and there’s so much to dig into. I watched so many documentaries and I learned a lot. I was also really attached to Nidal because she reminds me of my parents and their friends. I've met women that are a lot like her, who were activists during that time. I quickly visualized the look of the character and the vibe I wanted her to have. The hard part was to use all this information, all this documentation, and to reduce it to a chapter.

We're going to move to Haifa's story next. Joan, Haifa's story is mainly focused on placing Lebanese feminist movements in a wider, global context, and there's a focus on NGO work. Can you talk about the research or the references that you used to recreate these conferences, the delegations, even the signs on the buildings?

Joan Baz: This chapter delves into the early 1990s with the end of the civil war and takes it on from there, so it's a period I grew up in and it goes on to the present time. It was interesting to understand the core and the birth of all these campaigns that we're used to seeing today, like campaigns by KAFA, ABAAD, and other NGOs working on feminist issues. It was an awakening to understand how these NGOs became hostages of their own funders. What I like about this book is that it highlights not just the success stories of these movements, but also looks critically on the relationships between these NGOs and on issues related to their internal functioning.

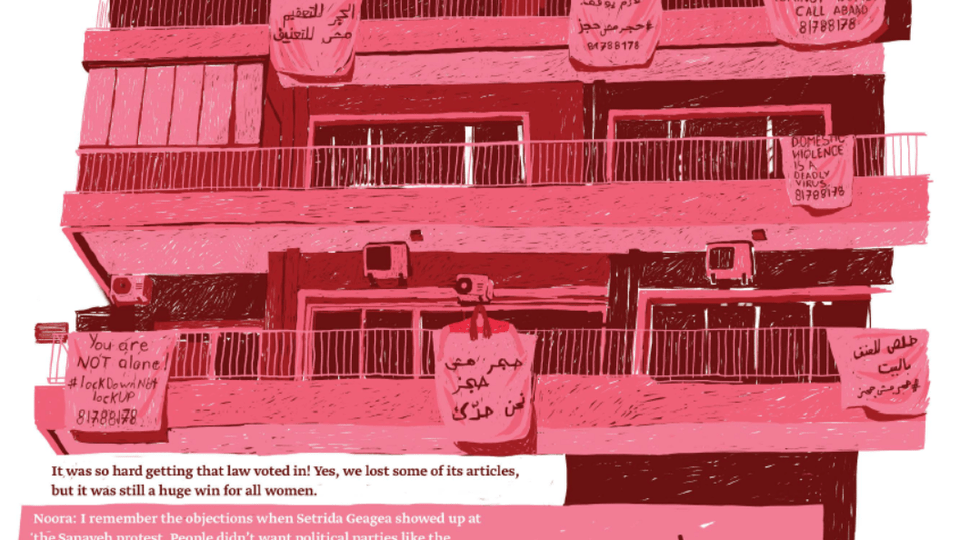

It was an awakening to understand how these NGOs became hostages of their own funders. There is a lot of auto-criticism, and criticism within each other because they keep lashing out at each other, and that's something you will notice when you read the book. Each generation would have done things differently. And a lot of things were also latched onto Haifa in particular, like “why are you taking such a stance that is very similar to the government's?” It’s all part of the politicization of NGOs, and how they would be forced to take such stances based on the agendas of their funders. My chapter kind of draws light on that period. One of the campaigns is a very recent one done during the lockdown when women put their blankets out on the balconies and wrote ABAAD's number on it. So there’s the big picture and the little details.

Bernadette Daou: I’d like to add something here. I was amazed to see the result, how Joan depicted the NGO-ization process in a pyramidal way, it blew my mind. The process was productive because of the research done by each artist.

NGO representatives stand at the top of an organization's pyramidal structure, illustrated according to Haifa's experience of working in and with them. Source: Haifa’s Story in “Where to, Marie?” p. 31. Artist: Joan Baz.

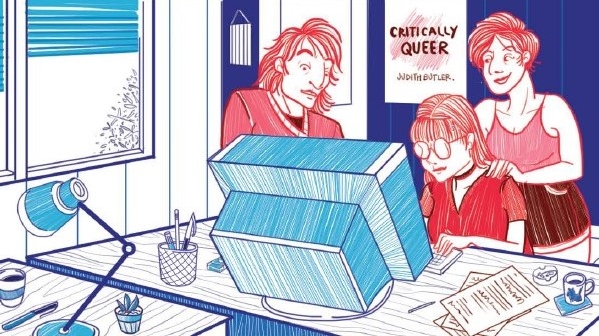

Noora's story partly tackles the issue of intergenerational conflict between feminists, but of course, her story is more complex. It is ultimately about daring to dream or imagine alternatives and a brighter future. Sirene, did illustrating this piece bring you solace in these dark times?

Sirene Moukheiber: I had the easiest chapter research-wise because it's our time, we lived it. So it was more of character work. When I first read the script, I smiled a lot because I saw myself in the rebellion, the curiosity, the hope. I felt that I can really relate to that, and I want to express it, so I made her more fun and bold.

When I first read the script, I smiled a lot because I saw myself in the rebellion, the curiosity, the hope.

We found it interesting that we hear from all of the women except for Lara. Why doesn't she share her story? What does Lara represent?

Yazan Al-Saadi: I'll be very direct and speak about the elephant in the room: when we're talking about feminism, and as a man engaging with this topic, my role here is to sit, listen and support. So coming with that spirit, and looking at Lara’s character, I did not feel right trying to define an endpoint to the voice. I wanted to represent the character as accurately as possible in terms of what I saw of the amazing women that are in the struggle, but it was not my place to define her voice.

Bernadette Daou: Yes, thanks Yazan for the step back. For me, it’s also because we are interrupted by a flood. When we got first approval from Rosa Luxemburg to fund the project, it was right before the intifada and also it was in the time when my family and I were boiling underneath, in terms of economic situation, like relatives losing jobs. We also saw the flood of people in the streets. We saw a new generation that we don't have the right to define. Lara for me represents this generation that is interrupted by also a second flood, which is the coronavirus. A lot of things would have been different, so we really don't know where we're going in terms of the society and the social movements in general. So we don't know a lot about the new generation, and we are all interrupted, in a way or another - forced to go back to stages below zero, to provide our daily food and medicine... We are in a crisis that obliges women to go back to these very basic things to do... The movement is almost non-existent on the ground.

Lara, tired of being talked over by men, puts on her jacket in one of Martyrs’ Square tents as she storms off. Source: The Meeting, from “Where to, Marie?” p. 2. Artist: Razan Wehbi.

I want to bring us back to the form, and my question might be more relevant to the artists who were illustrating these stories. How did you work together to ensure some sort of continuity in the book while maintaining each of your personal styles?

Razan Wehbi: Bernadette and Yazan never wanted us to lose our individual style because it was very important to show each character's perspective.The difference in style worked in our favor, taking us between time periods and taking us to historic places and different feminist waves. How do we achieve the look of a single story? because yes, we're going through these different time periods, but it's still one story being told. And a lot of that was just us going back and forth. We were tasked with, “this is your character, design it and then share it with the rest.” One of my favorite moments was receiving those sketches from Tracy, Joan, Rawand, and Sirene, and drawing it in my style but still staying true to that character. It's like drawing a celebrity or someone who already exists. And they became so real to us. So it was challenging at first, but I think the key term, again and again, was the communication between us.

Joan Baz: Other than having, as a constraint, the characters, we had a frame that we all needed to start and end with. This really was a very smart decision taken by Yazan and Berna to make sure that there's a link between each chapter. Having a restricted color palette also added to the homogeneity of the chapters. It was very interesting to see how each artist interpreted this color palette. The artistic direction helped bring everything together.

Yazan Al-Saadi: What we were trying to do here, at least structurally, was to play out the best things that come out in the process of making a comic, and it's creating these linkages and collaborative systems. Because the book is an anthology, it demanded linking through storytelling, and that's what we mimicked a lot. Whether it was in content or in the form itself through the framing, and the color palettes.

Noora and her independent group of women meet in an office to organize, educate themselves, and to write articles about their personal experiences. Source: Noora’s Story in “Where to, Marie?” p. 42. Artist: Sirene Moukheiber.

To wrap up, what do you hope readers of this book will come out with? What do you want them to stay with?

Yazan Al-Saadi: Let's hear from you actually. You read it. So what was the impact?

Yara El Murr/The Public Source: I'm not used to interviewees turning the table on me. At first, I was really intrigued. It's something that, as many mentioned before, we don't have a very solid knowledge of. Maybe we've heard of some of these events, but not from a feminist perspective. Reading the book was enlightening. I could relate to Lara because she's closest to my age and we live in the same era. But seeing the other histories gave me an appreciation of everyone who's fought for us to be where we are today. So that's my takeaway. Chris, do you want to share yours?

Christina Cavalcanti/The Public Source: I think reading it made me appreciate all the work that women have put in for us to have even the few freedoms we have today. It also made me realize how far along we still need to go. By showing all of us what's been done, you're also showing us how much work there's still left to do. It’s a call to action, especially now and especially here.

Bernadette Daou: Wow… I’m surprised. I hope that it would be a funny and also serious way to tell stories. There is a lot more. I hope it gives you some information about what has been done. How we can imagine, maybe.

Tracy Chahwan: For me the best part is the intergenerational narration. It's something that we should do more in real life and to ask women from other generations what they've been through and what it was like to be active during their times. I would have loved to have a book like this when I was younger and to have learned about all these women, so I'm hoping this book can inspire the reader.

I would have loved to have a book like this when I was younger and to have learned about all these women.

Joan Baz: Yes, people tend to forget what others have done for us to get where we are today, even if we have a lot to criticize. Everything was done within its own context and limits.

Razan Wehbi: One of the most important things was seeing that women and feminists are different. They have different ideas and ideologies and experiences, they clash with each other. It's not one umbrella that everyone fits under.

Thank you all for being in conversation with us. With this year’s International Working Women’s Day occurring in the middle of a pandemic, barring us from being physically together, this book ties us to not only today's women in struggle but to those who fought before us.

“Where to, Marie?” has a limited free print release and is available online in both English and Arabic.