Paradise Lost? The Myth of Lebanon’s Golden Era

“To a considerable degree, the dream of making Lebanon the Switzerland of the Middle East has been realized.”

So concludes a 1958 article by an American author who, according to his byline, “worked for financial institutions in Beirut between 1953 and 1957.” The Swiss dream in this instance referred to Lebanon’s economic boom in the first half of the 1950s – which the author credits wholly to free-market policies and the deliberate absence of socioeconomic development planning by Lebanese governments.

In October 1982, only months after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, ARAMCO World Magazine published an issue titled “Paradise Lost: A Eulogy for Lebanon,” filled with articles written by Westerners who had experienced the Lebanon of the pre-war era. Together they convey a sense of a lost world, lamenting the passing of an age of innocence, prosperity, and abundance.

Today, we see similar tropes, disseminated by Lebanon's ruling parties as well as its regular citizens. Whose social media feed is free from nostalgia-filled posts and images of pre-war Lebanon as a lost idyllic haven?

But as is often the case: All that glitters is not gold.

If we zoom out of the familiar glitzy photographs of the glamorous lifestyles of the few, a darker picture emerges. One where Lebanon’s “free market” brought wide-scale misery to the population, with only a small minority enjoying its fruits.

The imaginary of a golden pre-war Lebanon goes beyond nostalgia for a past that never existed. It does work in the present and towards the future, actively and insidiously working to sustain the myth that Lebanon can only thrive as a free-market economy with quasi-inexistent state intervention.

The imaginary of a golden pre-war Lebanon goes beyond nostalgia for a past that never existed. It does work in the present and towards the future, actively and insidiously working to sustain the myth that Lebanon can only thrive as a free-market economy with quasi-inexistent state intervention.

The Real 1950s Lebanon

In 1959, then-president Fuad Chehab commissioned IRFED, a French NGO, to carry out an extensive study of the country’s socioeconomic conditions in major cities and eighty rural areas. Unlike his predecessors and most of his contemporaries, Chehab came from a military background, which had exposed him to the underdevelopment and unequal development across the country. He conceived of the IRFED study as a springboard for developmental planning.

IRFED’s findings, submitted to the government in May 1961 and employing over 140 development indicators, are a damning indictment of the economic policies of independent Lebanon’s first governments.

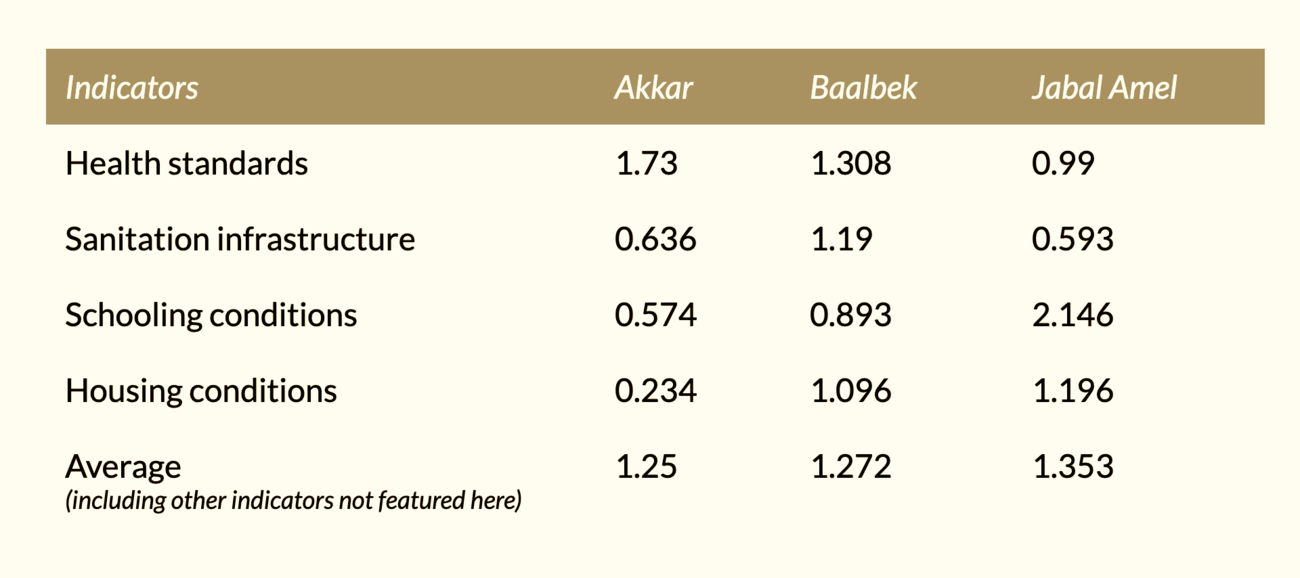

Socioeconomic indicators for areas in Akkar, Baalbek, and Jabal Amel in 1960. The scores range from 0 (no development) to 4 (high level of development). Source: IRFED, "Le Liban au Tournant," 1963.

The most extreme underdevelopment was found in the regions of Akkar, Baalbek, and Jabal Amel, whose residents suffered from very poor infrastructure, education, and public health services. The table above showcases the starkest figures in the report (but other indicators do not fare much better).

Children in Akkar on their way to fill up water from a well, July 1967. (Photo courtesy of Lebanon Archives/أرشيف لبنان).

Even in Beirut, the crown jewel of Lebanon’s “golden era," there were cracks.

At the time the IRFED study was conducted, the “miserable suburbs of Beirut” (as some refer to the neighborhoods south of the capital) were still relatively small. Fifteen years later, on the eve of the civil war, they had come to house thousands of Palestinian refugees, Syrian workers, and Lebanese migrants escaping extreme deprivation and feudalistic subservience in rural hometowns controlled by large landowners and major agro-industrial firms.

Yet in 1960, the living conditions in other Beiruti neighborhoods were truly appalling.

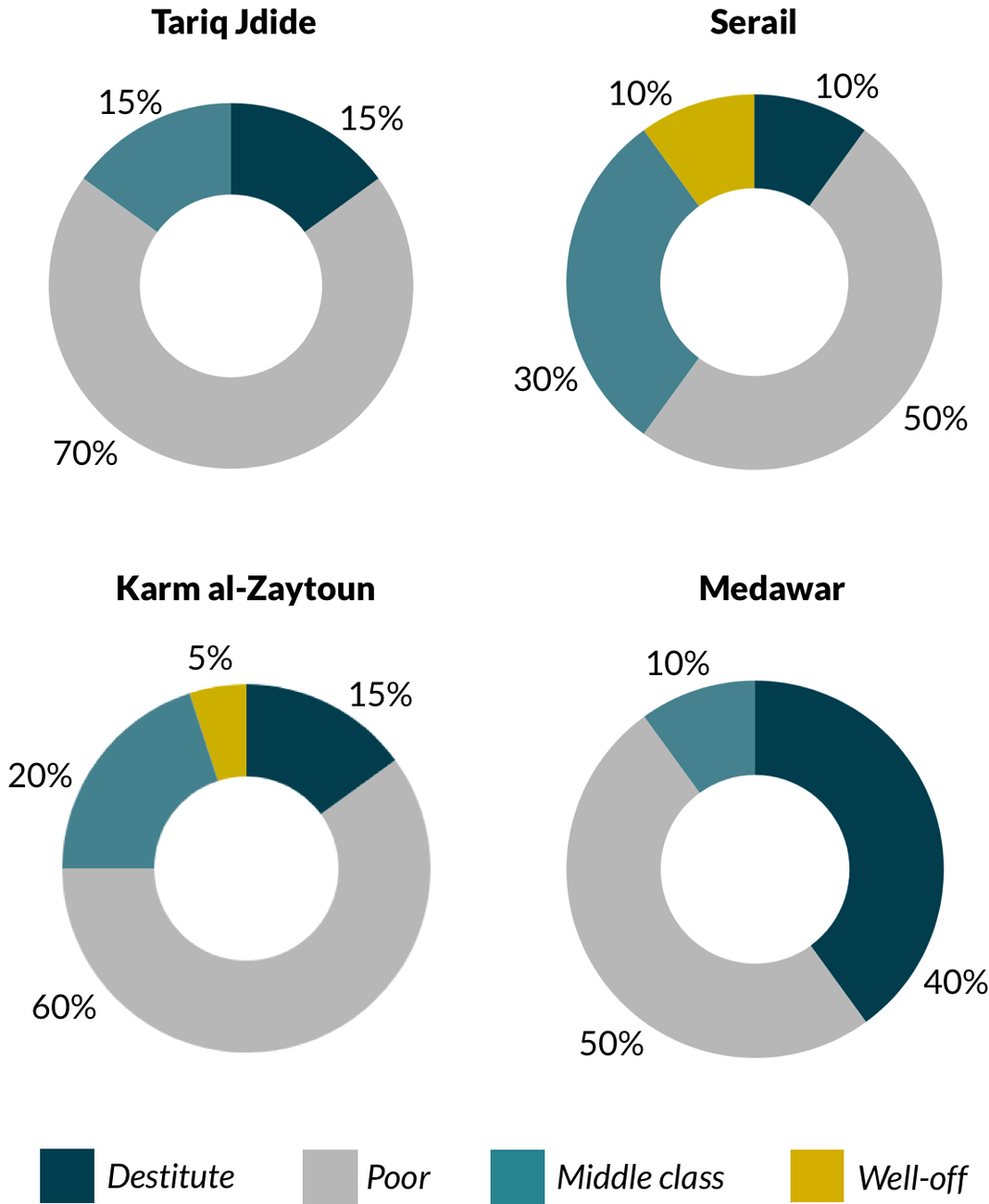

The industrial area of Medawar, made up largely of Armenian-Lebanese communities, Syrian workers, and rural migrants obtained an average developmental score of 1 out of 4. Housing consisted mainly of overcrowded makeshift homes, few households had access to electricity, and telecommunications and sanitation infrastructures were virtually nonexistent. Around 90 percent of the neighborhoods’ inhabitants were labeled in the report as “misereuse” (destitute) and “classes populaires” (poor), meaning they were earning below 1,200 or 2,500 L.L. annually, respectively (or roughly between $3,600 and $7,500, as per the exchange rate in the early 1960s). In other words, their incomes were barely enough for subsistence.

The situation was not much better in Tariq Jdide, where 85 percent of residents made less than 2,500 L.L. and lived in overcrowded dwellings with primitive sanitation infrastructure and overcrowded, poorly equipped schools.

In Karm al-Zaytoun, few completed primary or secondary school and cocaine and heroin were widespread, according to the report.

IRFED’s findings, submitted to the government in May 1961 and employing over 140 development indicators, are a damning indictment of the economic policies of independent Lebanon’s first governments.In centric Serail, there were no public schools and residents lived in overcrowded slum-like dwellings on garbage-filled streets, with the detrimental public health effects that entailed.

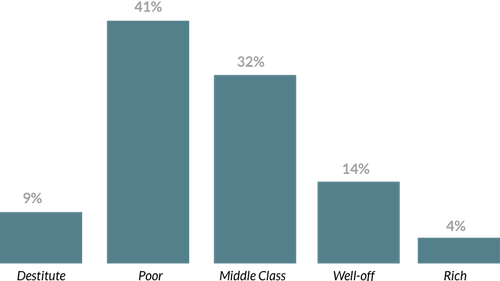

Geographic inequalities were matched by income inequalities between households. According to IRFED’s research, half of all households in Lebanon lived in poverty or destitution in 1960.

Who then benefited from the bounties of Lebanon’s gilded age?

Household Income Distribution in Lebanon in 1960-1961

Destitute households were earning below L.L. 1,200 per year; poor households between L.L. 1,201 and 2,500; middle class households between L.L. 2,501 and 5,000; well-off households between L.L. 2,501 and 15,000; rich households above L.L. 15,000. In 1964, 1 Lebanese Lira was worth $3.1, as per the Central Bank. Source: IRFED, "Besoins et Possibilités de Développement du Liban. Étude Préliminaire: Tome 1," 1960-1961.

Whose Golden Era?

Lebanon’s commitment to free market ideology was enshrined at independence, thanks in large part to the New Phoenicians, a group of like-minded, politically-connected bankers and businessmen who managed to turn free market ideas into official government policy.

The New Phoenicians envisioned a country built on the services and financial sectors, where agriculture and industry would be an afterthought; they paved the road for a Lebanese state lacking socioeconomic development plans for these productive sectors, kept afloat by workers toiling under harsh and exploitative conditions.

The St. George, a landmark hotel inaugurated in 1934 and owned by French investors until the late 1950s, where, according to George Corm, “[i]f you were part of the affluent society, it was the place where people would come to have a drink.” May 2, 1965. (Indiana University Archives, Charles Cushman Collection)

Their worldview is best exemplified in the writings of Michel Chiha, a prominent member of the cohort who had participated in molding the 1926 Constitution, and brother-in-law of Lebanon’s first post-independence president Bechara al-Khoury. Chiha argued that Lebanon was made for the free market: The country’s geography, the entrepreneurial ethos running through its people since ancient times, its sectarian heterogeneity — all demanded the adoption of free market policies, starting with free trade and movement of capital.

Foreign exchange controls were reduced in November 1948 and eventually eliminated in 1952, allowing Lebanese capital to “move freely throughout the world.”

According to IRFED’s research, half of all households in Lebanon lived in poverty or destitution in 1960.

Global capital was also welcomed into Lebanon, mediated through a select few. Rival feudal lords, businessmen and merchants in the services and finance sectors – either through public office or in collusion with holders of public office – turned Lebanon into a conduit for the import of Western capital and commodities, and monopolized major key industries.

By 1974, 13 families controlled 47 percent of total industrial capital, 30 percent of total bank assets and 24 percent of total capital in commerce, agriculture and service companies; a mere four politically-connected firms were responsible for importing two-thirds of all commodities from the West.

The considerable growth in the number of government officials under Bechara al-Khoury – from under 6,000 in 1947 to 14,800 in 1953 – served to stack the Lebanese public administration with cronies who used their office to further the business interests of a few, through lucrative public works contracts.

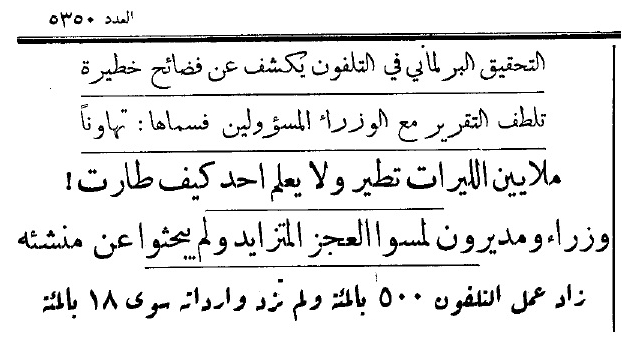

The corruption scandal of the Telephones Authority in the early 1950s is a prominent example of the kind of cronyism that was all too rife during al-Khoury’s presidency. According to a parliamentary report published in Annahar in 1953, between 1947 and 1951 the entity went from being a well-functioning, lucrative public corporation with 380 civil servants to one with 2,200 civil servants, dwindling revenues, and in deficit. The report specifies that the new employees were imposed by ministers, parliamentarians, and feudal lords — but refrains from naming them. The new staff did little other than earn a paycheck at the end of the month, forcing the Authority to take a loan from a local bank to cover its deficit.

On May 30, 1953, Annahar published a parliamentary report on a corruption scandal in the Telephones Authority.

Thwarted Reforms

In 1958, a brief civil war rooted in class antagonism erupted, as left-leaning paramilitary groups with sympathies to Egypt’s president Jamal ʿAbd al-Nasir and the nascent United Arab Republic waged an armed struggle against oligarchic president Camille Chamoun and his government. In September of that year, following a military stalemate due to the arrival of US marines summoned by Chamoun, army commander Fuad Chehab assumed the presidency.

Acutely aware of socioeconomic disparities, Chehab’s mandate was characterized by key reforms within the public administration as well as modest attempts at bridging socio economic cleavages, such as establishing the National Social Security Fund.

By 1974, 13 families controlled 47 percent of total industrial capital, 30 percent of total bank assets and 24 percent of total capital in commerce, agriculture and service companies; a mere four politically-connected firms were responsible for importing two-thirds of all commodities from the West.But the reform oriented Chehabists became increasingly repressive, particularly after the failed coup attempt by the Syrian Social Nationalist Party in December 1961. And when Chehab’s term ended in 1964, reforms slowed down significantly.

As geopolitical tensions grew, feudal lords — or “cheese eaters,” as Chehab called them in reference to their devouring of the public sector — managed to oust Chehabists from office in 1970.

The feudalistic new president and prime minister, Suleiman Frangieh and Saeb Salam, were compelled to form a government that would supposedly respond to growing pressure from below. The result was the anomalous “youth government” (houkoumat al-shabab) made up of unknown young technocrats who pledged to enact long-awaited wide-scale reforms.

Their efforts were thwarted before they began by parliament and the merchant class.

Such was the case of Decree 1943 in 1971, through which finance minister Elias Saba tried to raise customs dues on over 500 imported commodities — including luxury items such as expensive cars and goods that had locally produced equivalents — in order to protect local industry and employ additional government revenue towards socio economic development.

A 10-day strike by merchants and shopkeepers in Beirut, tacitly supported by the oligarchy, killed the decree under the absurd reasoning it would harm tourism and the middle class.

Similarly, health minister Dr. Emile Bitar lost his bitter struggle against pharmaceutical importers to make healthcare more affordable and accessible.

A handful of pharmacies and pharmaceutical importers, all tied to the oligarchy, monopolized the market by importing and selling only the most expensive drugs for astronomical profits. This cartel had managed to stunt any substantial growth of the local pharmaceutical industry by lobbying for high tariffs on equipment needed for the local producers.

Bitar attempted to place a ceiling on their profits, diversify the type of medicines imported, and support the local pharmaceutical industry. Pharmacies and importers accused him of destroying Lebanon’s free market economy and creating medicine shortages.

Ultimately, with little support from parliament and from his colleagues in the Council of Ministers, Bitar resigned in protest in December 1971.

On the eve of the civil war, top-down attempts to break some of the oligarchic hold had been thwarted.

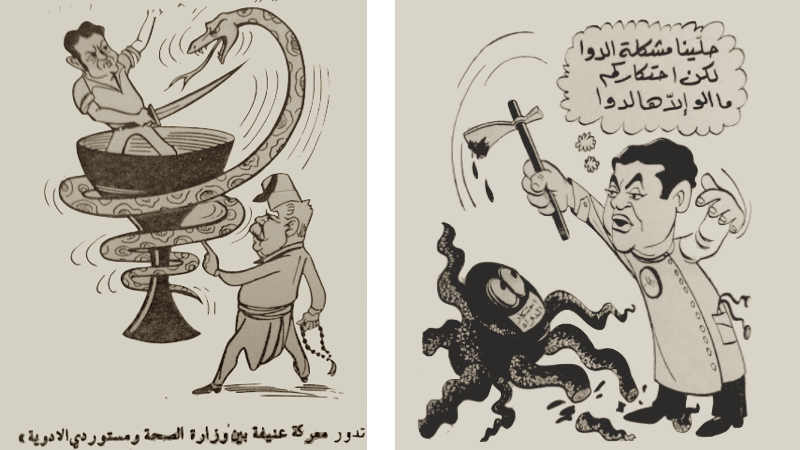

Cartoons published in the local press in the early 1970s depicting health minister Dr. Emile Bitar fighting the pharmaceutical cartel, symbolized by a snake and an octopus. (Courtesy of Karim Emile Bitar and Phares Zoghby Library and Archives, Kornet Chehwan).

The Erasure of Socioeconomic Struggle

Imaginary narratives of a prosperous pre-war Lebanon ignore not only its extreme socioeconomic inequalities, but also erase the widespread discontent and class struggle of the time.

Episodes of labor unrest demanding living wages, basic social protections, a fair labor law, and an end to workers’ exploitation — such as the 1946 strike in the state-owned tobacco monopoly or the 1972 strike in the Gandour factory — are rarely if ever mentioned.

The widespread student agitations of the 1960s and early 70s against soaring inflation and socioeconomic inequalities, which were often framed in solidarity with the Palestinian cause, when acknowledged, are seen as a nuisance or as dangerously naive utopianism.

The workers and students injured or killed by the state security apparatus have no place in the golden era narrative.

In April 1976, a year after the civil war started, warlord and former president Camille Chamoun bluntly told a reporter:“[Lebanon is] a country of free enterprise and Lebanon has been built and become [...] prosperous thanks to private initiative.” He added: “Unfortunately, there are two kinds of people in Lebanon: People who want to work and make money, and people who want to make money without working.”

Such a statement is unsurprising, coming from a leading member of Lebanon’s oligarchy. If only any of it were true.