Homage to the Honest Soldiers

“Who Remembers the Armenians?”

I remember them

And I ride the nightmare bus with them

each night

and my coffee, this morning

I’m drinking it with them

You, murderer—

Who remembers you?

Najwan Darwish

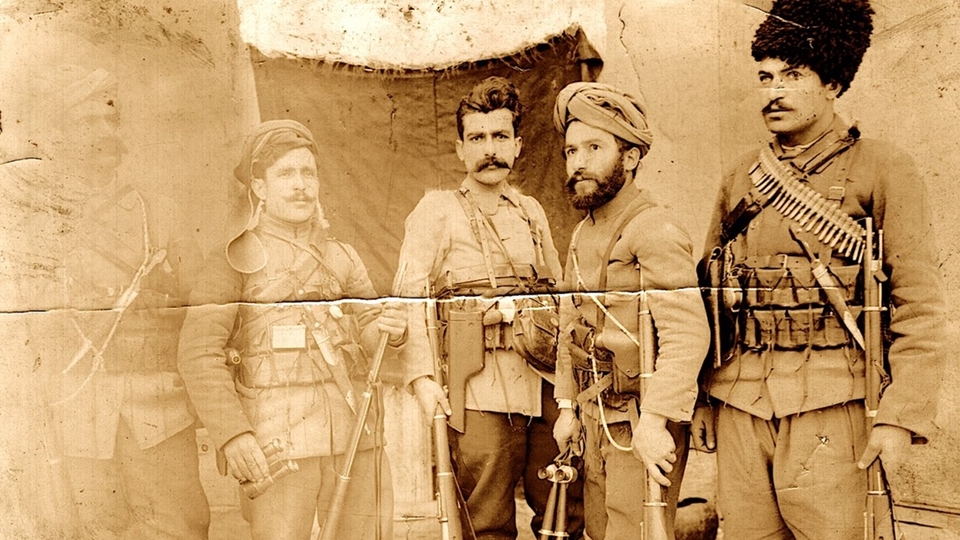

The song “Մենք Անկեղծ Զինուոր Ենք,” transliterated as “Menk Angueghdz Zinvor Enk,” roughly translates to “We Are Honest Soldiers.” Khatchadour Kevorkian (1867-1921), better known as Fahrat the Troubadour, wrote this Armenian revolutionary song sometime after 1897 to praise the Khanasor Expedition. That year, an Armenian fedayi brigade launched a retaliatory expedition against the Kurdish Mazrik tribe, killing their fighting men for carrying out, alongside the Ottoman forces, the Armenian massacres (1894-97), which orphaned an estimated 50,000 children in 1895 alone.

Constantinople, a decade or two later, Levon Hampartzoumian and two accompanying violinists record the song, perhaps for the second time, in the 1910s, a long decade full of historical happenings, or in the early 1920s. Leading up to that was the 1908 Ottoman Revolution, a joint effort between progressive Turks, Armenians, and other minorities, which ended the absolute monarchy and reinstated the Constitution. Then, in 1913, the revolution gave way to a coup d’état by high-ranking officers and ministers from the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), originally composed of various political groups that participated in the revolution. The CUP quickly became a dictatorship driven by the mission to homogenize the nation. In 1915, it gave the order for the Armenian genocide. “We Are Honest Soldiers” could have been recorded as a call to arms in the context of genocide, or its aftermath, harkening back to the Khanasor expedition of 1897 and the Zeytun rebellion of 1895-6 against Ottoman rule.

“The enemy called us fedayi,” begins the second verse, “and we lived up to the name.” Who was the enemy in 1897? Is it the same enemy that the performers and the listeners thought about, nearly two decades later when Levon sang? Is it the Kurdish paramilitary, the Ottoman military deployed to crush national liberation movements from Greece, in the nineteenth century, to the Arab Revolt in the final years of the empire–or, the CUP? Whether the enemy is one or many, this enemy bestowed upon the Armenian revolutionaries the Arabic term for “those who sacrifice themselves.”

“We Are Honest Soldiers” declares the willingness to sacrifice the self to protect the Armenians of Anatolia, and pays homage to the Feda’iyeen of the region, across the ages — ‘honest soldiers,’ in their own right.

The term “fedayeen” may have emerged between the 11th and 13th centuries about the order of Assassins within the Nizari-Ismaili branch of Islam. As for voluntary brigades in Ottoman Armenia, they may have also adopted the term from the constitutionalists who led the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-6 in Iran against the monarchy. Some members of the Armenian resistance against the Ottoman Empire’s repressive policies against Armenians were also actively involved in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution. Notable among them was Stepan Zorian, known by his nom de guerre, Rostom, who co-founded the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) — الاتحاد الثوري الأرمني / Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցութիւն — in Tbilisi in 1890 and managed their journal, Troshag (Դրօշակ, meaning Flag), in Geneva.

“We Are Honest Soldiers” declares the willingness to sacrifice the self for the cause — in this case, to protect the Armenian communities of Anatolia from intimidation, pogroms, and, eventually, the genocidal policies of the CUP regime. “We lived up to the name” pays homage to the fedayeen of the region across the ages — ‘honest soldiers,’ in their own right.

During the First World War, while the Arab Revolt was in progress and the Armenian Genocide was well underway, British forces began to support Arab nationalist revolutionaries. In the aftermath of the war, the French army, alongside Armenian volunteers, assumed control over the ethnically cleansed Armenian territories of Southern Anatolia. But soon after, both the Arabs and the Armenians were betrayed by their Western allies. The United Kingdom decided to hand Palestine over to Zionist settlers. At the same time, the French withdrew from Southern Anatolia in 1920-1921, abandoning the Armenians to Kemal Ataturk’s republic, an ethnostate born out of genocide.

“Feda’iyeen” was once more adopted by Arab freedom fighters, particularly Palestinian militants, resisting settler colonialism, and feda’i work intensified in the 1960s and 70s. Like the Turkish ethno-state, the Zionist project depended on ethnic cleansing.

Fedayi resurfaced in the late 1980s, as self-organized militants from the ARF embraced it, the Social Democrat Hunchakian Party, and the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia, among others. This time, the term symbolized the readiness to sacrifice for the freedom and right to self-determination of the Armenians of Artsakh — the indigenous name of Nagorno-Karabakh. The self-defense initiatives were in the context of pogroms targeting Armenian communities across Azerbaijan in 1988, then the 1991 democratic referendum calling for the proclamation of Artsakh as a sovereign state, which was rejected by Azerbaijani authorities.

Embraced by self-organized militants from the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, “fedayi” resurfaced in the late 1980s to symbolize the readiness to sacrifice for the freedom and right to self-determination of the Armenians of Artsakh — the indigenous name of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Based on oral history accounts from members of my family, who, at the time, were closely tied to the ARF, the song, “Մենք Անկեղծ Զինուոր Ենք,” resurfaced again, nearly seven decades after Levon Hampartzoumian’s recording. It was sung by ARF militants and supporters, and was heard over the radio waves of the Armenian diaspora, notably Voice of Van, in Beirut, which still airs at 94.7 FM. The First Nagorno-Karabakh War led to a temporary victory, enabling the Armenians of Artsakh to maintain autonomy for approximately three decades, from January 1992 to September 2022, while the Palestinians witnessed ongoing encroachments on their lands and the ethnic cleansing of their people.

Fast-forward to 2021, then 2023, and Azerbaijan ethnically cleanses Artsakh in two new invasions, the so-called Second Karabakh War. Many states empowered Azerbaijan to complete the takeover: The second largest NATO army, the Turkish military, trained its forces, while Israel backed them with high-tech weapons, raining fire from the sky, paid with petro-dollars from Azerbaijan's own oil and gas sales to Europe.

In return, by the third week of October 2023, one million barrels of Azerbaijani oil went to Israel to feed the war machine in Gaza.

Azerbaijan is no exception in buying Israeli military and surveillance equipment. Israel is, after all, the 10th largest arms dealer globally, selling weapons to an estimated 130 countries, including military juntas and fascist police states in Africa, Eurasia, and Latin America. Azerbaijan had to pay good money for the Israeli weapons, as they are “battle-tested” every year or two in Gaza. The Israeli arms and tech industries treat Palestinians like human lab subjects, testing such military technologies as drones, surveillance, smart fences, experimental bombs, and AI-controlled machine guns to be “certified” before the world could buy them.

ARF militants and supporters sang “We Are Honest Soldiers” in the 1980s, and the song was heard over the radio waves of the Armenian diaspora, reaching the Voice of Van in Beirut, at 94.7 FM.

The 2023 full-scale Azerbaijani assault on Artsakh, powered by Israeli high-tech death machines, ethnically cleansed the autonomous enclave of 120,000 indigenous Armenians who had been living there for millennia.

More and more, it seems that the ethnic cleansing of the 120,000 Armenians of Artsakh was the dress rehearsal for the ethnic cleansing of 2.3 million Gazans. However, to displace a much larger population in Palestine, Israel has carried out a much more brutal carpet bombing campaign that the occupation likes to sadistically describe as “mowing the grass,” a phrase coined in a 2014 paper from the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies.

“Mowing the grass,” something one does recurrently in landscaping to keep the lawn in order, is a figure of speech that the Zionist military casually uses for recurrently killing Palestinians every one or two years. The murderous expression, spoken often with cynical laughter, creates an analogy between blades routinely cutting grass and blades shooting out of the Hellfire R9X, for example, better known as the “ninja bomb,” cutting through Palestinian bodies.

That ‘grass’ is Gaza, specifically 2.3 million Palestinians, half of whom are children, and everything that makes life in Gaza possible: their homes, schools, hospitals, cultural institutions, and bakeries. “Mowing the grass” means razing everything to the ground, a genocidal policy premised on the unwillingness to see anything but grass to cut with a razor, or raze to the ground.

In the current war on Gaza, Israel’s actions went well beyond regular war crimes toward crimes against humanity and from slow ethnic cleansing to accelerated genocide. It is clear by now that Israel has two options in mind for the Gazans: death in what has turned into a concentration camp or displacement to the Sinai Desert – if Egypt collaborates.

The 2023 full-scale Azerbaijani assault on Artsakh, powered by Israeli high-tech death machines, ethnically cleansed the autonomous enclave of 120,000 indigenous Armenians who had been living there for millennia.

Historian Ronald G. Suny published They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else in 2015 for the centennial of the Armenian Genocide. The title of the book evokes the Armenians’ forced death marches, ordered by the central government in Constantinople and implemented by local Turkish officials, in the deserts of Syria — a story of mass death through massacres, starvation, and disease that takes on a contemporary layer of meaning with the violent threat of displacements for Gazans.

Drawing a comparison between the establishment of the homogenized Turkish nation-state with US, Australian, and Zionist settler-colonial states, Suny argues that the subjugation and displacement of indigenous populations were part of the process to establish the respective nations, something that nation-states contest and deny to maintain legitimacy.

Azerbaijan has been implementing a similar policy since the dissolution of the USSR. The subjugation of the Armenians begins at school, with textbooks filled with racist stereotypes, and continues on TV, with state media inciting hatred and violence. Armenians are not the only ethnic minorities perceived as a security threat to Azerbaijan — discrimination also extends to Talyshon and Lezgins. They are almost excluded from the history curriculum and face intimidation by local authorities, under the watchful eye of the state, so they can no longer teach their languages. Besides ethnic cleansing, these unstated state policies support the homogenization project in Azerbaijan.

Suny concludes his text on this somewhat hopeful note.

Coming to terms with that history… can have the salutary effect of questioning continued policies of ethnic homogenization and refusal to recognize the claims and rights of those peoples, minorities, or diasporas — Aborigines, Native Americans, Kurds, Palestinians, Assyrians, or Armenians — who refuse to disappear.

The term “Feda’iyeen” persists in armed struggle, bodies on the line, solidarity sieges, journalism under fire, and civil disobedience. The spirit of the fedayeen, along with decades of Palestinian resistance, persists in the thick of Israeli settler-colonial violence and its imperial tutelage. As repression becomes increasingly mechanized and high-tech, the resistance turns analog, reverting to more traditional methods, to its origins, to individuals in civilian attire confronting tanks at ground zero, evading missile strikes and aerial surveillance. The analog reversion harkens back to the image of a child, Faris Odeh, fearlessly hurling rocks at occupation forces, echoing, perhaps ironically, the tale of a young David defeating the giant Goliath with a slingshot.