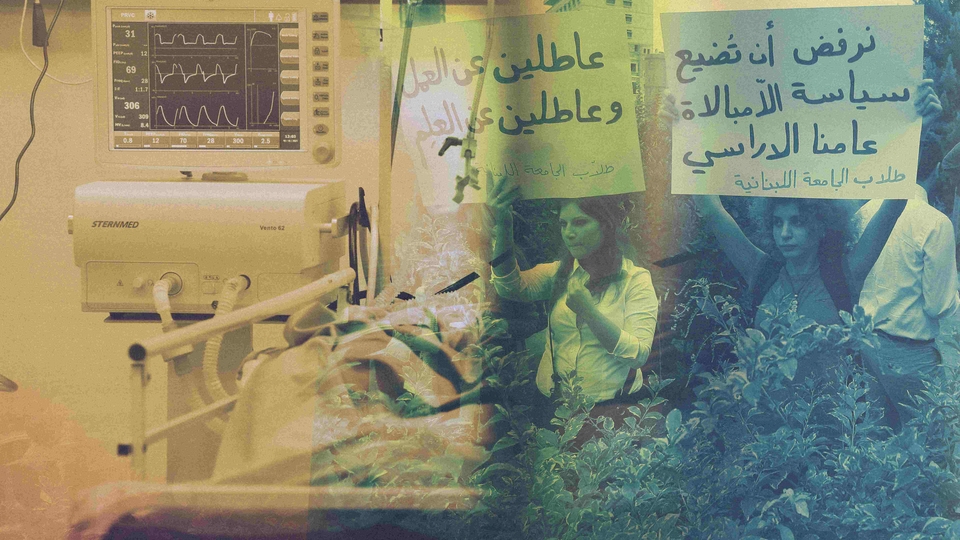

Students or Workers? Lebanese University Medical Students on the Frontline of a Crumbling Healthcare System

Editor's Note: The names of the individuals interviewed for this story were changed to protect their identity due to the Lebanese University's history of retaliation against students who speak out against the administration.

Majd had only been training at the hospital for a few months in 2018 when he was tasked with accompanying a patient in an ambulance for a hospital transfer.

There was one problem, however, the sixth year medical student had not been taught how to handle this kind of situation.

“They gave me a first aid kit and I didn't even know how to use it,” the 25-year-old tells The Public Source. “If anything had happened to the patient during the ambulance transfer, I couldn't have done anything, I wouldn't have known what to do.”

Majd’s experience is far from an anomaly. Lebanese University (LU) medical students who spoke with The Public Source all found themselves in similar situations, having to make decisions they were not qualified for, without supervision or support from their university or the hospitals where they were supposed to be learning the ropes.

Lebanese University medical students found themselves having to make decisions they were not qualified for, without supervision or support from their university or the hospitals where they were supposed to be learning the ropes.

Starting as an intern in 2018, Nour was immediately thrown into work they had not yet acquired the skills for.

“I arrived on my first day at the hospital super confused, and I directly started with clerical work such as writing a patient report, preparing a medical file, talking to the insurance company...” Without any guidance, Nour had to learn all this by themselves.

Majd and Nour are among a large number of underpaid and unprotected students who have been bearing the brunt of the multiple crises in Lebanon’s healthcare system since 2019.

Students have been on the frontline of the COVID-19 pandemic; navigated shortages in equipment due to the currency devaluation; survived on meager wages amid soaring inflation; and responded to the catastrophic Beirut explosion on August 4, 2020. Now, they also have to face these crises practically alone, as doctors and other medical professionals leave the country in droves.

A health worker prepares an operation room at the Beirut Governmental University Hospital. Beirut, Lebanon. October 19, 2021. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Thrown in at the Deep End

On paper, LU students complete five to six years of in-class medical education before they start their internship at partner hospitals, while continuing to attend classes and conferences. During their internships, medical students are supposed to be accompanied by residents at all times and have little agency in a patient’s treatment. Physicians supervise and guide the interns, intervening when necessary.

After two years as interns, medical students earn their MDs (Medical Doctor) license, become residents, and subsequently start specializing in their chosen field of medicine. Residents have a little more leeway and responsibility, but they are still supposed to report to more experienced physicians and receive consistent guidance.

In practice, however, medical students enrolled at the only public university in the country face a different reality, both as interns and residents.

Even though all students should be treated equally, Nour was shocked while on rotation at a university hospital by the differential treatment of public versus private university students.

Even though all students should be treated equally, Nour was shocked while on rotation at a university hospital by the differential treatment of public versus private university students.

“These students had doctors following up with them and teaching, explaining everything to them. They would go see patients together, go over the medical files, and have meetings in the cafeteria,” Nour recalls.

Meanwhile, Nour and their LU peers were left behind. Supervising physicians would act annoyed when contacted by LU students looking for guidance. Majd tells The Public Source a physician once yelled at him when he called to inquire about the care of one of the doctor’s own patients.

Chantal Akkari studied medicine at the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik (USEK) and currently works at the American University Hospital (AUH) as a resident in radiology. She tells The Public Source that AUH administration treats medical residents equally, regardless of where they completed their MD, but that she has noticed a difference in how private and public universities train and treat their students.

“[LU] students do not get the same supervision and support we get. At the Lebanese University, when students are in their last year, they have duties they complete on their own, and they don’t have doctors by their side,” the third-year resident says.

“In AUH, this is completely forbidden. If we’re med students, we’re not allowed to place any medication order or anything else without a resident or a fellow [who has] to co-sign everything,” she adds. “This is very important and it impacts the patients’ safety.”

A monitor displays the vital signs of a patient at the Beirut Governmental University Hospital. Beirut, Lebanon. October 19, 2021. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Long Hours, Low Pay

All medical students are expected to work 80 hours per week on average. During a day shift, residents are expected to work from 8 a.m. to 3 or 4 p.m. They go door-to-door during morning rounds, examine hospitalized patients, check lab and X-ray results, then brief the physicians on their patients. They then move to clerical work related to insurance reports and medical files.

Residents are also expected to cover the night shift once every three days, during which they are usually assigned the emergency room (ER). Once the night shift is over, they have to stay for the morning rounds and cannot leave before noon. This results in 28-hour shifts twice a week.

For some, weeks and nights drag even longer. Majd has been taking up additional night duties as an ER resident at different hospitals to make ends meet.

When he started working at the hospital as an intern in 2018, first-year LU interns were paid L.L. 600,000 per month, less than the minimum wage at the time of L.L. 675,000 — the equivalent of $450 then, but barely worth $28 on the parallel market at the time of writing. Second-year interns were paid L.L. 700,000 monthly; first-year residents L.L. 1.2 million, and second-year residents L.L. 1.35 million. While these wages allowed LU medical students to get by at the time, they quickly became worthless as the country plunged into an economic crisis.

In May 2020, many of LU’s contracted hospitals started annulling contracts, jeopardizing the future of the students. To cut down on expenses amid the financial downturn, only half of LU’s medical trainees would be granted residencies.

In order to keep offering spots to all students seeking internships and residencies, Nour and Majd say that the LU administration reached an agreement with hospitals a few months later, whereby first-year interns would not be paid. In exchange, residents were promised that their wages would be adjusted to the new exchange rate — at the time, the bank rate was L.L. 3,900 to the dollar, while their salary was still based on the old rate of L.L. 1,500 to the dollar. A year later, the hospitals and university have yet to keep their promise.

Medical students, frustrated by their back and forth with both hospitals and the university, whose administrations threw the responsibility on one another, started exploring the possibility of going on strike. But once the administration learned of their plans, it threatened them with internship invalidation, meaning they would have to repeat a year, and even suspension.

Once the administration learned of students' plans for a strike, it threatened them with internship invalidation, meaning they would have to repeat a year, and even suspension.

“We faced a lot of opposition and threats, so we had to go back to our jobs and they agreed to adjust our salary but said they couldn’t give us more than double. Of course we kept demanding more because this amount is still not enough, especially that [fuel] subsidies were being lifted and the salary barely covered our transportations expenses. But they were really threatening us so we had to accept,” Majd explains.

Moreover, many students felt uneasy with the idea of walking out of hospitals where patients’ lives depended on them due to chronic understaffing. Without the medical students, "there would be no one," Majd says.

“Students Are the Solution”

The strike never took place, but the threat of one pushed hospitals to double the residents’ salary, a long overdue adjustment that was insufficient given the continued downward spiral of the Lebanese currency, but one that students had to accept. The raise was approved in August 2021, partially put into effect in October 2021, then fully implemented in November 2021.

University hospitals, aware that the adjustment was not suitable, promised additional raises once fuel subsidies were lifted in order to compensate for the skyrocketing cost of transportation.

Yet four months later, salaries for LU medical students have not changed. Meanwhile, private universities have taken action to increase their residents’ salaries. In February 2022, the American University of Beirut announced a new financial plan for first-year residents that would allow them to be paid partially in dollars, making their monthly pay around L.L. 22 million, while LU residents are getting paid L.L. 2.4 million.

LU Faculty of Medicine staff contacted by The Public Source dismissed queries about the medical students’ low wages by comparing them to their own meager salaries at the underfunded public university.

LU students are far from the only ones struggling within Lebanon’s healthcare system. The Lebanese Observatory for the Rights of Workers and Employees, a group of activists, workers, employees, professors, lawyers, and unionists, has noted an increase in protest movements at the level of governmental hospitals over the past year.

“The demands are varied. They range from paying dues and problems with low wages to demands to secure immediate contributions from the Ministry of Health to support them,” Assaad Sammour, the head of the observatory’s media unit, tells The Public Source.

Even though LU medical students didn’t fully achieve their goal of obtaining a living wage, Sammour believes that, by making their voices heard, their movement was an important step forward.

“Students are the solution,” Sammour says. “The most important element in the protection of their rights is the student movement that should defend their interests.”

Lebanese University students have been fighting for their rights for decades. In 2011, they gathered in front of the parliament to stand with their professors’ strike. Beirut, Lebanon. October 25, 2011. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Doctor Exodus

The burden on students has been made even heavier by the mass departure of medical professionals from Lebanon in recent years. As of September 2021, “almost 40 percent of skilled medical doctors and almost 30 percent of registered nurses have left the country either permanently or temporarily,” according to the World Health Organization.

Majd laments the loss of the few good doctors who had contributed to their education. “My training wasn't good from the start, but there were good doctors who were passionate about teaching students,” he says. “Now they all left in the mass exodus, so of course my training and education were affected.”

Other LU medical students are more cynical, saying they have not felt the impact of this exodus, as they had little guidance and support from physicians in the first place. “Nothing changed for me, other than the number I call when things get really bad at the hospital,” Nour says.

“We’ve always been alone.”

Professor Eliane Ayoub, the adjunct medical director of academic affairs in charge of interns and residents from Saint Joseph University at Hôtel Dieu hospital tells The Public Source that while it has not been the experience of some private hospitals, the exodus of doctors is bound to affect medical training, and thus patient care.

“If there are no physicians, patient care will be worse, that's evident. And if there are no physicians, students' training will be worse, this is also evident," she says.

Students, Student Workers, or Workers?

Amid these hardships, one question remains at the forefront of LU medical students’ minds: What, exactly, are they?

Without the necessary training and supervision, and without adequate protections and pay, LU interns and residents fall through the cracks of a system in which they don’t have a clear standing.

“If it’s easier [for us] to be kicked around as employees, we’re employees. And if it’s easier as students, we become students. I’m neither. I have no standing anywhere,” Nour tells The Public Source.

“If it’s easier [for us] to be kicked around as employees, we’re employees. And if it’s easier as students, we become students. I’m neither. I have no standing anywhere." Nour —Lebanese University student

As part of its agreement with hospitals, LU awards student contracts, but these do not prioritize the students’ learning needs, according to Nour. The details of these arrangements are not disclosed to students, who are kept in the dark about their own labor and future. For instance, the contracts do not mention salaries, thus leaving students unable to negotiate an official rate with the university or hospital, who both use “training” as an excuse to pay poorly, Nour says.

A staff member at the Faculty of Medicine, speaking on the condition of anonymity because they had not received permission to speak to the media from the dean’s office, confirmed that students do not have access to the contracts signed by the university and the hospitals.

According to Article 19 of the Lebanese Code of Labor, employers must pay trainees starting on the third month of their internship. Sammour, the labor activist, says that this article is supposed to be implemented for medical interns and residents.

“I think hospitals don’t grant students their rights as workers because of the agreements made with LU. In addition, compliance with the law needs power to prevent business owners, including hospitals, from violating their workers’ rights,” Sammour says — a power the Lebanese government lacks because unions, judicial courts, and the inspection department at the Ministry of Labor are weak, he adds.

The pandemic has further exemplified how this limbo leaves LU medical students vulnerable. When students who were concerned about contaminating their families refused to work on COVID-19 floors, they were threatened with invalid internships once again.

“They’re putting you at risk by force, you don’t have the right to say no,” Nour tells The Public Source.

University and hospital officials were not forthcoming when contacted for comment by The Public Source on the working conditions of LU medical students. The dean, the general secretary, the head of the medicine department, and both the former and current coordinators of clinical internships at the Lebanese University school of medicine did not respond to repeated interview requests via email and phone calls. They were not present in their offices upon visit; a janitor explained that administrators and staff only work on campus a couple of hours two days a week. The medical director of a private hospital denied the students’ claims then retracted his answers under the pretext of wanting to clarify his statements during an in-person interview, then stopped responding to further calls.

Two staff members work at their desks at the Beirut Governmental University Hospital. Beirut, Lebanon. October 19, 2021. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Unrepresented and Unprotected

The only structure that is officially tasked with protecting the students’ rights is LU’s student council. But according to the residents who spoke with The Public Source, the same organization tasked with advocating for them is stalling and diffusing the momentum of student mobilization, in order to keep the peace for the administration.

The university’s student representatives are not democratically elected, and the council’s composition is built on sectarian representation: Each class gets two representatives, each from a different sect and affiliated with a political party.

“Personally I don't think [student representatives] ever worked in our favor,” Majd tells The Public Source.

A former student representative who spoke to The Public Source says her role was limited to relaying messages from students to the administration, managing logistical issues such as setting exam schedules, printing and distributing lessons, and coordinating work groups, as well as organizing social events.

“We used to take care of more general issues. For example if students feel like having a gala dinner, or a charity event, of course we would help them, ” she says. “I remember we used to put up a Christmas tree and a nativity scene with Jesus. For Ashura, guys would dress in black. We used to remember and respect each other’s rituals,” she boasts.

Perla Nader who took on the role from 2013 to 2019, tells The Public Source that she was chosen by the older promotion of medical students to represent the students of her class over the course of the program.

“The ritual at the LU has always been about having two people as class representatives, one Christian woman and one Muslim man for equal representation,” Nader tells the Public Source.

“Usually, elections are supposed to be held, but I was told that in LU, especially on Hadath [campus], elections are very sensitive and could create issues,” she says.

The lack of real agency of student representatives is further compounded by the fact that they are not able to keep track of the struggles faced by students once they are scattered across different hospitals for their internships.

“We don’t know what the policy or the job description of the hospital says,” she tells The Public Source. “We, as students, don’t know what’s in those contracts.”

“We don’t know what the policy or the job description of the hospital says ... We, as students, don’t know what’s in those contracts.” —Perla Nader, former student representative

At the same time, medical students cannot join the Lebanese Order of Physicians before acquiring their MDs, i.e. at the end of their seventh year — which deprives them of another channel to demand their rights. Even as residents, most stay out of the syndicate because of lengthy paperwork and unaffordable fees.

“I think there should be a role for the Order of Physicians because it’s unacceptable to treat medical students who will soon become doctors this way,” Sammour argues.

He points out that syndicate work is not only built on knowledge of labor rights, but most importantly on solidarity.

“Solidarity is the pillar on which syndicate work is built,” he says. “This awareness is still crystallizing and has not yet reached the point where it can stand firm against the sectarianism that has planted firm roots in the Lebanese identity because of the political and economic system in place.”

However, Sammour adds, “student movements are more effective than syndicates in fighting for the rights of students because students themselves know their interests better and can express their demands.”

Disillusioned by the System

Lack of training and guidance, in parallel with the absence of protection from both the student body and the professional syndicate, has left many LU medical students feeling unprepared to officially join the medical workforce.

Majd and Nour have finished their two-year hospital internships and earned their MDs. Now residents, they still feel unable to handle all the responsibilities thrust upon them — but they make do because patients’ care depends almost solely on them.

“They want us to make life-or-death decisions [on our own] just to avoid calling and waking up a doctor at night,” Majd tells The Public Source.

Both are considering different tracks in the paramedical sector, away from medical practice.

Majd decided to finish his residency to obtain a diploma before joining a different non-medical program. He says he had expected more follow-up and rigorous training, “We are sent to university hospitals, which are teaching hospitals, and we’re not even getting the education we’re meant to get.”

“Honestly, I don’t like practicing medicine anymore,” he says. “I'm barely getting paid, barely able to go to work because of fuel prices, there is no motivation to go to work. It’s like being enslaved.”

Nour wanted to be a doctor to help people in need. Now, they say they are aware that when it comes to the real world, things don’t go as expected, “We see injustice and unfairness and we can't do anything about it.”

When asked how their experience is different from what they had expected when they started, Nour scoffs, “How could I have known. I wouldn't have believed it if someone had told me this is how it is.”

Nour did their own research to palliate the lack of guidance and support, but it could not replace proper training.

“I feel like I do know how to work and I’m good at my job, but deep inside, I feel like a charlatan,” he says.

Now, their dream is to find a way to change the healthcare system at its root.

“Working long hours, being super stressed, making dangerous life-and-death decisions, it’s not something to be romanticized,” the MD says. “It’s needless stress, it’s dangerous to yourself and to others, and it’s perpetuating a chain of abuse.”

“I don’t want to romanticize labor as a criteria to evaluate a person. Working long hours, being super stressed, making dangerous life-and-death decisions, it’s not something to be romanticized,” the MD says. “It’s needless stress, it’s dangerous to yourself and to others, and it’s perpetuating a chain of abuse.”

“The respect you’re supposed to get as a doctor doesn’t make it better or change the fact that I’m not adequately compensated or treated respectfully at my job.”