Warm Winter Woes: How Global Warming is Affecting Local Agriculture and Food

Marcelle Slim’s almond and plum trees burgeoned early in her orchards in Jezzine this year, amid an unusually warm winter. But when a February storm followed a sunny January, a hail storm destroyed buds on the trees, and irreversibly cost her the fruits they were yet to bear.

“The flowers of the plum and almond trees went to waste. It means that this year, we will not have any harvest from these trees,” Slim told The Public Source in March. A retired school teacher, she has been tending to her family's orchards and garden for 15 years. This winter, she noticed that rain and snow were late, which disrupted her plowing and planting schedule.

“Usually, we plough in January. But the storm came, and we were late to plough, so weeds grew really tall in the orchard,” she said. This means a delay in sowing and harvesting. This winter has been particularly dry in Lebanon, with only a couple of sparse storms in February and April. Slim had to water parched crops that are usually rainfed, such as garlic and onions, to make sure they survive.

Lebanon is starting to experience a shift in seasonal events — spring warmth came early and was followed by winter-like storms in April.

Slim’s woes are one example of the impact of global warming, and a sign of what’s to come as Lebanon and the Eastern Mediterranean heats up faster than anywhere else on the globe. This means a looming threat of drying rivers and rising sea levels, scarce but intense floods and storms, scorching heat, drought, wildfires, an existential threat to flora, fauna, and to the very habitability of the region.

Salem al-Azwaq picks a few leaves of lavender to smell them. He specializes in aromatic herbs and fruit trees. Al Marj, Lebanon. April 14, 2023. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Lebanon is starting to experience a shift in seasonal events — spring warmth came early and was followed by winter-like storms in April. This shift has been gradually happening for decades, two to five days at a time. The mistiming of warm days and rain disrupts many natural cycles that are interdependent — such as when flowers bloom, when bees pollinate, when birds migrate, and when mammals come out of hibernation. Like the gears of a clock, one missed beat is felt across the whole ecosystem.

With less rain, higher temperatures, and mistimed seasons, both the natural world and agriculture is at risk. This means our food security as well as our ecosystems are on the line.

This Year’s Rain: Scarce and Late

On a sunny April afternoon, just one day after it had rained, Salem al-Azwaq checked the moisture around a patch of aromatic plants. “Look, it’s dry,” he said, rubbing the soil in his calloused hand. If it doesn’t rain from December through January — and it didn’t this year— the ground will not store enough moisture for the summer, he explained. He is one of many farmers to worry that this winter did not provide enough rain and snow to replenish Lebanon’s water reserves.

Marc Wehaibe, the head of Lebanon’s Meteorological Department, told The Public Source that winter 2022-2023 was marked by a shortage of rain. By the end of January, it had only rained a total of 285.8mm, below the minimum average rainfall for that period.

Wehaibe’s team analyzed historical data going back to the 1930s, and they noticed that over the past century Lebanon witnessed ten years of rainfall shortage. In the majority of years when it rains less than 330mm by the end of January, it will not rain much in later months, a signal for an overall shortage of precipitation for the year.

With less rain, higher temperatures, and mistimed seasons, both the natural world and agriculture is at risk. This means our food security as well as our ecosystems are on the line.

At the time of going to press, the total rainfall for winter 2022-2023 was 648.4mm, well short of average rainfall that ranges between 700mm and 1000mm. However, according to Wehaibe, this “normal average” has been dropping over the past three decades.

“It is climate change and it is related to the greenhouse effect,” Wehaibe said. The greenhouse effect is when heat is trapped in the atmosphere by gasses such as carbon dioxide, methane, nitrogen oxide, and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). The gasses cause the global temperatures to rise, which disrupts weather patterns, heats the oceans and sows chaos in ecological systems.

Farmer Kassem al-Zo‘obi stands over a small pond that is used for watering vegetables. He fears that the water will run out before the end of summer. Saadnayel, Lebanon. April 14, 2023. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Patterns in decreasing rainfalls will likely worsen. Rainfall in the Mediterranean is expected to drop by 20 percent over the next 20 years, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the United Nations body that monitors climate change.

In addition to less rain, the schedule of the seasons has also been shifting. Raed Zeidan, a farmer and agriculture educator in the Chouf, told The Public Source that the delay in rain is apparent. Zeidan explained that Eid el Salib, celebrated on September 14, usually marks the first showers in Lebanon’s mountains. “We haven’t seen rain around that time in the past few years.” Instead, in 2022, the first rain came in late November, more than two months late. In parallel, it continued to fall in April when it should have stopped in March.

This shift in seasonality means that winter has been starting later and extending into spring, explained George Mitri, director of the Land and Natural Resources Program at the University of Balamand. Mitri said that his research also points to a rise in drought conditions, with persistent dry and hot weather.

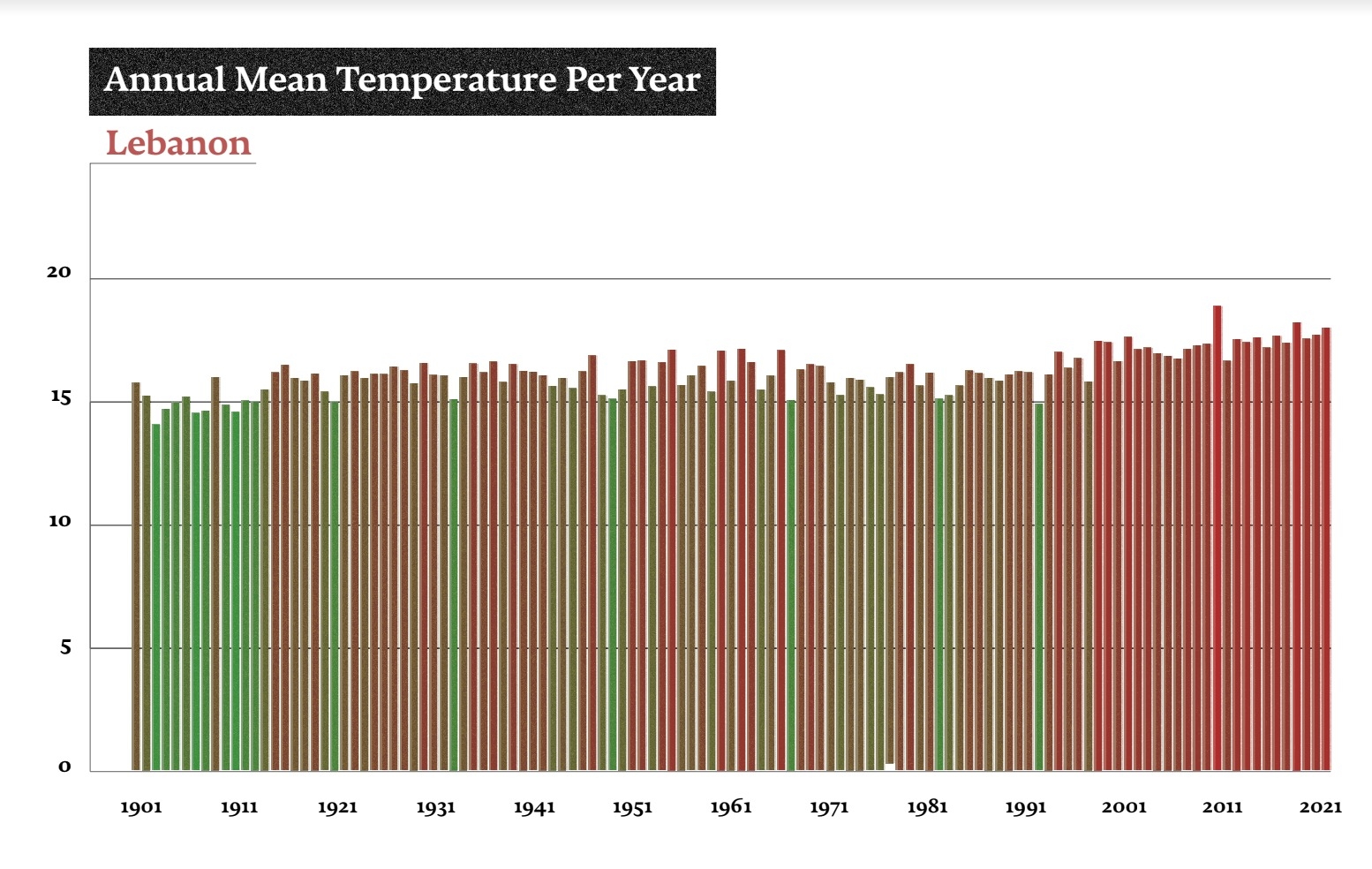

A bar graph shows the gradual increase in annual mean temperature in Lebanon from 1901 to 2021. For each year, the average temperature was color-coded with a gradient that goes from green for lower temperatures to red for higher temperatures. (World Bank Climate Portal).

Farmers in the Bekaa who used to dig wells to water their crops have witnessed the impact of decreasing rainfall first hand. Over the past few decades, they have had to dig almost three times deeper to reach the water table, many told The Public Source.

“The impact is clear in pests outbreaks, fires, and land degradation,” said Mitri, who studies the effect of droughts on the country’s mountains and forests. “These are the results of climatic changes.”

Why This Matters

Less rain will put an intense pressure on agriculture — 70 percent of which is rainfed. According to a 2022 study published by the World Health Organization and the American University of Beirut, “changes in climate will most likely negatively affect yields, as well as the quality and diversity of both wild and cultivated food products.”

Wheat is one of the most crucial rainfed crops that might be affected this year. Amani Dagher, an agroecology trainer and consultant with permaculture association SOILS, warns that wheat yield might be low with late harvest this year. “I heard that in the Bekaa, because there were 30 days of warmth and no rain, wheat grew very slowly.” However, farmers who can afford to use water sprinklers might be able to maintain a better yield.

Wild plants are another category of food that are not only rainfed but are exclusively reliant on rain for regeneration. During very dry winters some wild grasses do not grow at all. This years’ storms destroyed the grasses that did, the same way Slim’s plum and almond harvests perished.

Souhaila Massoud Ghanem is a forager who searches out wild edible plants. She said that, “Herbs such as dardar (Star Thistle), and qors‘anneh (Eryngo) were damaged by the frost. Because it was hot, the plants burgeoned early so when the cold weather came, they boiled, as if you poured hot water on them.”

The apricot trees at Mohamad Salman al-Dayqa’s orchards are starting to bear fruit. His neighbor Abou Talal said that his trees lost their burgeons after the unexpected cold storm in mid-April. Hizzine, Lebanon. April 14, 2023. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Wild herbs are resilient and can sprout again this spring, but trees that lost their buds to hail and cold will not bear fruit this summer. The trees most affected are those of the prunus family, such as plums, peaches, and almonds. Dagher said that some apple and pear trees could face a similar fate if it snows when they first flower.

Salem al-Azwaq, a 43-year-old farmer who specializes in fruit trees, said that the harm of losing flowers has an impact beyond the harvest. As prunus trees flower early they provide vital nutrients for bees to survive until spring. Without these flowers, bees and other insects could starve, and without pollinators, other trees will not fruit. “Together, they form a complete circle, like prayer beads. If one goes missing, there will be a gap,” al-Azwaq said.

Orchards on high altitudes — such as Slim’s in Jezzine — are the most affected by late storms. Fortunately, in the Bekaa valley where it didn’t snow or get too cold, many trees will still bear fruit this season, farmers told The Public Source. However, Bekaa farmers have seen their vegetable harvest take a hit due to late and scarce rain.

Broad beans and fava beans are largely missing from the market even though we used to get bumper crops by the end of February. Amani Dagher said that most farmers wait for the first rain — usually in September — to soften and dampen the soil so they can prepare it for cultivation. Fava beans are the first to be sowed, and take four to five months to grow. Now, farmers have to wait until December to plough, so winter harvests such as fava beans, cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, and green onions are late to be sowed and harvested. This delays the summer harvest of garlic and melons, among others.

Kassem al-Zo‘obi’s fava bean field is not ready for harvest yet. This year, he is considering selling dried fava beans since his produce will not be ready in time for the fresh market. Saadnayel, Lebanon. April 14, 2023. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

This season, Kassem al-Zo‘obi has sowed his Saadnayel farmland in the central Bekaa with fava beans, spinach, onion, and garlic. None were ready to harvest in April, and all had been irrigated to survive the dry spell. “When it rained the first time, seeds started to grow, but it didn't rain again for a while. We had to water the crops so they wouldn't die.” Vegetable plants give better produce when there is rain and humidity, he added. When it’s hot in the winter, the crops will be in bad shape.

“Those who can’t afford to install sprinklers will be at a loss,” he said, pointing to his neighbor’s land. It is too expensive now to set up these watering systems and fertilize the soil. Luckily, al-Zo‘obi invested in them years ago and has been using organic fertilizers to improve the health of the soil.

The dollarization of goods and devaluation of the local currency makes it harder for farmers to adapt to the shifting seasons and drought.

Alfalfa for cattles, which is usually rainfed, also had to be watered, said agricultural engineer Mohamad Salman al-Dayqa. Otherwise, it grows poorly without water. In parallel, pastures for cattle might also be at risk since they are exclusively rainfed. “If it doesn’t rain enough, pasture land will not be green, and there won’t be enough herbs and plants to feed the animals,” said Dagher.

While farm animals are not directly impacted by the changing climate, according to shepherds interviewed by The Public Source, a lack of fodder could affect their health and their milk production, ultimately impacting another food group.

The Economic Crisis Pours Fuel on Climate Collapse

Lebanon’s unbridled economic collapse is at the forefront of everyone’s mind and its ramifications seep into every struggle — including the mitigation of the climate crisis. The dollarization of goods and devaluation of the local currency makes it harder for farmers to adapt to the shifting seasons and drought.

“We didn’t lose any harvests, but we had to spend a lot of money,” Kassem al-Zo‘obi said. He has been struggling to make ends meet. This winter, he spent millions of Lebanese pounds to buy diesel for water pumps. This is an additional expense; usually, the rain waters his vegetables for free.

Farmers who cannot afford fertilizers, water and electricity might have low yields or underdeveloped produce, ultimately bringing in less profit. Even those lucky enough to secure the conditions for good yields might barely break even in a competitive and loosely regulated market. Customers who are struggling with an ever diminishing purchasing power often opt for underpriced imports. Local farmers are also sometimes barred from exporting because they cannot meet the scale or phytosanitary conditions that are imposed in international markets.

Kassem al-Zo‘obi installed water sprinklers in his spinach field to compensate for the lack of rain. Saadnayel, Lebanon. April 14, 2023. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Al-Zo‘obi has not yet harvested any vegetables to sell, but he is worried about the profit margin. If prices are not adjusted to the skyrocketing dollar, he will not be able to offset the cost of production. This includes land rent and fertilizers that he must pay for in dollars, as well fuel expenses for irrigation pumps and to transport produce to Beirut. Most of his expenses, notably rent, have doubled over the past two years.

“Last year, we broke even. This year, we don’t know yet,” he said in mid-April.

Cultivating Better Futures

Even though the climate prospects are grim, all hope is not lost. Plants adapt and so can we. There are many ancient and modern agricultural practices that can mitigate the impact of global warming and thrive despite the changing natural conditions.

Around the world, farmers have embraced centuries-old practices and agroecology to improve the health of our soils and ecosystems with regenerative practices such as reduced-tillage farming, rainwater harvesting, multi-crop farming, rewilding, and the use of organic fertilizers from animals.

Saving our agriculture, our food, and our lives in the midst of a climate crisis will take a radical re-imagining of our economy and relationship to the land.

Amani Dagher helps farmers adopt sustainable practices. “We need to think about how to maximize the storage of water in the land,” she said. This can be done by collecting rainwater in cement reservoirs or small lakes. Farmers can help the soil store water by plowing less, using no-till machines, and allowing for mulched patches of land that better retain moisture. Dagher explained that farmers can also improve their financial revenue by diversifying their crops and including such animals as chicken and cattle whose waste can replace chemical fertilizers.

“These practices help us adapt to the circumstances that are coming,” Dagher said. “This is only the beginning of what’s to come.”

Saving our agriculture, our food, and our lives in the midst of a climate crisis will take a radical re-imagining of our economy and relationship to the land.

George Mitri, who specializes in the study of forest systems at Balamand University, warned: “We cannot stop climate change at the country level. To the contrary, we are on the receiving end. But what we can do is adapt to increase our resilience. We need to work to make it less catastrophic for our ecosystems.”