Intra Investment Company: The “Lebanese State’s Best Kept Secret”

Editor's Note: The black dots (●) in the text are clickable to display documents sourced in this article.

The fall of Intra Bank in the 1960s has become the stuff of legend. Conspiracy theories have been told and retold to account for why Lebanon’s once-biggest bank wasn’t too big to fail.

Was the liquidity crisis that hit Intra manufactured in the first place? And even if it wasn’t, who spread the rumors that led to a dramatic run on the bank? Why did the Lebanese Central Bank not come to the aid of the country’s biggest bank in its time of need? Was it because its founder Youssef Beidas was Palestinian? Were the Saudis involved? Or was it simply a case of smaller oligarchs banding together to take out the big fish? Even Edward Said (who was a distant relative of Beidas) weighed in, writing in his memoirs that Intra Bank’s “astounding rise and fall was considered by some to presage the terrible Lebanese-Palestinian disputes of the seventies.”

Interest in this financial behemoth has once again been renewed — this time because of the stark contrast between what happened in the 1966 banking crisis and what is happening in our current one.

Then, Intra Bank’s small depositors were compensated in full and the banking system as a whole was reformed. Unable to maintain deregulation in its most extreme form, bankers accepted certain reforms of the financial system. A deposit insurance scheme was established, meant to protect depositors in the future (the National Institute for the Guarantee of Deposits). And two new entities were charged with overseeing banks and even taking them over if they failed (the Banking Control Commission and the Higher Banking Committee).

Now, banks have enjoyed free rein to impose de facto haircuts on most depositors, while oligarchs siphon their wealth abroad. In the years between, the institutions that emerged from the Intra debacle to protect depositors have been neutralized, stacked with cronies of oligarchs.

Fifty years after the collapse of Intra Bank, Intra Investment Company still exists, and the Lebanese state and Central Bank hold majority shares. Yet the public knows close to nothing about Intra.

But beyond the historical contrast — and sidestepping the labyrinth of why exactly Intra Bank collapsed — the legacy of Intra haunts us in a more material sense.

After all, the vast remnants of what was once Intra Bank did not disappear into thin air. Instead, the defunct bank’s profitable assets became Intra Investment Company, a joint-stock company established in 1970 as Lebanon’s largest financial institution.

Fifty years later, Intra Investment Company still exists — and the Lebanese state and Central Bank hold the majority share, 10 and 35 percent respectively. Yet the public knows close to nothing about this entity.

Intra is the “Lebanese state’s best kept secret,” in the words of economist Albert Kostanian.

What exactly does Intra Investment Company own? Where do the profits go? Does it generate any revenue for the state?

Intra could be up for sale if the controversial proposal to privatize state assets gains ground, so the public should know what is up for grabs.

Answering these questions has become crucial in our current crisis.

For one, Intra is among the entities that will be up for sale if the controversial proposal to privatize state assets pushed by Lebanon’s banksters continues to gain ground. The public should know what is up for grabs.

Moreover, as Lebanon’s oligarchs ramp up their calls to privatize state assets through a joint-stock company or a debt-defeasance fund as their solution out of the crisis, here we have the case of an existing private joint-stock company that has been around for 50 years. One whose past and present should chill any enthusiasm for privatization.

A few meters from Ras Beirut’s iconic ‘Red House,’ at the intersection of Abdel Aziz and Souraty streets, stands another building from a bygone era: a 1950s modernist structure that once housed Intra Bank, Lebanon’s largest bank until it collapsed in 1966. Once imposing itself on the city’s skyline, today the building would hardly be noticed by a passerby. Beirut, Lebanon. April 14, 2022. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

The Shady Origins of Intra Investment Company

By the time it collapsed in 1966, Intra Bank was huge. In Lebanon, it controlled almost 50 percent of deposits. One-third of parliamentarians and five ministers reportedly had accounts at the bank.

The bank was also the majority shareholder in key engines of the Lebanese economy, including Middle East Airlines (MEA), Casino du Liban, Société des Grands Hôtels du Liban (which operated the Phoenicia Hotel). It owned shares in the company that was awarded a 30-year concession to operate the Port of Beirut, and companies in the entertainment and audio-visual sector, most notably Studio Baalbeck.

Beyond Lebanon, Intra had branches and subsidiaries in Syria, Iraq, Jordan, the Arab Gulf, Brazil, Liberia and Nigeria. It held prime real estate in Geneva, the Parisian Champs-Élysées, and New York City, where it purchased a skyscraper in Fifth Avenue’s Rockefeller Center, hung a Lebanese flag, and named it House of Lebanon, dreamt up as a hub to direct trade and commerce to Lebanon. Intra also had major foreign investments, including the company that operated the second-largest shipyard in France.

When the bank collapsed, faced with mobilization by small depositors asking for their money, the Lebanese government paid L.L. 50 million to Intra’s small depositors, those with accounts of L.L. 15,000 or less.

But the rest of the salvage operation was more complicated. Not only was the bank a major shareholder in key pillars of the Lebanese economy, but its creditors included the governments of Kuwait, Qatar, and the United States (represented by the US government’s Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC), which had given a loan to Beidas to purchase wheat for the Beirut port grain silos). Saudi investors had already withdrawn all their money by the time the bank collapsed.

The plan for Intra Investment Company was the brainchild of the infamous Roger Tamraz who would later star in some of the most visible local and international corruption episodes of the 80s and 90s.

Rather than sell the rest of the assets via liquidation to pay large depositors, a plan was hatched to convert depositors into shareholders in a new holding company that would be called Intra Investment.

The plan was the brainchild of the infamous Roger Tamraz, who at the time was representing American investment banking firm Kidder, Peabody & Company. Tamraz would go on to star in some of the most visible corruption episodes of the 80s and 90s: first as a well-connected international businessman, later as the “Kataeb’s primary financier,” and eventually as Intra Investment’s most controversial chairman. In 1991, he was formally charged by the Lebanese judiciary with embezzling $200 million through Intra-related activities; in 1997 French courts charged him with “bank fraud, conflict of interest and abuse of trust.”

By 1980, the US had sold its shares in Intra, and the company had sold its real estate in Paris and New York. But Intra was still the majority shareholder in MEA, Casino du Liban, Studio Baalbeck (97.5 percent), Banque Al Mashreq, and the Bank of Kuwait and the Arab World (96.65 percent), to name a few. It was also renting out its vast real estate assets and recording around $7 million in profits per year.

The Intra Bank collapse occupies the entire front page of Lebanon's Annahar newspaper, including a photo of depositors lining up outside a branch. October 16, 1966.

Deciphering the Intra Black Box

We know more about Intra’s ownership, assets, and profits in the 1970s than about its current ones.

In violation of legal requirements, Intra does not publish annual reports or financial statements. The company’s current website is inactive, and former versions are skeletal.

The only official figures Intra releases are in its annual balance sheets in the Official Gazette — but these have been published sporadically, exclude details about the company’s assets, activities, or subsidiaries, and the last publication was in 2008.

By law, Intra like all joint-stock companies must submit financial statements, auditor’s reports, board of directors’ reports and minutes of the general assemblies, among others, to the Commercial Register, which is open to the public. But despite repeated attempts, The Public Source was unable to obtain copies at the Commercial Register.

Two requests for Intra’s 2017 budget by the transparency watchdog Gherbal Initiative were rejected by Intra’s chairman Mohamad Cheaib on the basis that the Access to Information Law does not apply to joint-stock companies operating under the purview of the Code of Commerce. But the Access to Information Law “explicitly states, in Article 2, paragraph 7, that ‘mixed companies’ fall under its purview,” reminds us Mohammad Moghabat, lawyer and senior legal consultant at the Lebanese Transparency Association. “Any private company in which the state owns a share, such as Intra or Middle East Airlines, are considered mixed companies, and the Access to Information law should apply to them,” emphasized Moghabat.

Audits conducted of the Central Bank (BDL) in 2018 by Deloitte and Ernst & Young, and leaked anonymously in 2020, “were unable to ascertain the value of [BDL’s] investment in an associate [Intra Investment Company]” due to the “unavailability of financial and other relevant information to perform such an assessment.”

Even Intra’s ownership is opaque. Aside from the shares owned by the Lebanese state and BDL, it is unclear how the rest are distributed. The Kuwaiti government, after Kuwaiti parliamentarians were scandalized to discover their government owned shares in a company affiliated with a casino, reportedly sold its shares in March 2006 to BLOM Bank on behalf of controversial Iraqi-British billionaire Nadhmi Auchi — who then reportedly sold to Lebanese-Palestinian businessman Abdallah Tamari. The National Bank of Kuwait is also a minority shareholder, while it is unclear if the Qatari government remains a shareholder. The remaining shares are owned by former investors and depositors in Intra Bank and their descendants, none of which have had a say in how the company is managed.

Even Intra’s ownership is opaque. Aside from the shares owned by the Lebanese state and BDL, it is unclear how the rest are distributed.

Figuring out how much profit Intra makes or how it distributes it is another jigsaw puzzle.

According to different sources in the press, 2003 was the first year Intra turned a profit since 1972. In May 2002, Asharq Al Awsat reported that Intra Investment Company was not generating any profits, and that it had a $40 million debt as well as cumulative losses of $28 million. Le Commerce du Levant reported that in 2003, Intra received $12 million in dividends from Casino du Liban and L.L. 9.5 billion in 2002 and L.L. 5.8 billion in 2003 from its subsidiary Finance Bank — its top two sources of revenue.

According to the Official Gazette, profits were L.L. 19.3 billion in 2008, L.L. 7.8 billion in 2007, and L.L. 9.2 billion in 2006.

The leaked audit of BDL, which mentions Intra very briefly, states that the company declared dividends in 2018, with L.L. 5.9 billion (around $3.8 million at the official exchange rate) going to BDL, while in 2017, no dividends were declared. The contents of this report, however, must be taken with a grain of salt; the auditors offer a “qualified opinion,” which is essentially an admission that they could not verify that the financial statements obtained are free from errors or omissions. “The report is basically telling you that [the auditors] are checking the accounts, but they don’t have the ability to actually do an audit,” veteran journalist and economist Mohamad Zbeeb explained.

According to an angry open letter published in the April 2005 issue of Al Mouacher magazine, Intra Investment had not distributed dividends in over 31 years to its individual shareholders — meaning those who had deposits in Intra Bank above L.L. 15,000 in 1966 and which were forcibly turned into shares in Intra Investment.

The company has not convened a general assembly to approve the company’s accounts since 2009.

Despite being a private company in which the state is the biggest shareholder, no data about Intra exists at the Ministry of Finance.

Tala Alaeddine, a researcher at Public Works Studio, recently collected data at the Finance Ministry for a project on state-owned lands. “Intra is not mentioned anywhere when it comes to the state’s properties,” she told The Public Source.

We asked Alain Bifani, director-general of the Ministry of Finance from 2000 until his resignation in July 2020, how Intra’s profits are distributed — given that the Lebanese state owns 10 percent of shares. “[Intra] is even hidden from us,” insists Bifani. “If there are a few small things we know about Intra, it’s because of Casino du Liban. Intra’s decisions in the casino’s board of directors was always the dominant decision because the company owns half of the shares. Apart from that, I have no idea what Intra owns. I think that practically it has become a real estate company, but more than this I don’t know. There is no clarity on what it owns.”

What Does Intra Own?

A confidential source provided The Public Source with Intra’s audit reports for the years 2019 and 2020, finalized by Deloitte Touche in November 2021 and January 2022 respectively. In 2018, Intra’s total assets were valued at L.L. 422.3 billion (or $278.7 million); in 2019 at L.L. 411.9 billion.

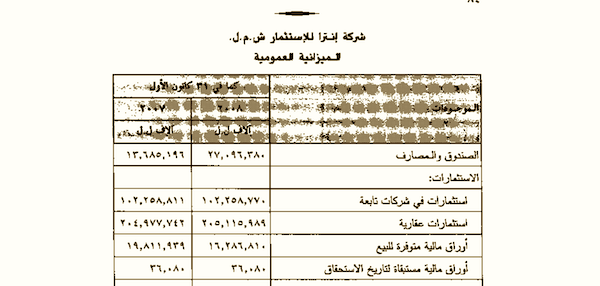

This valuation is a noticeable increase from the last figure published by Intra in the Official Gazette, in 2008, when assets were valued L.L. 366.8 billion ($242 million), with 56 percent classified as real estate. [note:1]

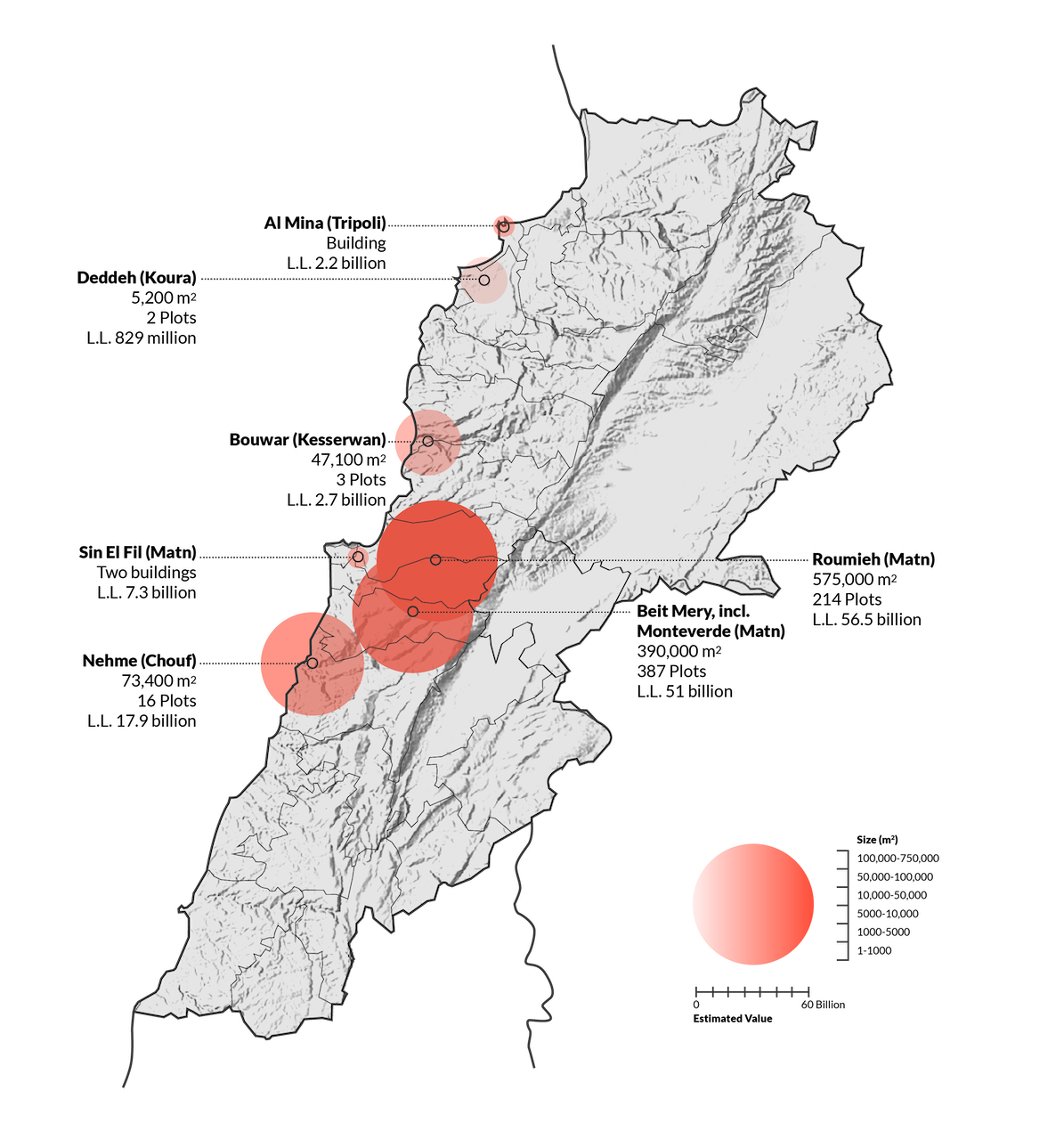

Based on the Deloitte Touch auditor’s report as well as documents from the government’s Land Registry, obtained in July 2021 via our partner Gherbal Initiative, The Public Source has compiled the following information of Intra’s most significant holdings.

Intra’s subsidiaries are primarily dormant companies whose value lies in the real estate assets they hold, which generate revenues through rent.

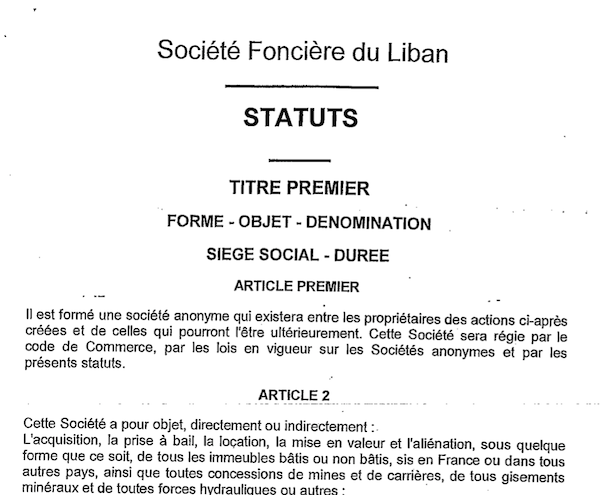

The Public Source retrieved documents on Intra’s subsidiaries that suggest they are primarily dormant companies whose value lies in the real estate assets they hold, which generate revenues through rent. Two of these subsidiaries are real estate companies based in France, chaired by Ghaleb Mahmassani, vice-president of the Beirut Stock Exchange, as per official documents obtained by The Public Source. [note:2]

Intra Investment Company's Real Estate in Lebanon

Source: General Directorate of Land Registry and Cadastre; Intra Investment Company auditor’s reports 2019 and 2020. (The Public Source)

Though we cannot confirm it, it is likely that all of the properties date to the days of Intra Bank, whose founder had substantially invested in the real estate sector. In all cases, the valuations are to be taken with a grain of salt, as they have not been updated since 1996.

Perhaps Intra’s most valuable real estate asset is the iconic Lazarieh building and its parking lot in Beirut’s central district — one of the few buildings in the area not owned by Solidere. Valued at L.L. 47.4 billion in 2019 (over $31 million at the official exchange rate), the building is one of Intra’s main revenue-generating vehicles.

Another Parastatal Institution for the Taking

For most of its existence Intra has been a honeypot for politically appointed chairmen and their benefactors.

When Intra Investment was established in 1970, it became customary for the president of the republic to appoint the company’s chairman. In a move of blatant nepotism characteristic of his presidency, Suleiman Frangieh appointed his son-in-law and former Foreign Affairs Minister Lucien Dahdah. Subsequent presidents would also install their man in Intra.

“This is how it is in Lebanon… If we look at the history of [Intra Investment Company], each president appointed the person who suited him as chairman of the board because Intra is an economic and political powerhouse,” Tamraz admitted, who himself was appointed as Intra’s chairman by President Amin Gemayel in 1983.

But this convention changed in August 1993 when Intra became one of the postwar spoils of Nabih Berri, speaker of parliament. Many paths through Intra’s labyrinth lead back to Berri.

For most of its existence Intra has been a honeypot for politically appointed chairmen and their benefactors. In 1993, Intra became one of the postwar spoils of Nabih Berri, speaker of parliament. Many paths through Intra’s labyrinth lead back to Berri.

First, Berri appointed Mahfouz Skaineh, who had served as first vice-governor of BDL (1990-93) and was known to be close to him. He also appointed his own brother, Mahmoud Berri, as Skaineh’s adviser.

By 1999, The Daily Star reported that Intra Investment Company was facing allegations of misappropriation of funds. In October 2001, Intra’s general assembly elected a new board of directors, with Mohamad Cheaib replacing Skaineh as chairman. A veteran banker, Cheaib is also reportedly close to Nabih Berri. Another member of the new board was banker Michel Ferneini, reportedly close to BDL governor Riad Salameh. Both Cheaib and Ferneini sit on the boards of the two France-based subsidiaries Intra owns.

Fenicia Bank — previously known as the Bank of Kuwait and the Arab World when it was still a wholly-owned Intra subsidiary — has been controlled since 1992 by the Achour family whose patriarch was a mayor affiliated with Berri’s Amal Movement.

Finance Bank, almost wholly owned by Intra, was chaired by Hassan Farran, also known to be close to Berri, from 1993 until a corruption scandal forced him out in 2018.

Both Finance Bank and Fenicia Bank were among the corporate sponsors of the 2016 annual gala of Randa Berri’s Lebanese Welfare Association for the Handicapped.

The Intra-owned Lazarieh complex, in addition to housing several companies, is also home to two non-governmental organizations affiliated with Nabih Berri: the headquarters of Medrar’s medical center, an NGO established by two of Berri’s children; and the administrative office of Phoenicia University, a private university in Zahrani that is owned by a foundation headed by Randa Berri. It is unclear if these organizations pay rent.

What is clear is that state institutions housed in the building do pay steep rents. According to an investigative report published in Al-Akhbar in 2005, the year the Ministry of Environment moved to the building, the state paid L.L. 232.5 million ($155,000) in annual rent, an amount that more than doubled by 2010, to L.L. 543 million ($362,000). The Ministry of Economy and Trade paid L.L. 472.5 million ($315,000) in 2010. A source in the Finance Ministry informed The Public Source that the annual rent is currently L.L. 800 million and L.L. 829 million, for each ministry respectively.

In short, since at least 2005, the Lebanese government has been paying rent in one of the most expensive areas in the country to a private company in which the government and BDL are themselves the biggest shareholders, but where no profits seem to funnel back to the state.

Apart from some taxes paid by Intra — property, value added, and income — as well as its employees’ contributions to the National Social Security Fund, the state seems to reap no benefits from Intra. Furthermore, the amount of tax paid has been progressively declining since 2018, from L.L. 3.7 billion that year to L.L. 2.9 billion and L.L. 2 billion in the two following years. In 2020, the company appears not to have paid any income tax, which was L.L. 835.7 million in 2019.

Intra operates as the perfect example of clientelistic postwar institutions. As sociologist Rima Majed told The Public Source, “while clientelism did exist before the civil war, it was pushed to new extremes in the post-war era. Even parastatal institutions were used to build a new kind of patronage for the post-war leaders to reinvent themselves, from militiamen to politicians.”

"Continuity, Stability, Investment," reads a faded, rusted sign in front of the iconic Lazarieh building in downtown Beirut, Intra's most valuable real estate asset. Beirut, Lebanon. May 8, 2022. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Snapshots of Intra’s Corruption

Intra is most visible through its control of 52 percent of Casino du Liban, which has long been scrutinized by the local press for corruption as well as power struggles between Lebanon’s oligarchs.

The postwar spoils-sharing unwritten norm has been that the president of the republic appoints the casino’s chairman — a situation that has created tensions with Berri’s control of Intra. In 2001, Berri, through Skaineh, reportedly imposed the hiring of several dozen partisans, to the consternation of politicians in Keserwan and Jbeil who long saw the casino nepotism as their exclusive preserve.

In the 2005 Al Mouacher open letter, the anonymous author accused Intra’s chairman and board of reneging on their responsibility to hold the casino’s chairman to account for not convening the board since August 2001 or a general assembly since March 1999.

In 2011, the casino once again grabbed headlines with corruption scandals during the presidency of Michel Suleiman.

Middle East Airlines was also subject to a political tug-of-war, this time between Berri and Rafik Hariri that culminated with Hariri’s former investment portfolio manager and BDL governor Riad Salameh injecting $225 million in Middle East Airlines in exchange for shares. BDL took quasi-totality of the airline, and since then, Intra Investment Company — which until 1997 owned 62.5 percent of the airline’s shares — has had no say in Middle East Airlines.

For its part, Fenicia Bank featured in the subsidized housing loan corruption scandal of 2019.

And then we come to the case of Finance Bank, one of Intra’s most secretive holdings. The bank’s website is no longer active and archived versions do not allow access to any annual reports or financial statements.

An article published in Le Commerce du Levant in June 2005 provides some clues. The bank was reportedly facing a low solvency ratio — it could not easily meet its long-term debt obligations — and was at risk of recording losses that year. Among the bank’s customers were influential Lebanese and Syrian politicians, while its administration was stacked with staff affiliated to the Amal Movement and close to then-president Emile Lahoud. The bank’s credits to the private sector were also politicized – one of its clients was a private company that carried out several projects for the state’s Council of the South, one of Nabih Berri’s spoils. Significant delays in paying back the loans were reported.

The Public Source spoke with a well-informed banking source who claims that the bank was used for political bribes ahead of parliamentary elections. “Whenever there are elections, suddenly thousands of accounts [in Finance Bank] would get created and money would get deposited in them, or the accounts would be credited,” he told us on the condition of anonymity. “Of course, the people never repaid these loans. It was a gift, a few thousand dollars each or so. The Banking Control Commission would approve the write off of these credit lines without sanctioning the bank’s management.”

“The Central Bank governor was also aware of the gross violations and corruption in Finance Bank,” he adds as an afterthought.

Leaked minutes from a meeting of the Finance Bank board dated October 2, 2015, give credence to such accusations. They indicate that the board gave preferential treatment to the Amal Movement and then-army commander Jean Kahwaji, his wife and three children.

This prompted an illicit enrichment lawsuit against Kahwaji, which opened a judicial investigation that snowballed to include seven other senior military figures. But given the desultory state of the judiciary in Lebanon and the banking secrecy law, it is no surprise that the lawsuit is “dead.”

In 2017, an article in an Iraqi publication claimed that Hassan Farran, the bank’s chairman since Intra came under Nabih Berri’s grip, had reportedly bribed the governor of Basra to obtain lucrative contracts for a Dubai-based energy company which he co-owned.

In 2018, BDL’s Higher Banking Commission, the highest banking judicial authority in the country, reviewed a report from the BCC on Finance Bank’s activities and listened to the testimony of Farran. But rather than liquidate the bank and terminate its activities, the commission decided to simply dismiss Farran and replace the board. Farran appears to have fled to London, his whereabouts unknown.

“[Finance Bank’s] chairman bankrupted the bank and nobody held him to account, because one of the people who protected him is one of the prominent politicians,” a senior banker with knowledge of Intra’s activities told The Public Source on the condition of anonymity.

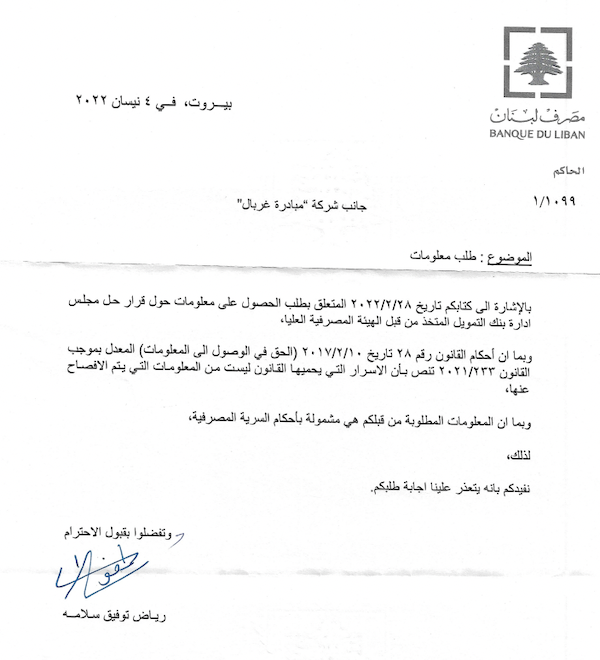

The Public Source submitted information requests to BDL via Gherbal Initiative to obtain the BCC report in February 2022. But on April 4, a letter from Riad Salameh informed us that the information requested fell under banking secrecy, and hence could not be disclosed. [note:3]

But perhaps Finance Bank’s most egregious element is in the details of how it made any profit at all.

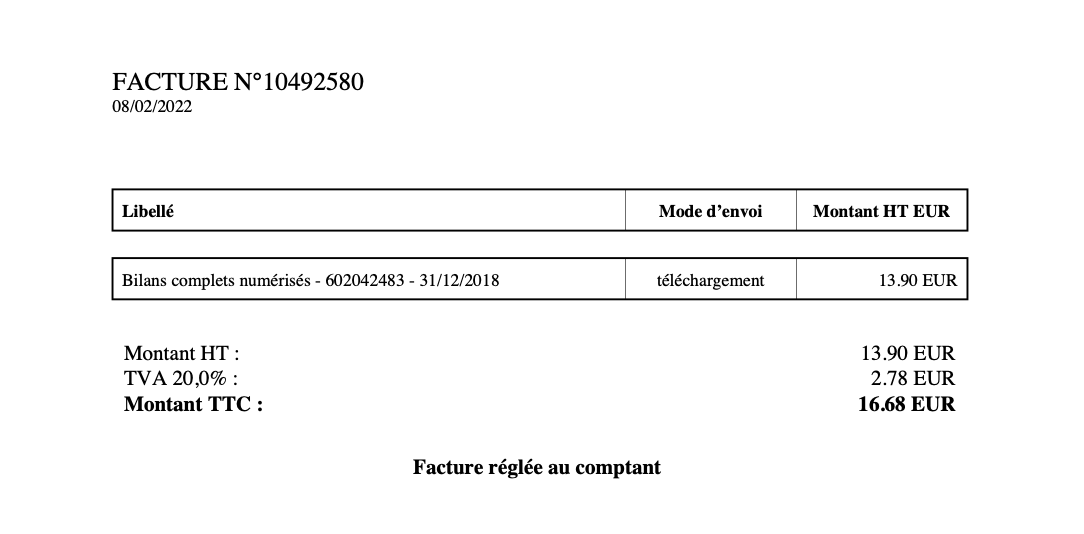

According to Le Commerce du Levant, the bank’s main source of income was its long-term Eurobond purchases, i.e., its foreign-currency denominated debt, which it started selling to customer in 1997. [note:4]

In May 2002, hundreds of posters by Finance Bank were plastered all over Beirut, inviting customers to invest in Eurobonds. The bank’s director of the Treasury Bonds department explained that customers could purchase Eurobonds through Finance Bank.

This was in line with the practice of Lebanese private banks that led to the financial collapse. But here was a bank owned partially by the state making its profits by lending to the state, at the expense of public debt.

According to Nabil Abdo, senior policy advisor at Oxfam, “between 1994 and 2010 [...] tax revenues constituted 97 percent of debt service. Practically this means that the totality of taxpayers’ money went to repay debt, which means that most of this money went to the banks.”

Intra as a Warning

The case of Intra should serve as the perfect deterrent to the calls to privatize state assets.

The realization of how much real estate is up for grabs quantifies what the public would be losing irretrievably — a point Public Works Studio has emphasized in their campaign against a firesale of state-owned lands.

“Any attempt to bail out the banks via confiscation of public assets ... would further erode any remaining semblance of public space and potential sources of revenue for safeguarding national economic sovereignty by future governments.” —Hicham Safieddine, scholar

“Any attempt to bail out the banks via confiscation of public assets is dangerous” as this would be “another unjust transfer of wealth from the entire Lebanese people, including future generations, to those responsible for the crisis,” argues Hicham Safieddine, scholar of Lebanon’s political economy, in an interview with The Public Source, adding that it would also have “a long term effect of further eroding any remaining semblance of public space and potential sources of revenue that may be used for economic development and safeguarding of national economic sovereignty by future governments.”

Yet Intra’s sordid history also paints a crystal clear picture of what a joint-stock company looks like in Lebanon: a deliberately opaque, criminal network of blurred lines between politicians and businessmen, where oligarchs only fall when the rest covet their spoils. Criminality at an even grander scale awaits us if similar structures are set up while nothing else changes.