“Victory Over My Jailer”: The Afterlife of Revolutionary Walid Daqqa’s Steadfast Love

Introduction by Christina Cavalcanti

Walid Daqqa (July 18, 1961 — April 7, 2024), born in the occupied town of Baqa al-Gharbiyye in northern Palestine, was a Palestinian revolutionary leader, thinker, and prolific writer who resisted against the Israeli settler colony from within its prisons, where he fought fierce battles for 38 years of his life, until his assassination through severe medical negligence at the age of 62. At the time of his death, he was the longest-serving Palestinian political prisoner.

In 1986, Daqqa and comrades from the Palestinian resistance were arrested and given life sentences after carrying out a resistance operation targeting an Israeli occupation soldier — charges Daqqa continuously denied. Daqqa’s sentence was reduced to 37 years in 2012, but he was denied release on March 24, 2023. In 2018, an Israeli military court added two more years to his sentence, allegedly for smuggling cell phones into the prison. Despite calls for his early, urgent release because Daqqa was terminally ill and had completed his sentence, his March 24, 2025 release date remained fixed. Throughout his unjust imprisonment, Daqqa was physically and psychologically tortured, and was refused family visitation rights and denied medical care — even on his deathbed — in spite of a leukemia diagnosis in 2015 and a myelofibrosis diagnosis in 2022.

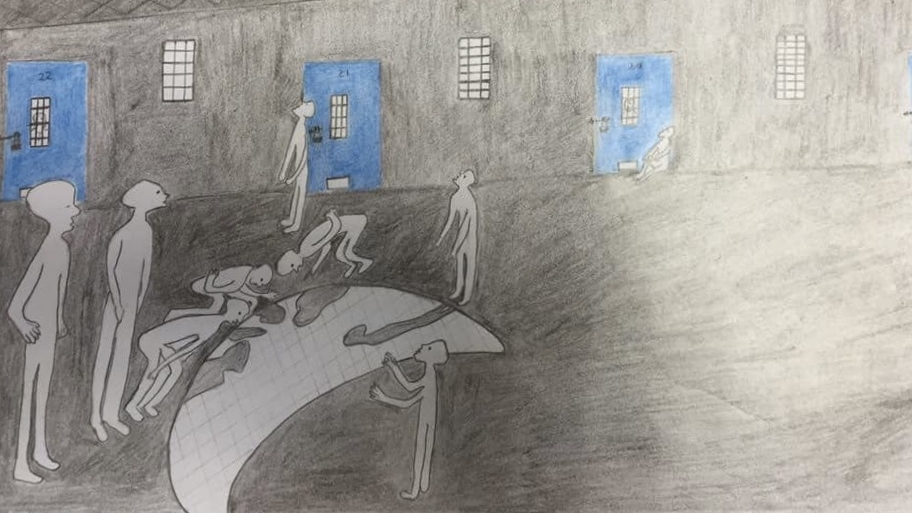

The brutality of the Israeli occupation authorities did little to deter his resistance. From within Zionist prisons, Daqqa obtained a bachelor’s degree in Democratic Studies in 2010, and later a master’s degree in Regional Studies in 2016. And he continued to write and publish texts that inspired generations of Palestinians. Daqqa enriched the field of prison studies (in which he is now regarded a reference) with novels, articles, letters, and drawings that described the daily realities of Palestinian prisoners in Zionist prisons. His 2010 work, “Consciousness Molded or the Re-Identification of Torture,” shows how Zionist prisons target Palestinian consciousness — the revolutionary spirit, and mind — using psychological torture and isolation to further fragment Palestinian resistance.

Walid Daqqa was also known for the conception of his beloved daughter Milad. In 1996, journalist Sana’ Salama visited Daqqa in prison for an interview. They fell in love instantly and were married behind bars in 1999, with dreams of having a child together. The pair dreamed about Milad for 20 years before she was born in 2020, after they successfully smuggled Daqqa’s sperm out of the Israeli prison he was held in — an ingenious embodiment of the heart of Palestinian resistance: life.

Ten days after his killing, Israel continues to hold Daqqa’s body. The settler colony has long withheld Palestinian martyrs’ bodies to later use them as a bargaining chip. This form of collective punishment amounts to psychological torture for Palestinian families, who have to jump through bureaucratic hoops or wait and wonder for decades before their loved ones’ bodies are returned to them.

This Palestinian Prisoners’ Day, we commemorate martyr Walid Daqqa’s life, resistance, and revolutionary spirit with a translation of his famous 2005 letter, “Parallel Time,” by Julia Choucair Vizoso. She hopes Walid Daqqa’s words move you to refuse and resist the Israel-US genocide of the Palestinian people and destruction of Lebanon, wherever and however you can.

A letter from Walid Daqqa on the anniversary of his twentieth year in prison.

March 25, 2005

My dear brother, Abu Omar, greetings.

Today, the 25th of March, is the first day of my twentieth year in captivity. Today is also the birthday of one of the young comrades, who is turning twenty. This “occasion” has me wondering: How old is Lina these days, now that she is mother to two children? How old is Najla’ who is now a mother of three, or Haneen, who has a daughter… How about ‘Ubaida, who left to study in America, bidding his adolescence farewell without me saying goodbye… How old are my nephews and nieces, some of whom I left as children the day I was arrested, others who were born years after my arrest… How old are my “baby” brothers who are now married with children of their own?

I haven’t asked these questions until now. Time, as a general concept, and how much of it has passed, had not preoccupied me. I have cared much more about how quickly the minutes pass during the brief family visits, which are never long enough for the list of notes and tasks scribbled on the palm of my hand, the ones that require great efforts from Sana’ to even remember them, without the pen and paper that is forbidden during visits. Memory is our only means of remembering. And I forget to contemplate the lines that began etching my mother’s face years ago, and I forget to contemplate her hair, which she began to dye with henna to hide the gray so that I don’t ask her about her real age.

Her real age...? I do not know my mother’s real age. My mother has two ages: her chronological age, which is unknown to me, and her detention age. You can say her age in parallel time is nineteen years.

We exist in Parallel Time, where we see you but you don't see us, where we hear you but you don't hear us.

I write to you from Parallel Time. Here, where space is constant, we only use your normal time measurement units (like minutes and hours) when our temporal lines collide in the visitation room. Only then must we use your units of time, which in any case, are the only thing that remain unchanged in your time, and which we still remember how to use.

I have heard from the incoming youth of the Intifada, and also been personally informed, of many changes in your time. I hear phones no longer have a dial and operate with a card, and that car tires are now tubeless.

I like this new tire system, how the material itself closes its internal gaps automatically, self-containing to prevent leaks. It is like the prisoner who often has no choice but to resist the jailer’s “nails” through self-repair. We have learned that “our driver,” “our drivers," leave no nail on the road without treading on it, no speed bump without making us hit it, thinking they are taking a shortcut. It is not just that our drivers are reckless, but rather that they take this type of “tire” for granted, as if it were not made of flesh and blood, as if it had no purpose. We have been reduced to cash and traded in the market of politics. Take some tires and give us some of the vehicle. What use are the “tires“ without the “vehicle”?

I write to you from Parallel Time. Here, where space is constant, we only use your normal time measurement units (like minutes and hours) when our temporal lines collide in the visitation room.

I hope that the Palestinian and Arab leadership improves. I hope for our people and their political forces to adopt the self-repairing mode of reform, without needing fake mechanics like the Americans and others who are wreaking havoc on Lebanon today.

Yet if we must talk about politics (even though I specifically did not want to today): We exist in Parallel Time, where we see you but you don't see us, where we hear you but you don't hear us. It is as if a glass partition stood between us, its panels tinted only on your side, like the car windows of VIPs. Some of us have come to exude the arrogance of real VIPs. They have managed to convince us we are VIPs.

And why shouldn't that be the case?! The prestige of our situation certainly calls for it. All over the world, there are states and governments that have prisoners. Except us. We are prisoners who have a ministry in a government without a state!

In our parallel time, most of us have no answers to the question commonly posed to children: What do you want to be when you grow up? At 44, I still don't know what I want to be when I grow up!

For those not in the know, we who are in parallel time are in the time before the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union and its socialist camp. We are in the time before the fall of the Berlin Wall, before the first, second and third Gulf War, before Madrid and Oslo, before the outbreak of the first and second Intifada. In parallel time, we are as old as this revolution — before its many factions came to be, before Arab satellite television channels, before hamburger culture took over our capitals, before cell phones, modern communications systems, and the internet. We are part of a history, and history is obviously a state of past events that have ended. Except for us. For us, history is a continuous past that never ends. We communicate with you from this past-present lest it become your future.

Our time is different from yours; time here does not move along the axis of past, present, and future. Our time, which flows while space rests, dropped the concepts of conventional time and space from our language, or it confused them if you wish. Here, we don’t ask when or where to meet, for example, for we always meet in the same place. Here, we travel at ease, back and forth along the axis of the past and present. Beyond the present, every moment is an unknown future we can no longer deal with. Our future is outside our control, like the future of all Arab peoples — with one crucial difference: Our occupiers are foreign and their jailers are Arab. We are in captivity because we search for the future, while their future has been buried alive.

In our parallel time, most of us have no answers to the question commonly posed to children: What do you want to be when you grow up? At 44, I still don't know what I want to be when I grow up!

In parallel time, we are as old as this revolution — before its many factions came to be, before Arab satellite television channels, before hamburger culture took over our capitals, before cell phones, modern communications systems, and the internet.

If Time is the moving dimension of matter, and space is its constant, then we in Parallel Time represent units of time. We are the time that is in a struggle with space, in internal contradiction with it. We have become the units of our time, the points on its axis: the point when so-and-so was arrested, the point when they were imprisoned, the point of their release. These are the temporal coordinates that matter in our parallel-time lives. We know how to set the hour, day, and date by your standards, but we do not. Instead, we use “the day he entered prison” or “the day before (or after) he was liberated.” And because we do not know when another will be arrested, or transferred, we have no way of marking the future on our time axis. So we borrow your time units to speak of the future. Yours is the real time. Yours is the time of the future.

In the dialectic of our relationship with space, we come to form strange relationships with objects in parallel time, decipherable only to those captive in it. How can we explain the bond between a prisoner and the undershirt he was wearing when he was arrested? How can we explain the intensity of our attachment to specific objects whose loss brings heartache and even tears? Objects like a particular lighter or a pack of cigarettes make us so emotional because they were the last of our possessions in the “future.” They are affirmations that we once were outside this parallel time, proof of our belonging in your future. Far from consumer objects to be discarded after use, they transcend materiality. They represent the clutching at straws by those drowning in the depths of parallel time.

In 1996, I heard the horn of a Subaru for the first time in ten years and wept. The car horn in our time serves not to alert pedestrians but to arouse the deepest of human emotion.

In the dialectic of our relationship with space, we come to form strange relationships with objects in parallel time, decipherable only to those captive in it. How can we explain the bond between a prisoner and the undershirt he was wearing when he was arrested?

Like with objects, we form a strange relationship with space in parallel time. Here, one can bond with water stains on the ceiling of their cell, with a crevice in a wall or a crack in the door.

How else can we make sense of the following dialogue, whose fervor, pace, and passion is more befitting an exchange about the gates of heaven than about cracks in a prison cell.

Prisoner 1: Block number 4 is gone… Ah, if only we could go back to the good old days of Block 4.

Prisoner 2: I hear you, but the best thing about Block number 4 was Cell number 7

Prisoner 1: (Sighs deeply, remembering, and interrupting) I already know what you're about to say… That cell allowed you to hear things, the early morning specifically, the sound of cars on the highway

Prisoner 2: (Also interrupting) But much more than that. Remember the door of the cell? That door!! Between the door and the wall, along the hinges, there was a crack, about 2 cm wide… And from your bed you could see the whoooooole hallway, all the way to the end.

Prisoner 1: Man, what use are words… Block 4 really was the best.

How simple the dreams, how grand the human being, how small the place, how big the idea.

I confess that I am still a person holding on to love as if it were embers. I will remain steadfast in this love. I will continue to love you, for love is my humble and only victory over my jailer.

I was not planning to write about time and space today, or about parallel time or anything to do with politics or philosophy. I meant to write about my concerns, about the things I love and hate. Yet my unscripted writing resembles my unscripted life. I confess that nothing was planned. There was no plan to become an activist, a militant, or to engage in any politics at all. Not because I thought there was anything wrong with these paths. To me, politics was not a reprehensible business like it is to some, but it did seem complex and immense. I am not a premeditated activist or politician. I could just as easily have remained a house painter or a gas station attendant, as I was until my arrest. Like many, I could have been married young to one of my relatives, and she could have bore me seven or ten children. I could have bought a freight truck and learned the car trade and how to exchange hard currency. All this might have been possible, until I witnessed the atrocities of the Lebanon War and its massacres. Sabra and Shatila shocked me deeply.

To stop feeling shocked and bewildered, to stop feeling people’s sorrows (any people), to be numb in the face of atrocity (any atrocity) — these became my daily nemesis, how I measured my sumud and steadfastness. A person's mental essence is their will, their physical essence is their labor, and their spiritual essence is their ability to feel. Being able to feel for people, feeling the pain of humanity, is the essence of civilization.

It is this very essence that is targeted in the life of a prisoner, hour after hour, day after day, year after year. You are not targeted as a political being in the first instance, nor as a religious being, nor a consumer from whom the pleasures of material life are denied. You may adopt any political conviction, practice religious rituals, and have many consumer needs met. The primary target is the social being, the human within you.

The target is any relationship you can have outside of yourself, with other people, with nature — even with the prison guard as another human. They do everything to make us hate them. The target is love.

I was not planning to write about time and space today, or about parallel time or anything to do with politics or philosophy. I meant to write about my concerns, about the things I love and hate. Yet my unscripted writing resembles my unscripted life.

In my twentieth year of captivity, I confess that I am still not good at hatred nor the harshness that prison life can impose. I confess that I still feel childlike joy for the simplest of things. A kind word, a compliment, any encouragement will fill me with joy. I confess that my heart flutters at the sight of a rose on television, or a nature scene, the sea. I admit that despite everything, I am happy. I do not miss any of life's pleasures, with two exceptions: the scene of children coming together across the village on their way to school in the morning; the scene of workers pooling from alleys and neighborhoods into the town center, commuting to their workplace on a cold, foggy winter morning. And I admit that none of these emotions, none of this love, would persist without the love of my mother Farida, of Sana’, my wife, of my brother Hosni, or without the succor of family, friends, and loved ones.

I confess that I am still a person holding on to love as if it were embers. I will remain steadfast in this love. I will continue to love you, for love is my humble and only victory over my jailer.

My regards... Milad