Beirut’s Blasted Neighborhoods: Between Recovery Efforts and Real Estate Interests

Reactions to the explosion of the Port of Beirut have sounded the alarm of permanent displacement, and fingers are already pointing to predatory real-estate developments that could accelerate the process. On September 30, parliament passed measures that it claims will halt the land grabbing of properties owned by residents affected by the blast. But what is fundamentally missing from this seemingly caring narrative is the history of large waves of evictions over many decades in districts such as Geitawi, Mar Mikhael, or Gemmayzeh. Rather than an interruption or a new turn in the occupation of the neighborhoods forming these districts, we argue that the blast should be seen as a disruption that will intensify the effects of the already-in-place mechanisms, pushing away a larger number of those who have worked or lived in the neighborhoods surrounding the port. Therefore, if the architects of Beirut’s recovery are serious about bringing people back, then they must address the structural and institutional forces that triggered trends of displacement well before the blast.

The first waves of displacement (1996-2008) in these affected neighborhoods fall neatly under gentrification trends, which are processes of urban transformation through the influx of more affluent residents and businesses.

Pre-Blast Urban Development Trends

The first waves of displacement (1996-2008) in these affected neighborhoods fall neatly under gentrification trends, which are processes of urban transformation through the influx of more affluent residents and businesses.6 A handful of developers who identified real-estate opportunities in these neighborhoods were the first to trigger gentrification in the early 1990s. Some of these developers were investment companies influenced by the nearby redevelopment of Beirut’s historical district by the real-estate private company Solidere, on the western edge of the blasted neighborhoods. Others were landowners redeveloping their own property. As of 2009, cultural and entertainment classes contributed to a rapid acceleration of development trends, as these classes found in the historical character of the built environment and its walkable scale an ideal setting for nightlife and creative industries.7 Tensions over the day and night uses of the districts eventually intensified, and while the better-off residents of Gemmayzeh succeeded in tempering loud entertainment activities, those in Mar Mikhael had to either cope with the nuisances or leave. The lucrative profits generated by these businesses and the higher purchasing power of the tenants they attracted produced negative consequences for the residents. They widened the rent gap and further incentivized landlords to terminate old rental protections, which eventually accelerated evictions.

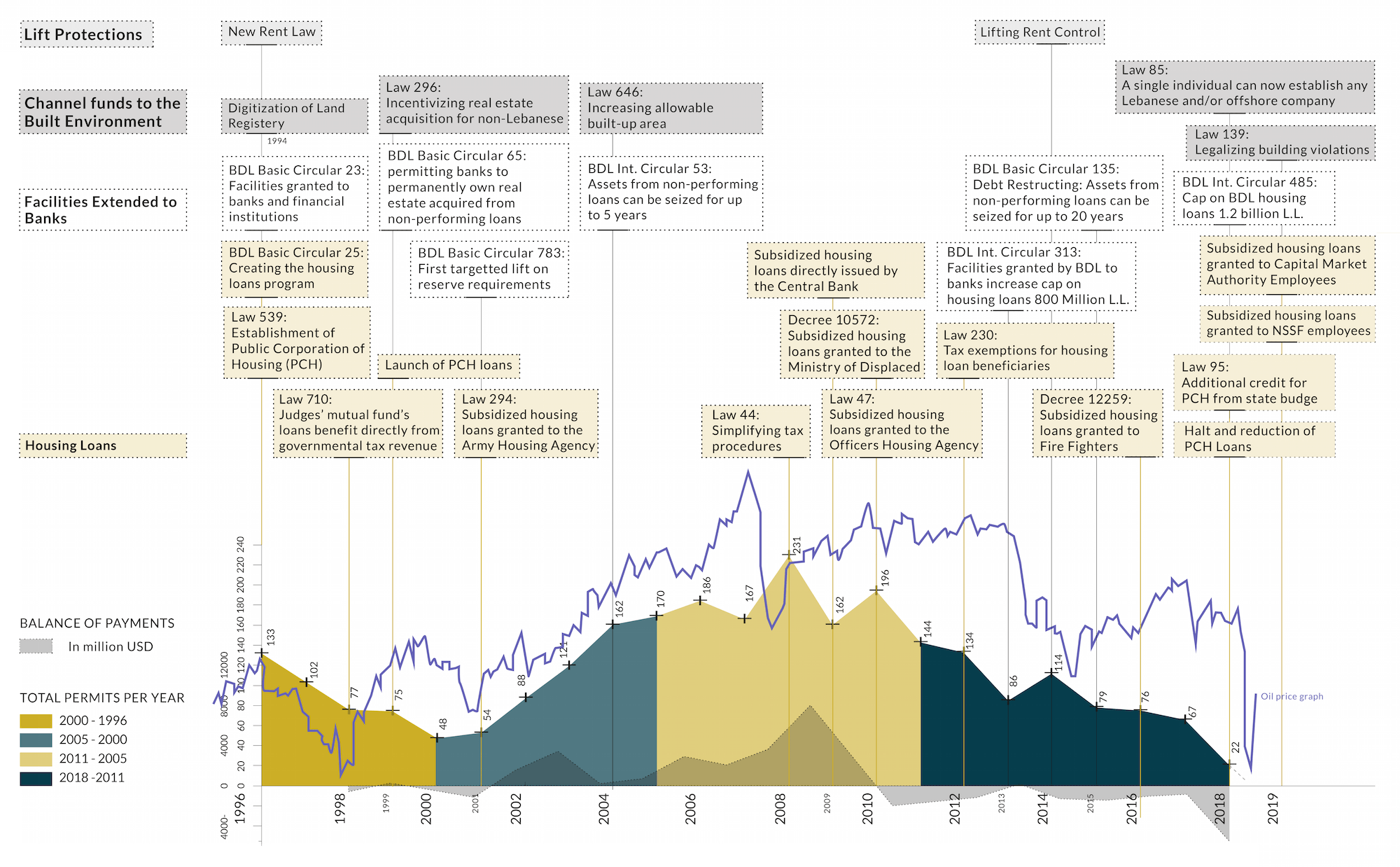

A second, more alarming trigger for evictions and displacement stems from the subjugation of the land market to financial interests. This process is well in line with the current phase of global neoliberalism, sometimes labeled as financialization. By relying on land transactions to attract foreign capital, Lebanese decision-makers have favored the role of the land as a financial asset over its other functions as a shelter or workplace. Our research reveals that between 1999 and 2011, at least a dozen laws were issued to incentivize the flow of capital into the built environment (Figure 1).

A second, more alarming trigger for evictions and displacement stems from the subjugation of the land market to financial interests. This process is well in line with the current phase of global neoliberalism, sometimes labeled as financialization.

Thus, property laws were modified to facilitate its purchase by foreigners and property registration taxes were reduced. In parallel, urban and building regulations were modified to intensify construction and increase profit for developers (Figure 1). In addition, the Central Bank issued multiple circulars to ease its reserve requirements in order to facilitate the provision of housing mortgages, and lifted restrictions that previously prevented banks from investing directly in real-estate (Figure 1). Until 2019, when the financial crisis unfolded, the parliament was still ratifying agreements and expanding the provision of housing loans, targeting additional public sector employees like judges and members of the police force. Despite the alarming signs of the financial crisis and the depletion of the banks’ reserve requirements, therefore the life-savings of the depositors, the Central Bank continued to ratify protocols to expand the number of public institutions subsidizing housing loans (Figure 1). The consequences of these financialization strategies are well known: old buildings were replaced with higher and denser buildings that are mostly vacant, while empty apartments became the equivalent of safety deposit boxes rather than homes for living. This practice further intensified after the October 2019 meltdown, as large depositors began to look for safe assets to park their capital.

Figure 1: Intensifying construction through financial incentives, housing loans and building regulations

An Uneven Housing Policy Framework

Meanwhile, one should recall that there is no framework of housing policy-making that champions the right to housing in Lebanon. Instead, the Ministry of Housing was dismantled in 1996 and replaced (tellingly) by the Public Housing Corporation (PHC). The latter limited its interventions in the housing sector to the disbursement of housing loans as the supposedly affordable housing scheme for Lebanon. Not only were these policies counterproductive to affordability, but they also could not compensate for the absence of rental regulations, incentives for affordable developments, or other housing policies needed to introduce a substantive framework of housing policies. Additionally, since 1992, rent was fully liberalized maintaining only a small segment of society protected by old rent control. This protection became a concession to the old tenants’ vocal mobilization – rather than a vulnerability assessment or a recognition of housing as a right. It was consequently always maintained as a negotiated concession and not a long term housing security.

[T]here is no framework of housing policy-making that champions the right to housing in Lebanon. Instead, the Ministry of Housing was dismantled in 1996 and replaced (tellingly) by the Public Housing Corporation (PHC).

To make matters worse, the half-baked new rental law that was issued in 2014 came to dismantle rent control with provisions that were never implemented.6 Consequently, the law turned the right to housing into a private feud between landlords and tenants who had no other choice but to challenge each other’s claims in courts. Meanwhile, the liberalized rent has placed numerous tenants in challenging conditions, as landlords are enticed to demand exorbitant rents whenever they can because of the skyrocketing value of land. With the Lebanese pound crumbling after 25 years of pegging to the dollar, agreements over the actual rate of rents, often signed in US Dollar, have led many tenants to leave, while others are caught in endless negotiations around the rate to use and the jurisdiction to trust.

The Development Machine and Beirut’s Blasted Districts

Monot, Mar Mikhael, Gemmayze, Geitawi and Karantina, neighborhoods identified as severely affected by the blast, were heavily impacted by these trends. The Beirut Urban Lab 2018 survey identified four banks and 13 investment companies that are heavily involved in the construction activity in these districts. Commercial registry records show that the shareholders of these companies operate through special purpose vehicles, offshore companies, and such holdings as Solidere or Biel. Most of these investors either have strong connections to the political and banking classes, or are themselves politicians and bankers. Wealthy Lebanese expatriates and foreign nationals, primarily settled in the Arab Gulf, also figure prominently among influential investors.

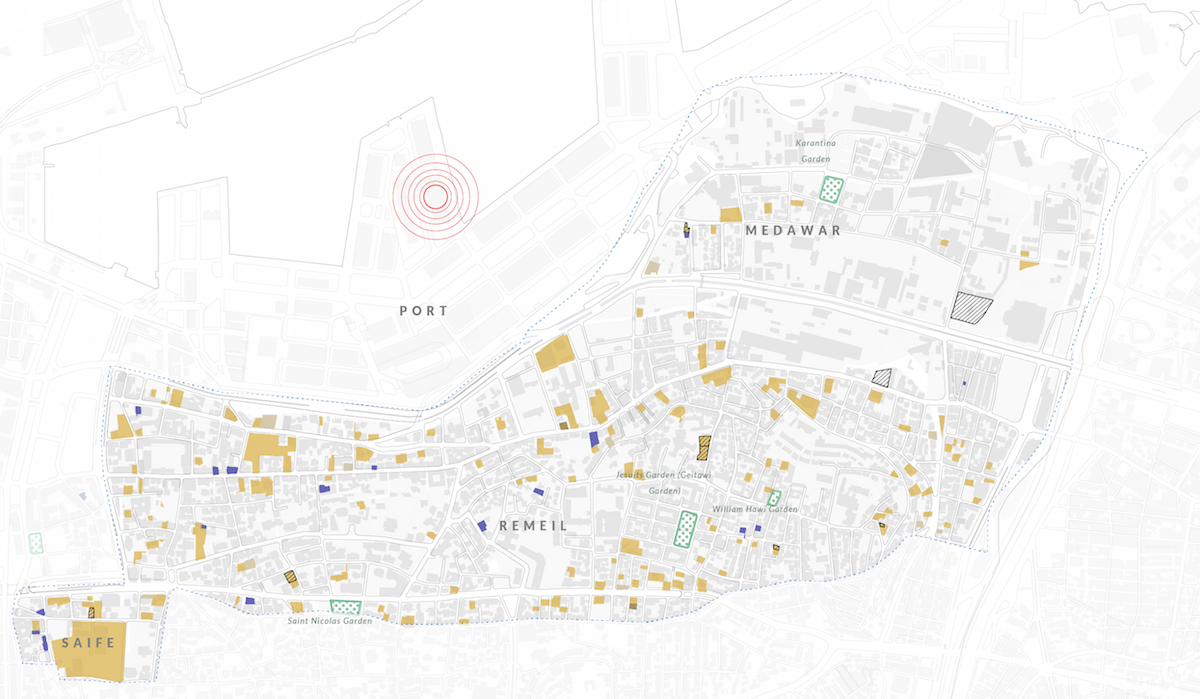

In parallel to the intensive building activities, the survey identifies very high vacancy rates in these neighborhoods, varying between 20 and 50 percent of new developments. Hundreds of recently built apartments were empty while developers were evicting residents (Figure 2). These evictions were further triggered by new construction activities as of 2014, when the real-estate crisis unfolded. Thus, developers either left many empty buildings, or turned evacuated buildings into parking lots, their development prospects unfulfilled (Figure 2).7 At the time of the survey, another 10 buildings were still standing, as residents resisted eviction after developers purchased the buildings where they dwelled.8

Figure 2: Pre-blast forced displacements in neighborhoods affected by the blast

-

Explosion Site

-

Assessment Zone

-

Demolition Permits (2005 to 2017)

-

Empty Lots*

-

Parking Lots*

-

Green Spaces*

-

Evicted/under threat of Eviction*

The recent building activities had also attracted new residents. In the districts under discussion, almost 200 households had benefited from mortgages subsidized by the PCH. Many among them face the threat of eviction as they struggle to pay back their loans. As poverty and unemployment soar (the World Bank sets the latter at around 50 percent), we expect that households who had sought homeownership as a measure of security will become more vulnerable, despite the PCH’s ongoing efforts to temporarily halt evictions. Interviews we conducted with young professionals who have worked or resided in these districts indicate that they also bore the consequences of difficult rent negotiations. Many related that they were ready to leave following accumulating negative experiences with their landlords, while others had reached a compromise, fixing units in lieu of rent.

In order to change the tides, we need to approach urban recovery by challenging the historical forces that have led to evictions, both in these districts and beyond them in the city.

Post-Disaster Recovery: An Integrated Framework

In closing, it is important to return to the question of recovery following a disaster. While the demolition of apartments, buildings and livelihoods are substantial, it is undeniable that the long-term devastation, particularly in terms of population displacement and economic loss, precedes the explosion. In order to change the tides, we need to approach urban recovery by challenging the historical forces that have led to evictions, both in these districts and beyond them in the city. If urban recovery falls short of addressing root causes, then it is likely that more people will succumb to eviction; heritage will continue to crumble; apartments will remain vacant; and the economic vitality of these districts will dwindle. An inclusive and people-centered urban recovery strategy begins by reclaiming the right to housing and the city. It is a right to dream and enact urban alternatives, futures that are neither dictated by greed, nor managed by corrupt political orders. The dream is still far, and the pathways to reach it are complicated. Yet activists and other stakeholders who are committed to rebuilding Beirut on new foundations will need to incorporate within their discourses and imaginaries an understanding of how the city was hijacked by real-estate investors over decades of poor governance. More than anything, however, recovery requires a new model for governing housing, one that works in the interest of people rather than the private interests of the ruling political class which has, for the last three decades, subjected the city and its housing sector to a narrow, profit-based urban vision.

Map Credits: Beirut Urban Lab Critical Mapping Team, 2020