Between Kafala and Governmental Neglect: How Domestic Workers Are Left to Starve During a Global Pandemic

Day 194: Monday, April 27, 2020

With the onset of the pandemic since February in Lebanon, domestic workers have experienced a steep deterioration in their livelihoods. Laid off or forced into unpaid labor since the start of the economic crisis, they now face previously unknown challenges with the coronavirus: starvation and homelessness. Since neither the Lebanese government nor their own are looking to assist them, they are under siege at the mercy of a harmful system.

Of course this predicament predates the outbreak of the coronavirus. In a previous article for The Public Source, I wrote about the endless misery suffered by domestic workers following the economic meltdown that resulted in protests across Lebanon since October 17. I clarified why the potential fruits of revolution were unlikely to trickle down to Lebanon’s most marginalized community, and that the economic crisis has exacerbated their already precarious legal and living conditions. With the global pandemic the situation is more desperate than ever.

The root cause of their affliction continues to be “kafala” or sponsorship system. The system literally puts a domestic worker’s legal status in the hands of an often unpredictable, violent, and abusive employer, while excluding her from the limited protections of the labor law. Kafala also gives the employer carte blanche to inflict all sorts of horrible deeds against her, confiscate her passport and, worse of all, enslave us. I have always described kafala as a prison sentence for two years and three months, the duration of a domestic worker’s contract, without a crime. Many promises by high-ranking officials, including former Labor Minister Camille Abousleiman, were vocalized but remained empty.

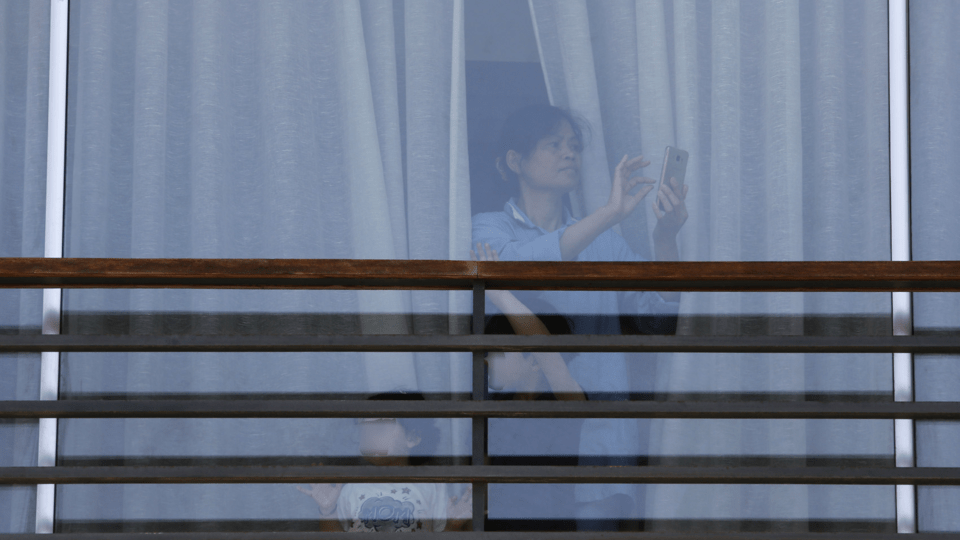

In 2017, I founded Egna Legna Besidet, which is Amharic for “from us migrants for us migrants,” in Beirut with fellow Ethiopian domestic workers. We lobby for the rights of domestic workers and raise awareness about the dangers of working in Lebanon as a migrant domestic worker. Since the Lebanese government announced a nationwide lockdown following the spread of the coronavirus, domestic workers, many of whom have gone months without pay following the economic collapse, have been forced to spend their days with agitated, anxious and bored employers. Our organization is receiving calls and Facebook messages from Ethiopian domestic workers all across Lebanon that paint a picture of life on lockdown with their employers.

I have always described kafala as a prison sentence for two years and three months, the duration of a domestic worker’s contract, without a crime.“I am afraid to even cough,” one woman wrote. “I sneezed once and my madame [the employer] stared at me with horror. I’ll be kicked out into the streets if they think I caught the virus, and so I run to another room when I feel the need to sneeze or cough.” Another woman told us that she had a sore throat, but was too afraid to tell her employer she might be getting ill. Moreover, women report being overworked because their employers are at home all day. If previously they were able to catch their breath when their employers were at work, this has become impossible. In more severe cases, women narrated tales of beatings, of being kicked out of the house by irritable employers, left to fend for themselves in the streets. Racism in a new guise has also become prevalent, as some employers believe that Africans are more susceptible to catching the virus. We heard from women who tell us their employers force them to wear gloves and masks at all times, and we have seen pictures that prove this incredible ignorance.

If domestic workers were previously able to at least plead to be released or sent back to their employment agencies, today this option is lost to them. There are virtually no shelters to seek, as many NGOs reduced their operations following the lockdown. Employment agencies are open, but many are refusing to take in their own recruits, supposedly out of fear of spreading the disease. Embassies are also closed. For the countless women toiling indefinitely for their employers, there is nowhere to go, even if they managed to escape. Leaving these homes now is not only unthinkable but also dangerous, as they risk both arrest for breaking the lockdown and contracting the virus with little possibility of medical help.

Indeed, the emotional toll has been immense. One woman has already attempted to take her own life after her employer cut her off from the rest of the world, leaving her unaware even of the revolution and pandemic. She survived. While hospitalized, she was given phone access by nurses for the first time in six months, which is how she got in touch with us. What she needs is to get out of that terrible house, but this is not an option for the time being. For now, we managed to stay in communication and she appears to be doing better.

If domestic workers were previously able to at least plead to be released or sent back to their employment agencies, today this option is lost to them. There are virtually no shelters to seek, as many NGOs reduced their operations following the lockdown. Employment agencies are open, but many are refusing to take in their own recruits, supposedly out of fear of spreading the disease.Unlike the contract workers who live in the homes of their employers, survival for “freelancers,” who like me fled abuse or sexual assault and are no more confined against their will, has become an insurmountable challenge. They have had to find a place to live, pay rent and lay low not to be caught by immigration officials. From the moment we flee our employers, our residency status becomes void since working without a sponsor is illegal. While technically free, most of these workers have been laid off and have no income following the pandemic. No employment means that affording basics such as rent and food is no longer guaranteed. Being undocumented makes them doubly vulnerable and the airport closure makes returning home impossible.

Single mothers who freelance are the most vulnerable. Many were raped and got pregnant, while others were tricked into thinking they had found a partner only to be abandoned shortly after. These women shoulder the burden of caring for unplanned children while living in a society that shames them. Feeding their children has become their daily angst. There are mothers contemplating giving up their infants for adoption. While others scrounge for bits and pieces to ensure survival into the next day. Egna Legna Besidet has launched an online fundraising campaign and we have distributed food prioritizing single mothers and workers with urgent medical needs. But our resources are limited and governmental support is lacking, even as the situation is taking a sharp downturn. A mother who was laid off early in the revolution tells us that she used her remaining savings to cover rent and food basics for her toddler. But now, left with no money left for milk and food, her breast has dried up, leaving her unable to sustain her daughter. At her wit's end, she started boiling rice using the remaining water she had as a substitute for her baby’s milk. This is one of many stories that keep us sleepless at night.

The Ethiopian consulate has been a great disappointment. It has shut its doors and hasn’t launched an emergency response, even for freelancers needing food and rent support in the face of merciless landlords who want to evict them. Workers are caught between a rock and a hard place, starvation, and eviction. There are several other Ethiopian-led organizations and community groups, like Egna Legna Besidet, using limited resources to distribute food basics. The collective effort is heartwarming, but far from sufficient. In times like these, the Ethiopian government must step up. Ethiopian citizens have been pleading for evacuation from Lebanon for months, but merely allocating resources to provide food for those at risk of starvation is a vital starting point. While the Ethiopian consulate advertises the work of organizations like ours, it has not, as of now, spent a single penny to support its expats.

The Ethiopian consulate has been a great disappointment. It has shut its doors and hasn’t launched an emergency response, even for freelancers needing food and rent support in the face of merciless landlords who want to evict them. Workers are caught between a rock and a hard place, starvation, and eviction.I got to see this broken system first hand. In Ethiopia, the office of the Foreign Ministry’s Director General for Middle East Affairs, Shamebo Fitamo, supposedly oversees our living conditions in Lebanon. When international news agency Reuters questioned Fitamo about the Ethiopian government’s response toward its citizens in Lebanon, he claimed that the embassy was working with the community to distribute food, and then added, “if repatriation is needed, we’re preparing for that also.” Of course, there is not a grain of truth to this, and not one organization or community group has received food or financial support from the consulate. In our regular communication with the consulate, “financially stretched thin” is a recurring refrain. There is no taxpayer-funded initiative here. We are on our own. And evacuations are urgent now, there is no questioning it, but the Ethiopian government is intentionally downplaying the disaster we are facing. We should have been evacuated at the start of the economic crisis last year.

Fitamo didn’t take it warmly that I was quoted contradicting him in the same Reuters article. He hastened to write on his Twitter page that I was “sitting in Canada, misleading people” and that I had to “leave things to a government that knew what it was doing.” But I’m not misleading anyone. My work has me coordinating food distributions in Lebanon while answering our social media hotlines and listening to the most vulnerable and broken people plead for help. At times, it feels like I’m still in Lebanon. I am more than acquainted with the worst the country has to offer where I spent nearly a decade working as a domestic worker, two years of which without a day off, physically abused, and underfed. I am all too aware of the hunger and desperation my compatriots experience. The truth is we are undervalued as citizens. In another tweet, Fitamo stated that repatriating Ethiopian domestic workers from Lebanon was out of the question because they could carry the virus to Ethiopia and endanger its population of 110 million. We are second-class citizens, merely an afterthought.

Once again, domestic workers — regardless of nationality — have been abandoned to their fates. But it shouldn’t be that way. These women used to send remittances and contribute to their countries’ GDPs. And yet, most have received no assistance from their governments in a time of emergency. I will continue to call upon all countries with citizens working as domestic workers in Lebanon to own up to their responsibilities. Shutting the doors of their embassies in times like these is immoral. Open your doors, divert funds from other meaningless ventures, and invest in the food and medical supplies your citizen workers desperately need. I also call upon the Lebanese government to allow undocumented domestic workers to leave Lebanon, if they want to, without paying hefty immigration fines. Most have been out of jobs for five, six, some even nine months. Some have had no choice, but to beg on the streets to survive. There’s nothing left to extort from these women. Like everyone else in Lebanon we are all hoping this is the worst of it.