Are the People to Blame? Debunking Counter-Revolutionary & Culturalist Arguments

Day 102: Sunday, January 26, 2020

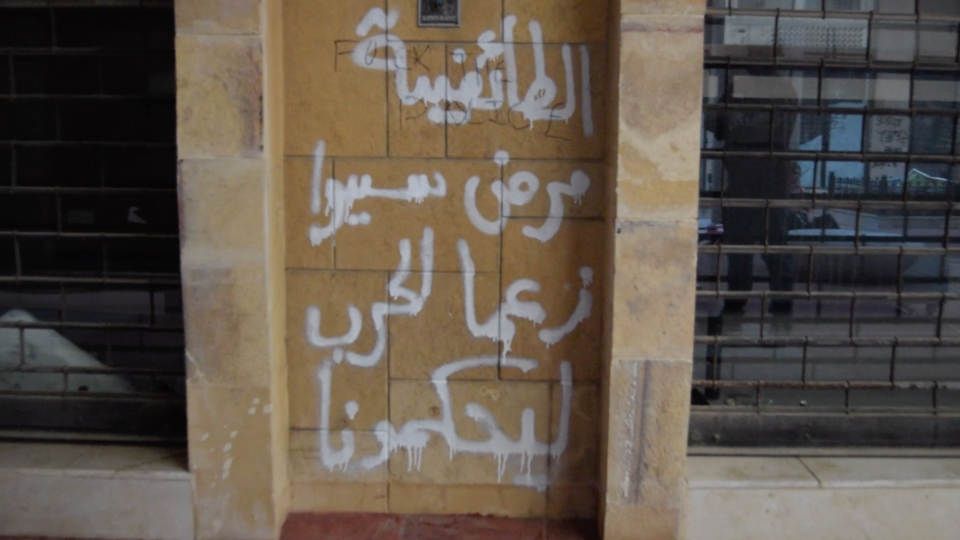

Since the onset of the October 17 uprising, protesters have been met by the establishment’s familiar counter-revolutionary mechanisms: violence, cooptation, repression, fearmongering, and sectarianization. A less discussed means of undermining the popular movement involves rhetorical mechanisms, which originate just as much from the movement’s supporters as from its detractors.

A common talking point that damages the revolutionary momentum — as well as our ability to imagine an alternative Lebanon — revolves around citizens’ agency (or rather, the lack thereof), particularly when it comes to the ballot box. Elections have been brought up in different ways on social media, both by the uprising’s supporters and its critics.

Some argue that if citizens were truly ready to move on from this ruling class, they would have elected better representatives in the most recent elections:

“The last elections in Lebanon took place in May 2018, and the people brought in the current MPs and party representatives. If they wanted change, they would have chosen better MPs.”

Others are adamant that holding early parliamentary elections will only lead to the reelection of the same political class, due to inherently entrenched sectarian identities.

“Let’s be honest, unfortunately we are sheep who will reelect the same corrupt politicians.”

"Unfortunately, sectarianism is a doctrine firmly anchored in the Lebanese persona, and the true curse of the Lebanese people.”

Another subset even questions the compatibility between Lebanese citizens and political change, arguing that their backwardness makes them unworthy of a revolution and a participatory democratic system.

“I am still seeing people throwing trash and paper on the ground… Are such people even fit to undertake reform?”

By shifting the blame for failed governance from the establishment to the citizenry, arguments that question the agency, intelligence, and independent character of the Lebanese people are rooted in misconceptions as well as an internalized inferiority complex — both of which must be unpacked in order to respond to counter-revolutionary tropes.

Lebanon as Electoral Authoritarianism

Is it fair to hold Lebanese citizens accountable for reelecting rulers who have repeatedly failed to meet their needs and expectations? Any attempt at an answer must begin not with unfounded attacks on individuals’ agency and intelligence, but with political and socioeconomic realities. In doing so, we find that the main culprit for elections failing as a vehicle for change is no other than the establishment itself.

The electoral system in Lebanon should be regarded as an example of electoral authoritarianism, a type of system that offers a semblance of democratic institutions but, in reality, is pervaded by practices that undermine the legitimacy of the vote and are intended to reproduce the status-quo.

The 2018 law was designed to reinforce sectarian divisions through gerrymandering, undermine proportionality through the preferential vote, and benefit establishment parties through the manner by which lists are formed and ballots are counted.For one, the electoral system undergirded by a sectarian political economy that has entrenched material dependencies on patrons. Here, we must adopt a broad definition of “vote-buying,” one that goes beyond direct cash transactions prior to election-day, in order to understand the extent to which economic precarity impacts electoral behavior. Decades of sectarian apportionment (muhassassa) and a neoliberal disregard of the role of the state in providing basic services, further enabled by a 15-year civil war, led to the creation of deep clientelistic networks to secure all kinds of services – from jobs and education to facilitating legal services and accessing healthcare. The nefarious relationships this political economy creates between citizens and politicians are particularly exploited during the electoral season. While most of these services are provided informally, we can also trace them through the spike in public sector hiring months prior to the 2018 parliamentary elections. Studies based on surveys with voters also confirm the prevalence of vote-buying.

The electoral law itself also limits the potential for elections to bring real change. The 2018 law was designed to reinforce sectarian divisions through gerrymandering, undermine proportionality through the preferential vote, and benefit establishment parties through the manner by which lists are formed and ballots are counted. Therefore, and as many reports have attested to, the legitimacy of the vote was undermined at its core.

In addition to these systemic issues, independent groups and candidates in the 2018 elections were also victims of voter intimidation, attacks on offices and candidates, and manipulations during vote-counting. Indeed, progressive anti-sectarian actors that could act as alternatives to the ruling establishment have been subject to repression and co-optation for decades.

Another reason as to why citizens keep reelecting the same parties and candidates is precisely because alternatives have not been allowed to emerge nor to develop the capacity needed to wage elections competitively. Whether it be the co-optation of labor unions in the 1990s or the repression of the 2015 movement that rose out of the crisis in waste management, attempts at creating a true opposition have consistently failed to materialize. It is only recently that emerging groups and activists have begun rebuilding networks that would allow them to truly threaten the ruling hegemons – a process which cannot take place overnight.

Why the Self-Hate?

Over 100 days have passed since the start of the decentralized movement, replete with incredible moments of cross-sectarian and cross-geographic solidarity. It is worth asking why, despite the repeated expressions of hope and resilience, so many remain pessimistic about the genuineness of the popular mobilizations and whether we can transcend sectarianism.

Why do so many Lebanese insist on blaming our socioeconomic realities on backwardness (takhalof)? Why is calling citizens “sheep” so normalized? Why do so many Lebanese insist on blaming our socioeconomic realities on backwardness (takhalof)? Why is calling citizens “sheep” so normalized? Why is it acceptable to claim that Arabs rebelling against their oppressive regimes must be driven by foreign powers, not by independent agency? Why are so many quick to assert the cultural superiority of the West at the mere sight of people standing in line or throwing trash in garbage cans? These questions matter because together they raise a fundamental one: How is the uprising supposed to bring tangible changes when our imaginaries remain so limited?

While decades of failed policies and disrupted attempts at change are paramount, a substantial portion of the answer also lies in affective motives. This part of the explanation is one that not only applies to the Lebanese, but also to other citizens of the colonized world. Various scholars have addressed what has been called the “colonial mentality,” an internalized inferiority complex resulting from an acquired belief that the cultural values of the West are morally superior to one’s own. In the case of Lebanon, this colonial mindset is also intertwined with trauma resulting from the civil war and the absence of transitional justice and reconciliation. This situation generated unprocessed trauma, likely leading to repressed selves, and a progressive loss of hope in change, which often transfers onto subsequent generations.

Thus far, the October 17 uprising has led to rebuilding previously co-opted networks and institutions and to reigniting a sense of fervor. But it must also become a vehicle for reconciling with our past and embracing our dynamic identities and cultures. In a beautifully written and amusingly witty article, social anthropologist Ghassan Hage writes about “urban jouissance” (joy), in which he celebrates the “outside-the-law” culture of Beirut’s free spaces, encouraging us to rethink their potential admiration of western culture. In one of my favorite quotes, one of his interviewees says:

“I can’t bear the thought of standing in a line, idiotically waiting for my turn to buy a sandwich tasting as bland and sterile as the people who are queuing to buy it. I know how to queue. I don’t want to queue. I know saying this is not supposed to be ‘civilized’. I don’t want to be civilized. I love rubbing shoulders with everyone, trying to squeeze myself in all the way to the counter to buy my man’ousheh. I buy it and it just tastes so good, like I’ve earned it. I’ve never heard of anyone returning home without having bought what they came for just because people push and shove a little bit instead of queue. Queuing is for assholes who don’t need much to think of themselves as refined and ‘advanced’.”

Rather than resorting to familiar counter-revolutionary and self-defeating tropes to validate our own fears and anxieties, let us instead remember the warmth and solidarity felt on the streets as we come together to share, heal, and transcend in moments of doubt.I use this anecdote not to celebrate all versions of the lack of order or efficiency in Lebanon, but in the hopes of triggering a shift away from the colonially-driven “civilized vs. uncivilized” binary — to encourage us to think more broadly and collectively of what an alternative Lebanon might look like. One that pauses to embrace rather than immediately disdain what Hage refers to as shatara — “being clever and skillful at maneuvering oneself inside and outside existing structures and regulations” — which manifests in everyday practices such as driving, navigating bureaucracy, and kinship. Rather than resorting to familiar counter-revolutionary and self-defeating tropes to validate our own fears and anxieties, let us instead remember the warmth and solidarity felt on the streets as we come together to share, heal, and transcend in moments of doubt.