Searching for Lebanon’s Ancient Ruins Amid Capitalist Ruination

A few days after the Beirut port explosion, I approached the Saifi Plaza construction site with a sinking feeling. Six years earlier, I had witnessed a rare discovery there. Deep in the bowels of its multistorey excavation hole, under a canopy of white tents, I watched archaeologists toiling over a patchwork of large interlocking sandstone blocks believed to be part of an ancient wall once encircling Berytus, one of the most storied capitals of the Roman empire.

I had not seen the inside of the Saifi construction site since 2014, and had no idea what became of the ruins. The state antiquities authority rarely communicates with the general public about ongoing digs or much else concerning Lebanon’s rich cultural heritage. Little has been published about its dozens of discoveries over the last two decades. Even in 2014, documenting the site was not easy. The minute I tried to take a picture, the lead archeologist sternly forbade me, even threatening legal action although I was standing on a public street overlooking the open air dig. I’m so glad I didn’t listen and documented the ruins anyway — as I have done for dozens of sites across Beirut despite similar threats from real estate developers and state bureaucrats. I have always felt a wider audience deserved to know about the illustrious history being uncovered in their city and how they were being excluded from decisions over what stays and what goes.

For the better part of the last decade, Saifi Plaza and many other construction sites in downtown Beirut have been hidden behind plywood, concrete, and metal panels that served multiple purposes. Ostensibly acting as safety barricades, they have increasingly become advertising billboards, displaying artist impressions of sleek towers with hanging gardens promising “urban luxury.” But perhaps their most important function has been to conceal national and world heritage treasures from the public for commercial and residential projects that less than one percent of the population could afford to enjoy. To steal a peak at this history and document it, I had to use my phone camera as a periscope to peer through small gaps in these walls. And from the little I could make out during that time, there was some cause for hope for the ruins at Saifi Plaza. Only two of the project’s three office blocks (designed by local starchitech Nabil Gholam) had been completed, while the remaining plot, where much of the ruins had been found, appeared unbuilt.

A man walks past the Saifi Plaza construction site, its walls re-erected after they were destroyed by the port explosion on August 4, 2020. Beirut, Lebanon. February 17, 2021. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

It took the explosion of August 4, 2020 to find out what really happened. The blast wave that shattered thousands of homes within the four kilometer radius of destruction also collapsed the walls surrounding many of these massive and secretive real estate projects in downtown Beirut. The walls of Saifi Plaza, once adorned with marketing slogans like “steps away from shopping and history,” were now mangled and blown open, hanging by a thread, like much of Beirut.

An eerie calm hung over downtown, the historic city center, which is located just a few blocks from the city’s harbor, the epicenter of the explosion. It was one of those rare moments where you could walk its streets without fear of being watched or chased or assaulted, as I and so many others had been before. This fleeting feeling of freedom was reminiscent of the early days of the 2005 and 2019 protests; a feeling of owning the streets, abandoned briefly by their guards.

The blast wave that shattered thousands of homes within the four kilometer radius of destruction also collapsed the walls surrounding many of these massive and secretive real estate projects in downtown Beirut.

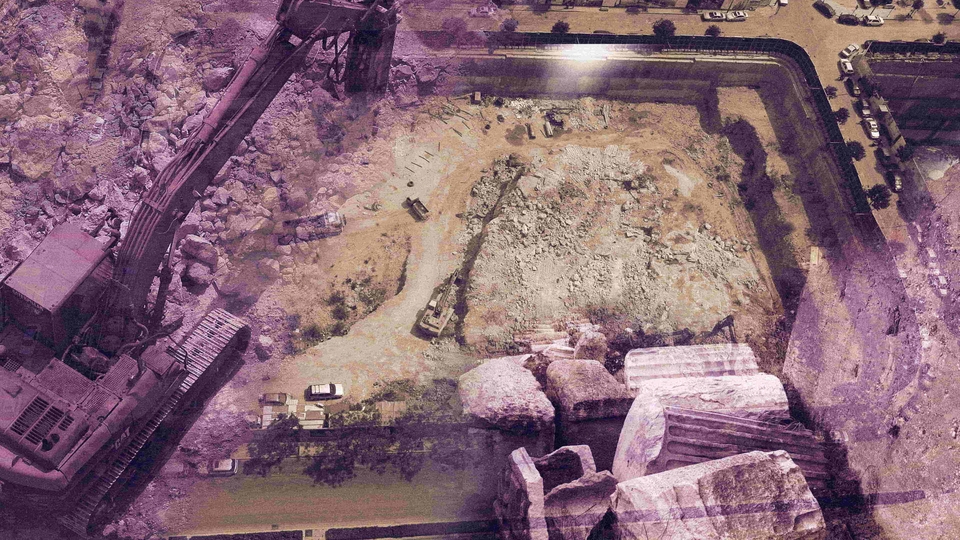

But when I excitedly peered over the edge of the now completely exposed site, I could see nothing but a deep dark pit, a cesspool-like swamp in the place of the remnants of the city wall and other structures. There were no signs of even a concrete foundation. It was as if the investor had just run out of money and priceless history had been destroyed for no reason. Sadly, this was not an isolated case. The city is full of empty ditches where ruins have disappeared to make way for speculative real estate that never materialized.

A cesspool-like swamp is all that remains of the ruins of the ancient wall once encircling Berytus. Saifi Plaza, Beirut, Lebanon. August 2020. (Habib Battah/The Public Source)

I walked from Saifi Plaza to the site of another multi-million dollar project that had unearthed another piece of the puzzle of ancient Berytus, a bank tower designed by Pritzker-prize winner Renzo Piano. Both sites are located on George Haddad Street — a treasure trove of ruins which begins near the water’s edge and runs up the foot of Ashrafieh hill, where Bronze age, Roman and Byzantine sites abound. I was physically assaulted in 2013 for documenting some of these plots, which have now become posh cafes and high end condos, leaving the Saifi Plaza and Piano tower construction sites as the last remaining windows into this illustrious underground past.

Hidden behind a barricade, this site was meant to house a bank tower designed by Italian celebrity architect Renzo Piano. Beirut, Lebanon. February 17, 2021. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

During the excavation for the Piano tower, an entire well-preserved Roman-era neighborhood was discovered. The site, which spanned the entirety of the project’s city block-sized footprint, contained dozens of interconnected rooms and stone structures, similar to what one might find in the middle of a Greek or Italian city. I documented it in 2018, sneaking a shot from nearby rooftops or during brief openings in the site door to let construction vehicles in. Clearly determined to keep prying eyes out, the perimeter had been heavily surveilled through a series of cameras mounted on its walls and around the clock watchmen. A few years ago, one threatened to send men to my home to teach me a lesson, just because I had taken a photo from the sidewalk. No official information was made public about the fate of the site.

Like Saifi Plaza, now that its walls had collapsed and watchmen abandoned, it was clear that nothing remained of the sprawling chunk of the ancient city but a gaping pit in the ground, tens of meters deep.

A gaping pit in the ground, tens of meters deep, left by the removal of the ruins of a well-preserved Roman-era neighborhood to make way for a bank tower that never was. Beirut, Lebanon. August 2020. (Habib Battah/The Public Source)

Of course it would be naive to be surprised. All of this follows a well-rehearsed, historic pattern. Downtown Beirut has always been a graveyard of dreams and political ambitions. Buried deep in its rich layers of rock, dirt and garbage is an archaeology spanning millennia of human development. Much of it was unearthed during the last three decades only to be destroyed, lost or buried again.

The city is full of empty ditches where ruins have disappeared to make way for speculative real estate that never materialized.

Perched on a hill above the city’s harbor, the old city, formerly known as Al Burj was rebranded Beirut Central District (BCD) or “Downtown” in the early 1990s. It was part of a multibillion dollar, privately-funded project to reconstruct Beirut led by the country’s then billionaire prime minister Rafik Hariri. “Beirut, the ancient city of the future,” was one of its early marketing slogans.

However, out of at least 120 archaeological discoveries recorded in the 1990s and dozens more excavations since, less than 10 have been made accessible to the public in situ, the vast majority having vanished, either into decaying warehouses, poorly documented and thus irreparably damaged and devalued, or bulldozed entirely. A towering fifth century BC carved rock site that many believe to be one of the world’s earliest ports, was chiseled to a pulp by jackhammers in 2013 to build the Venus Towers, a series of towers designed by another Pritzker-prize winner, Spanish architect Rafael Moneo. Almost a decade later, this project too remains unfinished, having been sold to a new investor amid rumors of financial problems.

A decade-old panoramic view of the site that once housed the ruins of a Phoenician port, later removed to make way for one of many abandoned real estate projects. To the right, the ruins of ancient Beirut’s hippodrome, since replaced by luxury villas. Beirut, Lebanon. June 26, 2012. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Many archaeologists have protested the lack of transparency of Lebanese antiquities authorities. In a scathing rebuke of the secrecy of the organization and its rushed approach to excavations, Helene Sader, the chair of archaeology at the American University of Beirut, alleges that countless sites have been destroyed across the country. At least a dozen archaeologists have approached me privately over the years, desperate to save sites but fearing they will lose their jobs if they speak out publicly. The head of the state’s Directorate General of Antiquities could not even tell me how many excavations have been taking place in Beirut, during a recent interview.

The justification for razing much of the old city to build the BCD project was that it would bring massive economic benefits for the entire country, putting it on the map of international investment. And by the mid 1990s, the BCD had indeed become one of the largest construction sites in the world. To witness so many cranes and hardhat workers banging away in a bombed out city, ripped apart by decades of bullet and projectile holes, there was a feeling of possibility and rebirth everywhere you looked, fueled largely by Prime Minister Hariri’s unflinching confidence — or at least the appearance of it. On Hariri-owned (and aptly titled) Future TV, the biggest channel back then, a time lapse sequence was often played during commercial breaks: workers on scaffolding plastering ruined buildings and gradually patching up all the bullet holes until the facades were shiny and new again.

Every new building in the country was an attraction to visit, a sight for sore eyes, tired eyes accustomed to a dense, dilapidated and endlessly bruised and scarred landscape. Lebanon had a meme before the age of the internet. “It’s like Beirut in here” was a cliche line heard in countless Hollywood films and news reports. Thus, each and every international company or restaurant chain to set up in Beirut felt like another goal post in reaching acceptance by the rest of the world. Richard Branson famously arrived on a bulldozer to inaugurate the Virgin Megastore in the former battlefield that was Martyrs’ Square. By the late 1990s, Julio Iglesias and Luciano Pavarotti had performed; McDonald’s and Burger King opened to lines wrapped around the block, two Hard Rock Cafes competed for authenticity (one a well-crafted fake complete with a massive guitar-shaped sign); even American diner chain Johnny Rockets had set up a drive-in movie theater in a parking lot on the edge of the BCD’s massive construction site.

There was a desperate feeling in the country to overcome the violent reputation of the past, to rejoin the world, repair and rebuild. I myself, and so many around me, were caught up in the feeling of a renaissance. But the damages were not as easy to fix as we were led to believe. Our destruction was not just a scar to be bandaged, a bullet-riddled facade to be patched up and repainted.

By the war’s end, all of Lebanon had holes in it. It was hard to find a wall without one, or a window that was not cracked. But as a fault line in so many of the city’s conflicts, Al Burj was particularly grim and creepy. Most of its urban fabric, rows of abandoned French-style 1920s buildings, were reduced to crumbling, swiss cheese-like facades, ravaged by an incalculable number of bullets, shells, and shrapnel. The ambitious plan to make it all new again called for a tabula rasa approach: to raze most of the old and rebuild a modern grid from scratch, led by the world’s most famous architects and urban planners. Sketches of their imaginative new structures and vast green spaces were splashed across billboards and television commercials. There was even a large-scale model of the future Beirut, showcased at the offices of Solidere, the private firm undertaking the work. It featured a machine that simulated tidal waves slapping up against the newly built, billion dollar seawalls intended to protect the city from tsunamis. It all looked great, they had thought of everything. And as journalists, we ate it up.

At the time, I was an eager young reporter at the now defunct Daily Star newspaper and my colleagues and I at the businesses desk relished each new issue of the Solidere annual report we received. They were loaded with high gloss images of the latest plans and futuristic towers, even centerfolds for us to ogle over. Technocrats of the finest caliber working on our little blown-up city, a dream come true, a breath of fresh air from the shell-shocked, garbage-strewn streets we were used to. But amid all the fanfare and media hype, one question was rarely asked. For whom? Who would this new city serve? Who would live and work here?

Sure we printed criticisms, but these were mainly related to the execution, not the product itself. The conflict of interest in a prime minister being the biggest shareholder of the biggest reconstruction company was as plain as day and we often played it up. I was once berated by my editors for publishing a story questioning the ownership structure of Solidere after its legal team had paid them a visit and threatened to sue us, forcing a retraction. Of course this drove my interest even further and I began to pursue the legal angle, the way in which properties were seized by the state. I interviewed Solidere’s chief critic at the time, the owner of the famed St. Georges seafront hotel, who had refused to sell his property to the company, and claimed that he had been barred from obtaining renovation permits as a result. But this time my editor prevented any publication and I was told the hotel owner’s name would never appear on our pages again.

What I would later realize is that it didn’t matter who owned the project or how it was structured, fundamentally it was not designed to serve the local population. There were some scattered acts of resistance and attempted lawsuits, but these were easily quashed in the time before the internet.

Out of at least 120 archaeological discoveries recorded in the 1990s and dozens more excavations since, less than 10 have been made accessible to the public in situ, the vast majority having vanished.

Throughout much of the 30 years since the BCD took off, the shiny new city that emerged has largely remained as abandoned as it was during the war years. Despite a brief honeymoon period in the early 2000s, when tourists from oil-rich surrounding states flooded its high-end restaurants and luxury retail outlets, the BCD’s prices and offerings remained far out of reach of the local population, who were alienated by the vast changes to the city center of their childhood memories. Entire streets and neighborhoods had been erased, often turned into parking lots. The astronomical price of housing, with the smallest apartments selling for millions of dollars, also helped ensure the emptiness of the space. Once the tourists had gone home, who would stroll through its shops and cafes if no one could afford to live there year round?

The only draw for the general public, the promise of heritage preservation, museums, and public parks has yet to materialize. These include Shoreline Walk, The Garden of Forgiveness, a central park, and the Martyrs’ Square redesign — lush and sprawling open air public spaces designed by award-winning international architects. And yet all remain sketches, surviving only on the servers of Solidere’s website and in its promotional materials. Instead, the handful of open spaces that were actually constructed since the 1990s never seemed to be intended for public consumption: small, sterile, hardscaped plazas that could easily be missed, tucked in between towers. They offer little shade, few chairs, no public facilities such as bathrooms, picnic or play areas. The most prominent of these is Zaitunay Bay, famously policed by private security agents, eyeing loiterers with suspicion and banning all sorts of activities, including bikes, skates, music and food. Indeed these spaces felt more like artistic flourishes to compliment the elite high rises that surrounded them, eye candy for those looking down rather than an attraction for those passing through below.

The irony is that Beirut’s organic archaeological discoveries could have provided so much more cultural richness and local value than the prefabricated and imported materials and concepts that were employed. In its advertising and publications, the BCD modeled itself on upscale areas in Western capitals: London, Monaco, Paris. Even today the company’s website is only available in English. The local context was divorced from the project at the outset, a virtual cordon sanitaire — a highway overpass — separates the BCD from poor neighborhoods that used to flow seamlessly into El Burj.

Beirut’s famed outdoor markets, or souks, which brought people together from different income levels and regions, were replaced by a designer shopping mall, also created by Rafael Moneo. Only the finest materials were used to craft the project, lined with carved granite chevron facades. Its curved aluminum-paneled cinema building beams a light display across the length of its parallelogram shape, and features LCD screens as its ceiling panels. At the same time, most people in Beirut and Lebanon face severe electricity and potable water shortages, both now and at the time of construction.

Redeeming himself somewhat after the pulverizing of the Phoenician port site, Moneo’s “Beirut Souks” attempts to integrate ruins discovered during construction, among them a Persian-Phoenician neighborhood and a crusader-era city wall. But these sites serve a largely decorative purpose, locked underground behind steel gates or tucked in a ditch in between shopping corridors. The public is only invited to look from a distance, not to interact meaningfully with the site.

The “reintegration” approach modeled by the Beirut Souks means ruins found on a site are returned after construction and incorporated into a private property, typically a garden or underground basement. It has become a PR coup for Lebanese antiquities authorities seeking to create a narrative of balancing preservation with the needs of multimillionaire developers. This was the case with the discovery of ancient Beirut’s chariot race track or hippodrome, unearthed in the late 2000s only to be completely gutted and transformed into luxury villas financed by bank owner and former minister, Marwan Kheireddine. As a compromise, Kheireddine offered to display a short portion of the hippodrome wall, deep in his real estate development’s basement car park. The design calls for a window at street level that would allow only a glimpse at what would appear to most as an unintelligible pile of rocks. But even that minor level of access is not guaranteed, as the streets leading to the site are often closed to both traffic and pedestrians due to the luxury condos’ proximity to the prime minister’s home.

It remains unclear if Renzo Piano’s bank tower will also make use of integration, if any of the ruins that were cleared from the site were salvaged. But again how much access will the public have to a private office building in the most expensive part of town? Would Piano even be allowed to embark on such a wide-scale erasure of a Roman city in his home country of Italy?

It seems Piano had already planned his rebuttal. Among his other lucrative downtown Beirut projects is the long-awaited Beirut History Museum. Announced in 2018, the striking all-glass structure would finally provide a transparent interface to display the postwar archaeological discoveries that have been hidden from public view, including a live excavation on its lower level. As noted on its construction walls, “ the museum inhabits the archaeological excavation.” Indeed, initial digging for the project did uncover a number of ancient structures, well preserved interconnected buildings with what looked to be a road cutting through them. But why would one build a museum on a site that is already an open air museum? Why destroy a site for the stated purpose of displaying it? Rather than “inhabit” the past, the museum project has literally eviscerated it. Once again, the discoveries have today been replaced by a giant gaping hole in the ground.

The intended spot for the Beirut History Museum, a site that is already an open air museum. Beirut, Lebanon. February 17, 2021. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Contrast Lebanon’s reintegration strategy to the treatment of comparable discoveries in Europe. Like the Berytus racetrack, Rome’s Circus Maximus is largely a barren field and does not contain an abundance of structures — the justification Kheireddine and the antiquities department used to argue for its destruction. Yet in Rome, the circus remains are a protected public space, where thousands of locals converge for concerts and festivals. In Athens, a large and mysterious ancient carved rock site is part of a public park overlooking the Acropolis. Locals often sit on its edges to enjoy a sunset. Can we imagine the view of the Mediterranean from the rock wall site eviscerated for Moneo’s Venus Towers?

Throughout Europe, Roman walls have been a major attraction, often reconstructed at great lengths, creating walking paths and tower viewing points linking the city and anchoring it to an illustrious past. But nothing of the sort had ever been considered for the numerous fragments of the Berytus city walls and towers discovered and disappeared in private real estate construction sites across the city over the last few decades. In 2018, a well preserved section of the wall, along a rare Roman royal cemetery was uncovered only to be dismantled, despite protests at the time.

Throughout my career, I have heard the arguments in defense of prioritizing private capital over archaeology so many times, told to me by politicians, real estate developers and even state heritage officials. Do you want to turn the whole city into a museum, they quip. What about the economy, what about all the money these projects will bring to the country? We can’t stop progress, they say. But what these rousing and yet simplistic arguments often lack is specificity in their calculations or any sort of realistic cost-benefit analysis.

Of course massive construction projects with big name architects require armies of workers, but most of these jobs are temporary and low paid. The workers usually come from Syria or South Asian countries and are thus poorly treated: they often face injury or even death with no basic safety or health care on the overwhelming majority of construction projects. And then most of their modest earnings are sent back home.

On the other hand, the high end construction materials, marble, and cement come at a high cost to the environment. Illegal and unregulated rock quarries established in every valley of the country have defaced Lebanon’s once pristine natural environment, causing untold health problems to nearby villages and the ecosystems that sustain their livelihoods. The transportation of these heavy materials, mainly via ancient dump trucks, spewing plumes of unfiltered black diesel exhaust, further erodes the city’s already crumbling road networks, and causes massive traffic jams on century-old city roads designed for horse carriages. Once completed, the towers have a similar impact, causing a heavy strain on overburdened water, sewage, and electrical networks that are barely functioning to begin with.

The irony is that Beirut’s organic archaeological discoveries could have provided so much more cultural richness and local value than the prefabricated and imported materials and concepts that were employed.

These are costs that must be absorbed by the state and its citizens, while developers pay little to no taxes on their properties and profits. Indeed it is this lack of basic regulation on material production, safety and environmental impact, workers’ compensation and negligible taxes that make real estate such a lucrative, low overhead and high return industry in Lebanon.

A wide range of less tangible costs also escape the calculation of unfettered capital enrichment. As we have seen from examples in Europe, archeological parks can be used for exercise, recreation, or even as small-scale community gardens. They can reduce stress, improve creativity, and help build community relationships. Studies show people are healthier and more productive when there are opportunities for recreation and public space. Today Beirut is one of the world’s least green cities. While the World Health Organization recommends 9 meters of green space per capita, Beirut provides just 0.8 meters.

Lebanon’s ruins also provide windows into possibilities and meanings that may help us look beyond the defeatism, hopelessness, and even self-loathing of the current political discourse. It is all too easy to dismiss Lebanon as the center of backwardness and corruption, the trademark patronizing claims of post-colonial orientalism that have become so deeply internalized by locals. Archaeologies and places to think about them can offer alternative, more generous and humanizing narratives.

Lebanon was home to leading institutions of political and religious learning and coexistence, both in the modern and medieval periods, including noteworthy political philosophers, dissidents and scholars of Islam, Judaism and Christianity. An appreciation of the many faiths and tribes and ideologies that passed through could soften the cultural, religious, and political divisions that persist today. Too often, Lebanese archaeology is focused on the Roman and Phoenician periods, politicized as self-affirming narratives to those who claim a Western or Christian identity as supreme. But Lebanon’s Sunni, Shia Druze and Jewish heritage needs to be better excavated and given similar value as a contributor to the nation and the world.

Over a thousand years earlier, Berytus was recorded as a “splendid metropolis,” critical to the development of the Roman empire; its law school was one of the world’s first, a far cry from the daily chaos of today. Lebanese now beg for international help to investigate crimes and develop their justice system, yet the foundations of basic law practiced around the world today were pioneered in Beirut.

Going even further back, during the Bronze Age, the archaeological record tells us Lebanon played a significant role in early world trade and industry, from language development to creating global supply chains. The world’s oldest weighing scale was recently found in North Lebanon; oil, wine and Cedarwood produced here was shipped across the Mediterranean, used to construct many wonders of antiquity, including the temples and furniture used by the Pharaohs in Egypt. We can even look to the very beginning of human civilization, when Stone Age settlements in the city and its environs testify to mankind’s earliest stages of development, cohabitation with Neanderthals and passage to Europe when the lands that are currently Lebanon formed a central part of what is known as the paleolithic corridor out of Africa. Sadly most of the country’s prehistoric sites have been flattened, often converted to modern cement quarries.

Can we imagine the view of the Mediterranean from the rock wall site eviscerated for Moneo’s Venus Towers?

These are not just lessons for historians or foreign tourists, although tourism can provide great benefits to small businesses barely holding on in the shadows of the emerging towers. The primary beneficiaries of local spaces can also be local people: students on school field trips that bring textbooks to life, or office workers and passersby looking for a place to have lunch, to think or imagine or just rest. There is great value in custodianship of world wonders, not to claim them as our own, but to preserve and share with others. But there are major hurdles to get there.

For one, preservation costs money, lots of it. Public space projects are typically funded by state income tax revenues, which are largely non-existent in Lebanon, despite the fact that the country has very little natural resources or industry. The entire BCD project was sold as tax free, and thus the municipality of Beirut lost billions of dollars in taxable income as a result. This is a testament to a laissez-faire economic order, entrenched in the colonial period and encouraged in much of the global south, to entice foreign investment. But this strategy comes at the cost of local development, bleeding antiquated public institutions of desperately needed resources.

The lack of state revenue negatively impacts all state institutions, already gutted by the wars. The budget of the Directorate General of Antiquities appears not even able to cover basic maintenance of sites. In fact, mosaics located right across the street from its offices are overgrown with weeds and littered with garbage, eroding with no protection from the elements. Only five professional archaeologists are employed by the DGA to cover the entire country, according to a senior archaeologist. I could not even get a figure for the DGA’s budget during an interview with its head. Meanwhile, entrance fees to UNESCO world heritage treasures such as Baalbek, home to the best preserved Roman temples in the world, are only a few dollars, a pittance compared to their counterparts in Europe or the Middle East. At the same time, the country, racked by new wars every decade, cannot attract the tourism numbers that would help sustain the economy.

Today, as we peer once more into the abyss of Beirut’s latest destruction, the miles of flattened spaces around the port site, many architects and investors around the world see yet another canvas to exercise their imaginations, and profit margins. Once again, artist impressions are promising modernity and greenery and public access, projects worth billions of dollars. But those genuinely interested in revival and redevelopment, should be wary of the lessons of the past. A city or a country cannot be reconstructed without earning the confidence of the people who live there and making them an immediate priority. It is their input and inclusion that will either breathe life into the rebuilding effort, sustaining its businesses and occupying its homes or abandoning it altogether, left to decay like so many white elephant projects in Lebanon and across the world.

As a journalist, I cannot count how many press conferences I have attended aimed at wowing audiences with glossy imagery, luxurious amenities and ambitious claims to be on a par with international capitals. Looking back, few of those plans ever succeed. What these failures shared in common was an intense focus on facades, bespoke building materials, luxury amenities, buzzwords. They were benchmarked to an imagined modernity existing in some other part of the world, failing to ask about the mundane challenges of everyday life and everyday people at home, living all around them. Above all, development cannot be a slideshow presented to the public, it must be a collaborative and inclusive project, designed and implemented by those it is intended to serve, and those who will pay for it.