Digging Through the Archives for the 1987 Strike That Braved the Barricades

Because of an unprecedented economic crisis affecting the lower and middle classes, a growing number of Lebanese families simply are no longer able to afford food, medicine or education… A combination of political malaise, lack of confidence in the [Lebanese] pound and speculation has all but stripped the currency of its once-envied purchasing power... Some families are eliminating meat, eggs, cheese and fruit from their daily diets… Garbage scavengers are beginning to appear... One pharmacy that used to be open 24 hours a day put up a notice saying it was ‘closed because of a shortage in medical supplies and medicines.’

This newspaper excerpt is not from last week, last month, or even last year — it’s from a Los Angeles Times article dated November 1987. Are we stuck in a time loop? It’s as if 34 years never passed, or perhaps they did, but somehow we are back to square one. Did we ever leave it? Feminist scholar Maya Mikdashi expressed this feeling in a resonant aphorism, writing that “the years take shape as a circle, not a line.”

At the time, in 1986, economist Nasser Saidi wrote about the economic consequences of the war, describing how “Lebanon… stands on the brink of widespread poverty, social unrest, rising inflation verging on hyperinflation and a rapid depreciation of the Lebanese Lira on the foreign exchange market.”

History is brimming with antidotes to despair, and that is its power. Radical moments from the past can fan today’s embers of popular dissent, but only if we dust the past off of these moments and bring them into the now.

Now, that “brink” is high up and most have fallen down, sick and hungry in the dark. Meanwhile, hypocritical calls to #giveLebanonachance, helpless hopes in elections, and prickly attachments to federal divisions are like public appeals for faith in supernatural levitation.

Then, amidst war, Israeli occupation and economic depression, workers rallied behind the slogan, “against the rulers, against the government, against the militias.” November 5, 1987, became the first day of their general strike.

Today, sustained organizing is tenuous, even more so after the seeming defeat of October 17, and we may be witnessing the third “exodus” from Lebanon since World War I.

Still and all, capitulating to despair leads to loss after loss.

History is brimming with antidotes to despair, and that is its power. Radical moments from the past can fan today’s embers of popular dissent, but only if we dust the past off of these moments and bring them into the now.

That’s why we are returning to the eve of the 1987 general strike to agitate against makers of war and dispossession, and remember with its witnesses and organizers how workers braved the barricades.

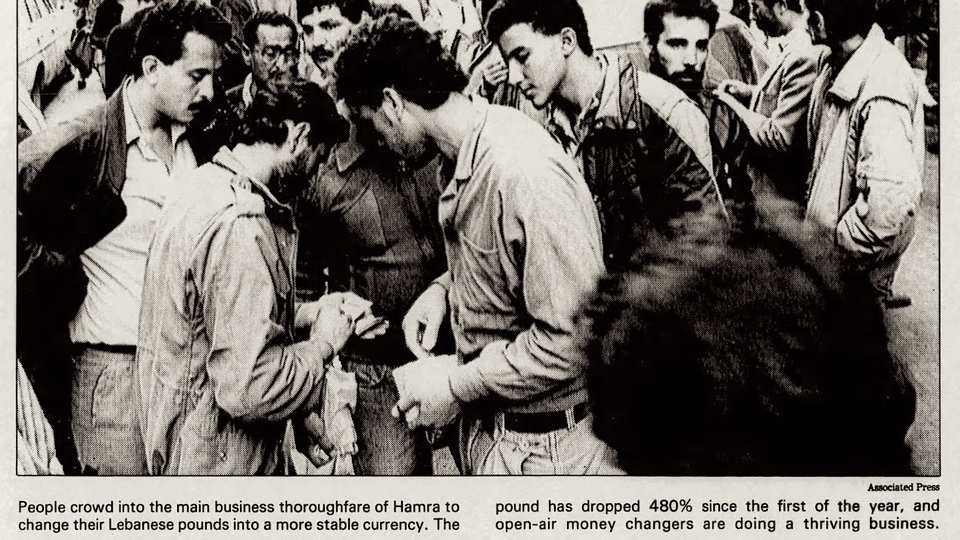

Nora Boustany’s article in the Los Angeles Times from November 29, 1987 has since become a classic.

A Monstrous Mutation

In the decade before the strike, small mobilizations emerged in “civil resistance” to the civil war.

Sociologist Ghassan Slaiby, a former adviser to the General Confederation of Workers in Lebanon (GCWL), recorded 114 such mobilizations between 1975 and 1984. These included summer camps, sports activities, art exhibitions, blood drives, “Christian and Muslim women-led peace marches,” and mock checkpoints distributing sweets and flowers.

Their largely middle-class participants gathered under the banner of “a united Lebanon” to challenge the idea that Lebanese society is allegedly perpetually fragmented. However, these responses to the sectarian discourse of the war could not address the economic realities of the war and of the preceding decades.

Indeed, it would be a grave historical mistake to assume that the civil war represents a radical rupture with the political-economic order of postcolonial or even postwar Lebanon.

“Free market” non-interventionism in the so-called “golden age” of Lebanon in the sixties had left over 50 percent of households across the country in poverty or destitution. Class antagonism boiled to a brief civil war in 1958, then a strike in 1972 at the Gandour factory.

In 1975, militias went to war and initiated a “monstrous mutation” within the political-economic order, in the words of historian Fawaz Traboulsi.

“It has been said that wars have no sense but functions,” writes Traboulsi, and in Lebanon, the civil wars became the political, military, and economic opportunity to co-opt the state and seize the economy.

Militias exerted “a parasitical politico-military levy on practically all economic activities,” he continues, smuggling “cigarettes, drugs, arms, contraband commercial goods” through the ports they controlled during a “war waged against the state and its citizens.”

These mutations maintained, if not deepened, earlier social hierarchies, consolidated the militias’ control over infrastructures and wealth, and paved the way for the neoliberal privatization schemes of the nineties.

This war, then, was not only a war over spoils and dominance. It was also a class war and a war against the social state.

Despite these monstrous mutations, the first seven years of the civil war (1975-1982) have been described as “war in a time of abundance,” a time of “prosperity despite war.”

This war, then, was not only a war over spoils and dominance. It was also a class war and a war against the social state.

This supposed prosperity was linked to the region’s “oil boom,” as many Lebanese emigrated to the Arab Gulf for work and began sending remittances to their families.

In 1980, they sent over $2.2 billion in remittances. Seven years later, however, that number plummeted to $300 million, following an “oil glut” that had begun in 1981 that caused oil prices to crash in 1986.

Meanwhile, local banks were orchestrating an organized speculation on the Lebanese Lira, especially between 1986-1988, which accelerated the war’s economic impacts. In 1984, following the Lira’s alarming loss of value, a different movement began to grow under the leadership of the GCWL.

By November 1987, the dollar traded at 498.21 liras. Living conditions became so deplorable that late sociologist Salim Nasr reflected, in retrospect, how “many Lebanese [could] not comprehend the dramatic change, let alone cope with it in their daily struggle for survival.”

The workers’ strike of 1987 is then part of the long class struggle, this time against the monstrous mutations executed with the tank and barricade.

An Anti-War Workers’ Movement

“There were social, economic and military factors that allowed us to organize the general strike,” Slaiby tells The Public Source in an interview conducted over the phone. “The militias that started the war and were ruling over their territories with an iron grip had weakened [over time], and their incompetence and actions had cost them a lot of popular support.”

That formerly allied militias had turned against one another presented an opportunity for the workers’ movement to act.

“Imagine if the Lebanese Forces and the Kataeb were still unified and controlled 100 percent of their territories, or if the Lebanese National Movement was still unified and in control of West Beirut, people would not have been able to unite and come out to the strike,” he muses.

In a country that had effectively disintegrated, “the GCWL had maintained its unity,” Slaiby continues. “It had gained a lot of legitimacy. People trusted it!”

That formerly allied militias had turned against one another presented an opportunity for the workers’ movement to act.

Adib Bou Habib, General Secretary of the Printing Press Employees’ Trade Union, concurs. In a phone call with The Public Source, he expressed that “the whole union movement was against the war, regardless of [individual] political or ideological viewpoints.”

On June 23, 1986, the GCWL issued a statement naming July “the month of popular struggle to save Lebanon from war and impoverishment.” In practical terms, the month became a day of striking and countrywide protests, one that, nevertheless, set the stage for direct confrontation between the workers and the militia-dominated political order.

Assafir reporting on the First National General Syndical Conference, on May 8, 1987.

On May 7, 1987, according to Assafir, over 120 representatives from the GCWL and smaller organizations, including the private school teachers’ union and the liberal professions’ syndicates rallied under the banner “no to war, yes to national consensus, no to the state’s system of starvation, yes to rightful demands for livelihood” at the Fransiscan School in Beirut where they held the first National General Syndical Conference (al mu’tamar al niqabi al watani al ‘am).

“The National General Syndical Conference was more of a network to coordinate actions and issue joint statements, rather than a formal organization with a structure, a president, a secretary, and so on,” Slaiby explains. “The presence of the GCWL in the Conference gave it a lot of legitimacy and popularity. The GCWL was the Conference’s dynamo.”

Progressive taxation, increased government spending on essential services, urgent measures to curb speculation on the Lebanese Lira, universal healthcare, affordable housing are some of the key demands that remain pressing today.

Assafir published the conference’s concluding statement which included a list of social and economic demands that the assembly had ratified.

Progressive taxation, especially on profits accrued from real estate transactions, increased government spending on essential services, like electricity and public transportation, urgent measures to curb speculation on the Lebanese Lira, universal healthcare, affordable housing, a pension law, expanded and improved public education, state intervention to support productive sectors of the economy and food self-sufficiency are some of the key demands that remain pressing today.

Crucially, the conference tied social and economic redress with the “full and final cessation of the war” and the “struggle toward liberating the nation and supporting the national Lebanese resistance against the [Israeli] occupation by all means,” the first two articles of the concluding statement.

The end of the war must be complemented with “a non-sectarian political solution,” reads the statement, “that ensures national consensus internally to guarantee the unity of land, people and institutions, the sovereignty of the nation, and its complete independence.” This solution would be founded on “political reforms to eradicate the manifestations of sectarianism and its foundations within the state, its institutions, and laws… unifying the Lebanese on the basis of belonging to the nation and not the sect.”

Escalations

Larger than the first, the second National General Syndical Conference was held on September 30, 1987. At the time, Bou Habib was head of the GCWL’s Council of Representatives, and he played an active role in organizing the conference.

He describes to The Public Source how the conference drew “all of the federations of unions, the Lebanese University professors’ union, women’s groups, and private school teachers,” among others.

“Many important groups and syndicates that were not formally part of the GCWL played an active role,” Dr. Hiam Keyrouz tells The Public Source during an in-person interview on December 6, 2021.

Keyrouz began her engagement with the workers movement in the 1980s as a research assistant with the GCWL. Today she directs the Printing Press Employees Trade Union’s public outreach and communications, and works within the GCWL administration, although she is critical of the Confederation’s performance.

According to Keyrouz, lawyers, teachers in private and public schools, and university professors rallied around the GCWL in the second conference, then took part in the general strike.

In a subsequent interview on February 1, 2022, she told The Public Source that many of these figures were leading women’s organizations and played an important role in the conference.

The late Wadad Shakhtoura is a pillar of the feminist movement in Lebanon who founded the Lebanese Democratic Women’s Gathering (1976). Feminists fondly remember her for her lifelong commitments to the Communist Action Organization, the teacher’s union, and the feminist movement as a whole. Keyrouz mentioned that Shakhtoura was involved in the preparatory meetings and strike.

Linda Matar was also part of the conference. This longtime organizer and activist for women and labor rights, close to the Communist Party, had spent a part of her childhood working in a silk factory, before channeling her organizing with the Committee for Women’s Rights toward improving the conditions of women factory workers in the southern suburb of Beirut.

The Public Source tried to contact two feminist figures who were part of the second conference to understand their priorities at the time and the political and organizing directions they were pushing for but personal circumstances were not favorable to get their perspectives.

The assembly in the second conference committed to a countrywide protest on October 15 in preparation for an open-ended general strike on November 5. “Against the rulers, against the government, against the militias” was the slogan.

On the eve of the general strike, Assafir published an editorial, titled “The Strike and Unity,” to underline the historical importance of the general strike. “More than a syndical event,” it is a united front “against the militias’ hegemony.”

Assafir agitated against “the militia system,” describing it as “wholly bankrupt and incapable of achieving anything, a system based on lying to the people, falsifying their will and turning them into servants of the warlords and their empty slogans.”

Thirty-five years later, militias had become political parties, and the diagnosis in the editorial is just as relevant.

According to Slaiby, unions affiliated with the Lebanese Communist Party were the most organized. In the lead-up to the general strike, they established committees and subcommittees in Beirut’s neighborhoods and across the country to coordinate actions.

The National Federation of Worker and Employee Trade Unions in Lebanon (FENASOL), among other workers' organizations, supported “the formation of popular and syndical committees for organizing the strike,” Keyrouz says.

“Their leaders went to factories, [workers’] homes, and companies all across the country, in the rural areas, to activate participation [in the strike] and highlight its importance,” according to Keyrouz’ crisp retelling.

Braving the Barricades

On the morning of Thursday, November 5, 1987 the country came to a standstill.

The airport and the Port of Beirut shut down, as did schools, businesses, banks, restaurants, and government offices across the country. Newspapers, right- and left- wing, closed for two days to support the strike, and only bakeries, hospitals, and pharmacies remained open.

By all accounts, workers en masse honored the picket line.

Two days later, Assafir resumed publishing, reporting that strike participation was pervasive across sectors and in different parts of the country.

Taxi drivers, agricultural workers in the South and the Beqaa, and municipal employees in Beirut, Zahle and Saida, among other labor groups, began a work stoppage.

“The movement was countrywide, distributed across many areas,” Slaiby relays what he remembers of that first day. “No one could have anticipated or known that there would be this many people participating.” This was, afterall, “a time of violence and war.”

By all accounts, workers en masse honored the picket line.

Most newspapers shut down for two days in solidarity with the general strike. On November 7, 1987, Assafir resumed publication, publishing photos of empty streets throughout the country.

The late journalist Issam al-Jurdi evoked the feeling of optimism in the air. On November 8, 1987, he described in Assafir how the general strike “has caused the sealed dams of sectarianism where despotic militias had ruled to collapse, bringing together [instead] people, all the people, around a national cause that is non-sectarian.”

On Monday November 9, the fifth day of the strike, the GCWL and the various groups and organizations that took part in the second conference held a massive protest at the National Museum.

They organized two marches, one that began from “East Beirut” and the other from “West Beirut.” As the marches progressed, they gathered more and more workers before they finally merged at the museum, a symbolic meeting ground on the demarcation line.

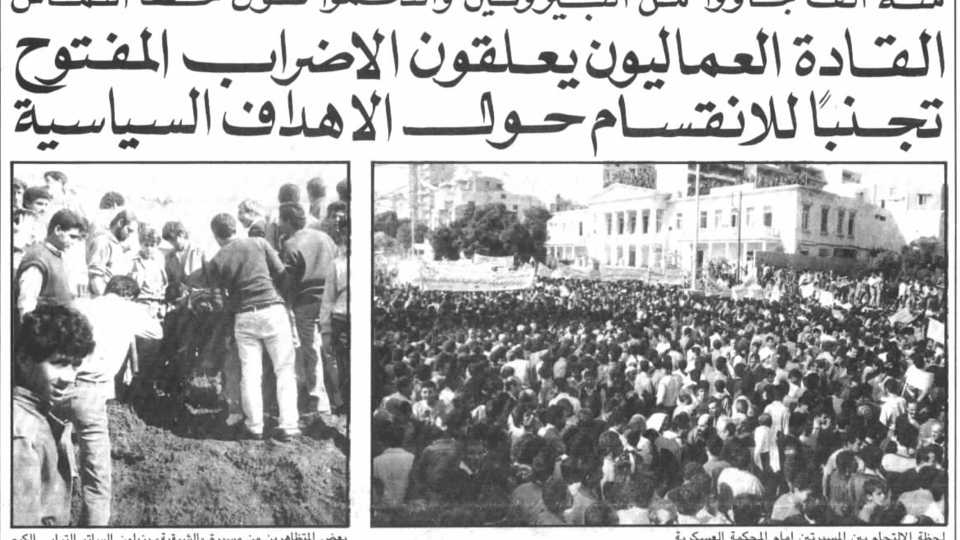

Looking back on the march, Bou Habib remembers how “workers removed the barricades separating the two parts [of Beirut] with their shovels.”

While numbers are difficult to verify, al-Jurdi later reported in Assafir that “hundreds of thousands [...] came out in droves to the National Museum, breaking the barricades and the sectarian barriers, united by one cause: democracy and bread.”

“Some of our syndical colleagues in the eastern part of Beirut were threatened and subjected to intimidation. The militiamen threatened to shoot them. As for us, in the western part, we met in Cola and were also threatened by the militias,” Bou Habib thinks back to the conversations before the museum that day.

Slaiby recalls a similar story. “We were crossing sandbag barriers that had been placed by both sides between East and West Beirut. Whenever we crossed these demarcation lines, militiamen were everywhere.”

“I was walking in the front rows,” he continues. “We were scared and could not know whether we were going to get shot.”

“We were crossing sandbag barriers that had been placed by both sides between East and West Beirut. Whenever we crossed these demarcation lines, militiamen were everywhere... We were scared and could not know whether we were going to get shot.” —Ghassan Slaiby, sociologist

Despite fear and intimidation, there was a perceived sense of safety in numbers. “[All the militias] were against the movement and threatened to shoot us. But because the protest was so massive, no one dared,” according to Bou Habib.

“I participated in the major protest [on the fifth day of the general strike],” Keyrouz reminisces. “I was excited. I felt that this protest was useful… It was a stand against the authorities, a stand against the war.”

However, despite all the enthusiasm that was generated, at the end of the day, leaders of the GCWL convened and decided to suspend the strike.

All in all, the general strike lasted only five days.

The Elephant in the Room

“If you were watching from afar, you’d think that after a protest of this magnitude, no way should a strike like this end or die down. On the contrary, [the protest] should give it a push, right?” Slaiby adds.

“It appears that the GCWL’s strike is just a shout in the void,” Assafir foretold in an editorial published on the third day of the strike.

Apart from a shell of a government with a president not even in the country (president Amin Gemayel was in Amman attending the Arab League summit), there was no "side" with whom to negotiate demands, so the strike had little influence.

“Unfortunately, the very same night of the protest, the GCWL met and announced the end of the strike,” Slaiby says regrettably.

Assafir reported that GCWL leaders met then-prime minister Salim Al-Hoss on November 8 and 9, 1987.

Together, they decided that a technocratic commission representing the prime minister’s office, the Central Bank, and the GCWL would be formed to devise monetary policies that would halt the Lira’s depreciation. The government also promised to allocate public funds toward transportation, housing, and education.

The Lira’s depreciation soon stabilized, only to plunge again in September 1988 with the end of Amin Gemayel’s presidency and the emergence of two governments competing for legitimacy. As for the war — against which the workers had literally put their lives on the line — it was the elephant in the room.

The threat of militarized violence pressured the GCWL to end the strike and concede key demands. Slaiby goes straight to the point. “[The GCWL] was unable to continue and face the pressures that had begun to emerge on the fifth day… There was an essential macro problem that did not allow us to achieve anything… the war!”

Chronicling the war, Traboulsi records that its final years had been some of the most brutal in the whole fifteen-year tragedy.

He describes, for instance, how the so-called “war of liberation” (1989-90), waged by army commander Michel Aoun, left “another thousand killed, thousands more injured, a third of the population transformed into refugees, and the worst destruction and damage the country ha[d] suffered since 1975.”

Warfare in the late eighties impeded political mobilizations and demonstrations.

“Simply put, [the militias] told the GCWL to stop. Those who wanted to continue [the strike] needed to have some sort of strategy for confronting the armed militias, [as] it was no longer as simple as a general strike… If you planned on continuing, you needed to know how to face violence. [The GCWL] was not ready, there was no preparation,” Slaiby says with hindsight.

As expected, the GCWL would draw large participation again from its countrywide base of workers in the immediate years after the war. In May 1992, a general strike, widely believed to have been infiltrated by the partisans of former warlords, toppled the post-war government of Omar Karameh. Formed in a hurry, the cabinet of his successor, Rashid Al-Sulh, prepared for the first parliamentary elections since 1972. Later that year, in September, the postwar spoils-sharing system was born, with Rafik Hariri at the helm of its executive branch.

A Confederation of Workers Without… Workers?

The co-optation of the labor movement in the post-war era is a well-known story by now. With the state and the labor ministry under their control, the warlords licensed in the nineties sectarian shell unions and federations to gradually take over the GCWL.

“These new federations were established not out of concern for workers’ issues, but for political motivations,” according to Bou Habib.

Slaiby perceives that the co-optation and sectarianization of the GCWL is the reason why the confederation was wholly absent from the October 17 uprising.

“It’s not just that it didn’t play a role. [The GCWL] was against the uprising!” The absence of an organized labor movement “was a big weakness for the uprising.”

Bou Habib echoes a similar sentiment. “When we reached October 17, 2019, people protested in the streets, but there was no leadership, no dynamo! The political establishment managed to break the GCWL, the dynamo that united the workers and the people.”

“When we reached October 17, 2019, people protested in the streets, but there was no leadership, no dynamo! The political establishment managed to break the GCWL, the dynamo that united the workers and the people.” —Adib Bou Habib, former head of the GCWL’s Council of Representatives

Besides the co-optation of the GCWL, the nineties also witnessed the gradual transformation of the Lebanese economy and its workforce. The agricultural and industrial workers who were the backbone of the GCWL before the war endured the evisceration of their sectors.

According to sociologist Rima Majed, up until the 1990s, “Lebanon had a local clothes manufacturing industry… [notably] in Bab Al Tabbaneh and Jabal Mohsen.”

Today, this sector “is almost nonexistent,” following “the neoliberal policies of the [Rafik] Hariri era which led to more financialization of the economy, a more services-oriented economy with very little investment or interest in the productive sectors,” she tells The Public Source.

Much of the workforce has been pushed to work in the informal sector. In 2010, it was estimated that 56 percent of all workers were working informally. Majed estimates that “today, most workers in Lebanon work in the informal sector.”

These workers, many of whom are migrants and refugees, can neither join an established union nor legally form their own.

But also, close to 98 percent of all businesses in Lebanon are small and medium enterprises. Without union power, their workers have little leverage against the employers who can “fire and replace them easily,” Majed explains, given the “large supply of workers” and the limited number of new jobs created every year.

On the left, workers removing sand barricades separating the divided capital. On the right, the two marches converge at the Military Tribunal, near Sodeco. Assafir, November 10, 1987.

The majority of the workers in the country — both in the formal and informal economies — are precarious. Structural transformations within the economy have turned them into a surplus population navigating a climate hostile to organizing, confronting legal hurdles toward unionizing.

But Lebanon is not exceptional. Majed explains how “globally today, and particularly with the rise of the gig economy, practically everyone is in a precarious situation. Few are the countries where there is job security like before.”

“The only tool,” she says, “the only real power in the hands of workers is the general strike. But in Lebanon, this tool is co-opted.”

Indeed, the GCWL has become a confederation without workers, if not against them. Its president sweet talks vile oligarchs while thanking sectarian parties for supporting GCWL “strikes.”

The November 1987 general strike might not have been able to achieve its objectives — not least because the war had a purpose and had to continue. But its inspiring bravery is a reminder that in life-and-death circumstances, collective action is inevitable.

Having been close to the labor movement through its ebbs and flows, Keyrouz is resolute. “We must keep on working hard and strategically, and devise a real program for change. Change doesn’t come easily. We need to organize.”

Today, the labor movement faces the momentous challenge to organize under the umbrella of precarious work whose workers have been carrying the weight of this neoliberal political-order on their backs since the nineties.

This organizing means overcoming the perceived hierarchies between fulltime, unionized labor and casual, non-unionized workers. It also requires cutting through divisive differentiation schemes, like sectarianism, sexism and the different racisms, building coalitions between different labor groups, and coordinating actions in solidarity for greater gains.

On August 31, 2021, we saw how organizing around precarious work brought together Syrian and Lebanese truck drivers who blocked the entryways of the Port of Beirut for a wage increase. This organizing approach makes it possible to imagine yet unrealized scenarios of solidarity.

Imagine these same truck drivers blocking the roads around RAMCO two years ago to support Bangladeshi and Indian waste workers, their striking comrades. Then imagine RAMCO workers refusing to collect trash from the port in meaningful, reciprocal solidarity with their comrades in struggle.

Scenarios of solidarity abound in radical imagination. The struggle is long and fraught with danger. But these are the stakes.

—Additional reporting by Christina Cavalcanti.