Beirut’s Feminist Library: A Home to Writings from the Struggle

The Knowledge Workshop ورشة المعارف (KW) is a feminist collective, knowledge producer, and the only independent publisher of feminist books in Lebanon. When Deema Kaedbey and Sara Abu Ghazal came together in activism over a decade ago, they started thinking about how to join organizing and feminist knowledge production. Over time, they conceived KW as an “ongoing workshop for (re)searching and gathering women’s stories.” In 2016, they opened the KW space in Furn El Chebbak and launched their ongoing oral history project to pursue forgotten and untold feminist histories in Lebanon, now under the name the Storytelling and Oral History Project. Five years later, KW published its first book, تسعينيات نسوية Feminist Nineties, an edited volume gathering personal essays by women from the feminist movement of the nineties, as well as accessible research on multiple histories of feminist organizing in postwar Lebanon. A second edited volume will come out later this year, tackling feminism and ecology. Today, KW’s growing archive and publications have become an incomparable reference for anyone invested in feminist knowledge and praxis in Lebanon.

As part of its labor of love for the feminist struggle, KW is home to The Feminist Library, whose catalog includes 1900 books, brochures, journals, and magazines. On March 10, 2022, The Public Source visited KW to learn about how this library has evolved and what a feminist might expect to find there. Kaedbey, director of the Knowledge Workshop, shares that the first books on the shelves were her own and those of Abu Ghazal, KW’s co-founder and former co-director. Gradually, the library expanded with the help of feminists and allies donating books and with funds to grow the library more intentionally. Visitors will find a sizable collection of women’s writings in Arabic, particularly novels, biographies, and memoirs. Readers can also browse through Arabic-language academic books and journals in gender studies and cultural studies, including every volume of Bahithat and al-Raida. Beyond Lebanon and the region, the library is also home to many books by women-of-color feminists and queers.

The Public Source spoke with some of the people actualizing KW and asked them what’s their favorite book on the shelf and why. Their answers are slightly edited for clarity.

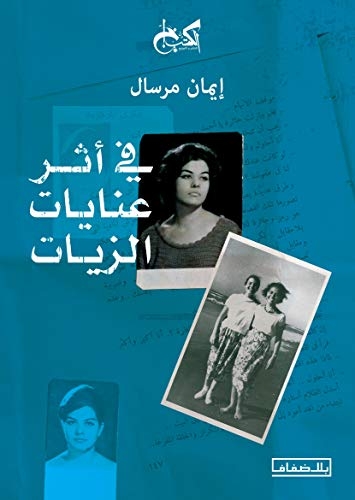

Iman Mersal’s في أثر عناية الزيات [Fi Athar ‘Inayat al-Zayyat] (2019), Trans. in French Sur les traces d'Enayat Zayyat (2021)

When Egyptian poet and novelist Iman Mersal read the only novel of ‘Inayat al-Zayyat, an Egyptian woman and writer who killed herself in 1963 at the age of 27, she was haunted by questions. Who is ‘Inayat al-Zayyat, and why is her novel not part of the Egyptian literary historiography when works of lesser “aesthetic or political” significance are included? In 2014, she began to “follow the trace” of ‘Inayat al-Zayyat. “To follow the trace is to dig after the questions this character poses,” she said in an interview with France 24, “questions about the historical moment, the individual moment, psychiatry, law. You ask the archive questions, and you test it. You’re not just looking arbitrarily for what it presents you with because the archive is multiple and contains many bits, some complementary, others contradictory, and so on.”

Safaa, co-editor of Knowledge Workshop Publications, describes how this book speaks to her in the following terms.

Safaa: This is my favorite book here because of how it’s written. First, the language is smooth; then, it’s a woman writing about another woman, following her story, the story of a writer who killed herself. So Mersal follows al-Zayyat’s life and asks many questions: like what drove her to kill herself, the pressure of being a writer, her work being recognized or not, mental health, and so on. In a sense, it’s relatable. Mersal follows the trace, as the title of the book suggests. She contacts al-Zayyat’s friends and family; tracks publishers and authors who worked with her; visits her cemetery to find out why she was buried in a side room and not with the family; and looks for her in what was written about her. She gathers hints, then something small leads to another. Not long before reading this book, I had been reading Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar (1963), so it was powerful to see connections, like mental health and societal pressure on women, across time and space.

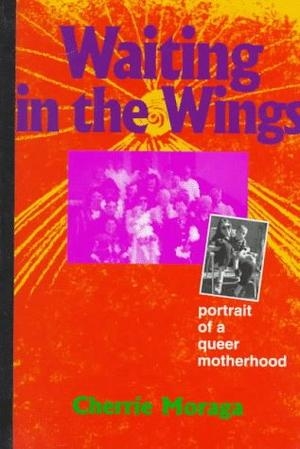

Cherríe Moraga’s Waiting in the Wings: Portrait of a Queer Motherhood (1997)

Moraga is a Chicana lesbian writer, feminist activist, and playwright, co-editor with Gloria Anzaldúa of the women-of-color classic feminist anthology This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, first published in 1981, now in its fourth edition. Waiting in the Wings (published by Firebrand Books, one of the earliest US publishers of women-of-color, feminist, and lesbian authors) is a memoir of queer motherhood and a premature baby’s struggle for survival. It is largely based on the writer’s journal entries during and after her pregnancy. Here’s what Deema Kaedbey says about it.

DK: I’m trying to remember, the first time I read it was around 2008-2009. It opened my eyes to the possibilities of [the different] kinds of stories to tell, and how to tell them. It's beautifully written. I had known Moraga, and I love her work, like Loving in the War Years [1983] and The Last Generation [1993]. And with this book, it was very moving the way she wrote about themes like life and death, writing, queerness, and motherhood. I taught it in undergraduate classes when I was a teaching assistant at Ohio State University, and students usually connected. Sometimes [I assigned it for classes] with students who came from more conservative backgrounds as a way to start thinking about LGBT people and parenthood. [I also assigned it in classes where students] got deeper levels or more themes of the story.

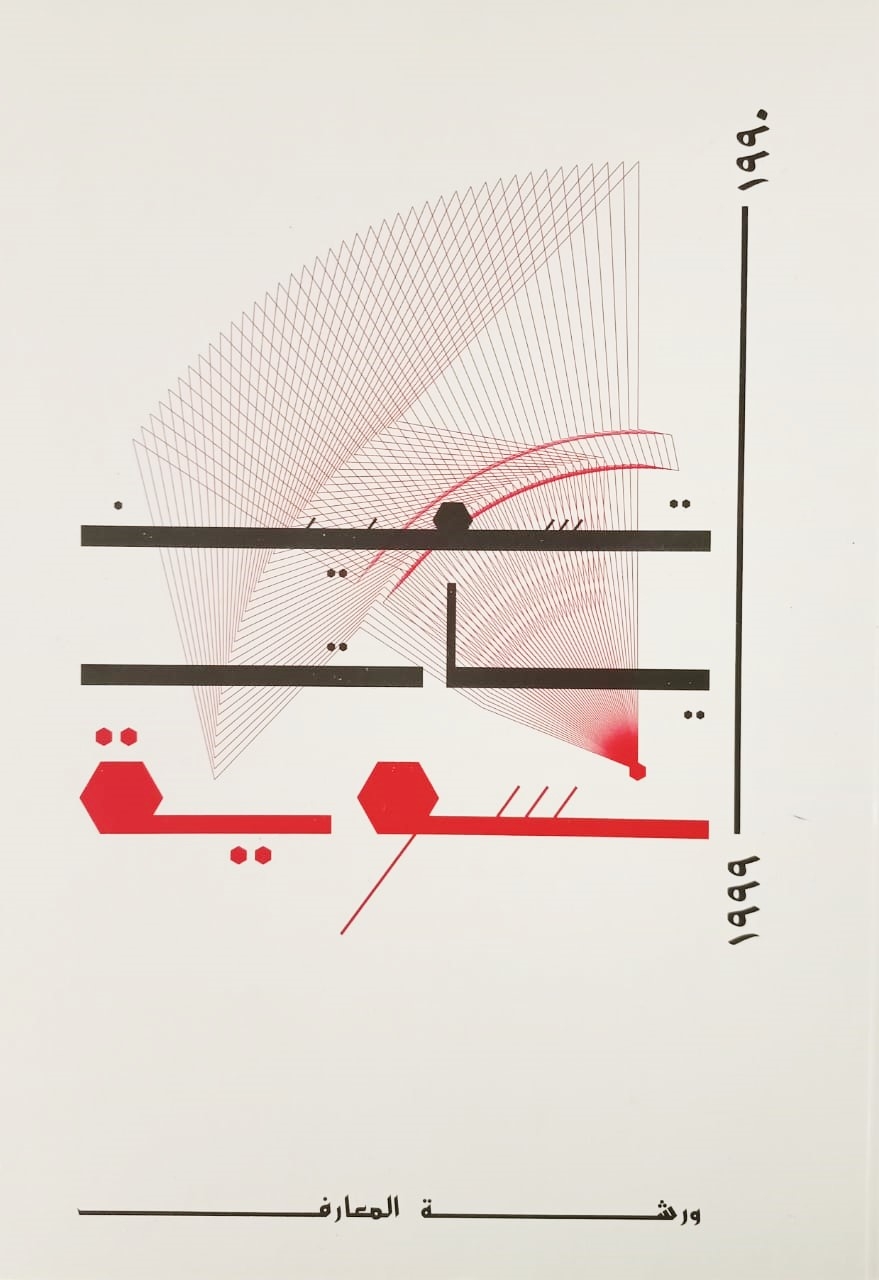

The Knowledge Workshop’s تسعينيات نسوية Trans. Feminist Nineties (2021)

This was Zainab Al-Dirani’s pick. She is Projects Officer at KW (disclosure: the author of this piece contributed two chapters to تسعينيات نسوية Feminist Nineties).

ZD: I love this book besides the sentimental value attached to me being part of the team working on it. If I remove that from the equation, its importance lies in what the stories in it changed for me on a personal level. I had never before been able to find myself while reading the history of this country and this book changed that. It made [being part of this place’s history] a reality for me. It made me understand a lot about postwar Lebanon, and how it is connected to what is happening today, as well as how the politics of amnesia shaped both landscapes and cities, as well as the people who inhabit them. But also, it helped me grow closer to the movements I’m involved in, like how far back they extend, what they have been through, and how they’ve evolved. I was able to feel more for the people around me and the history they had to navigate. I also think the collaborative process of this book is important because it involved a lot of conversations with so many people, researchers, different feminists across generations, and this is what made this book. Some oral histories were transcribed almost verbatim, with very slight editing, and we made sure the interviewees have complete agency of what they want to be written about them and how they want to tell their stories. And finally, it centers people and groups who have never been centered elsewhere. There’s clearly a lot more to cover but Feminist Nineties is an entryway to this rich personal and collective history.

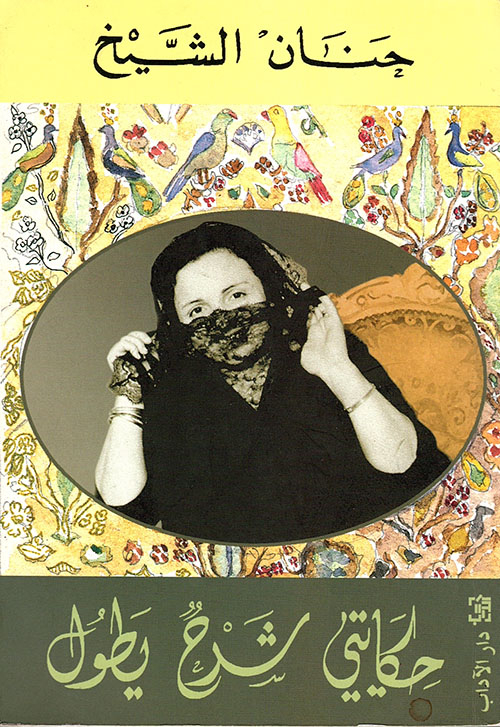

Hanan al-Shaykh’s حكايتي شرح يطول [Hikayati Sharhun Yatul] (2005). Trans. The Locust and the Bird: My Mother's Story (2010)

Lebanese novelist, playwright, and journalist Hanan al-Shaykh wrote a memoir of her mother Kamila that describes her personal life in history between Nabatiyyeh and Beirut since the 1920s. This is Deema’s second pick.

DK: I found it to be such a great story of her mother and a great way to use oral history and personal archives into a compelling story. We did an interview with Hanan last year and she told us how, as a journalist, she had worked on profiles of accomplished women in different fields in Lebanon. And how her mother said something along the lines of “all these women you write about had good families and access, but I came from a poor background, and I struggled, and I wasn't taught to read and write. You have to write about me, and I’m dying to tell my story.” The story and the events are amazing. The mother is such a great storyteller, and so witty with words. But also, the way in which the story reveals the social and political context in which she lived was very interesting to read.

Audre Lorde’s Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982)

Talah Hassan, oral history and storytelling coordinator at KW, chose Audre Lorde’s “biomythography,” an innovative genre merging biography and myth that the black feminist poet experimented in Zami.

TH: This was the first book of Audre Lorde's that I read cover to cover. Previously I had read her essays while doing graduate work in university. I really like this book because of the biographical elements and the poetry together, the many themes explored that beautifully speak to each other. Friendship, sexuality, motherhood, but also history, race, and slavery, all of equal importance and inseparable. We talk about this inseparability usually in theoretical terms as intersectionality. But here in this book you see them woven into someone’s story and life, poetically and with an honesty that is refreshing, beyond the intersectionality of identities and into the intersections of life's experiences. For instance, you see how family relationships impact her relationships with friends. The layers of history are there, enmeshed, and tensions explored.

Elizabeth Thompson’s Colonial Citizens: Republican Rights, Paternal Privilege, and Gender in French Syria and Lebanon (1999)

Elizabeth Thompson is a historian of social movements and liberal constitutionalism in the region. Colonial Citizens is a foundational text in gender studies from mandate Lebanon. The Publisher describes it as “a major contribution to the social construction of gender in nationalist and postcolonial discourse. Returning workers, low-ranking religious figures, and most of all, women to the narrative history of the region—figures usually omitted.” This is Deema’s last pick.

DK: I choose Elizabeth Thomson’s book because of the history. This book had stories I hadn't encountered anywhere else about certain protests or certain discourses in the country. I must re-read it, but I remember it being quite an impressive study of 1940s Lebanon, gender and women’s rights at the time, and [it] got me more curious about the [mandate] period.

Visit the Feminist Library at Castoon (Pain d’or) Building, 3rd floor, General Chehab Street, Furn El Chebbak, Beirut, Lebanon. Open Monday to Thursday. With the evolving COVID-19 situation, calling beforehand is recommended.