“Like a Prison”: Lebanon’s General Security Makes Passport Renewal a Nightmare

In March, Salim and his wife Aida (who requested that their names be changed for privacy) showed up on time at the General Directorate of General Security (GDGS) headquarters in Beirut to renew their passports. But only one of them left the building with a passport in hand.

The employee processing Salim’s paperwork told him he did not fall under any priority category for travel, such as residency, work, medical treatment, or education. Aida, however, was eligible for a new passport since she had a valid Canadian tourist visa.

“Why are they restricting my freedom?!” Salim exclaims, recalling the employee’s refusal to process his application.

Getting a passport in Lebanon was once a smooth and fast process. But over the past two years, requirements to renew one’s Lebanese passport have changed, often unannounced.

In late April, General Security announced in a circular that it will stop booking appointments for passport renewal because of a shortage of blank passports. This came after GDGS established an online platform to facilitate passport renewal appointments on January 27, 2022, where people had to wait months for a reservation.

Ghida Frangieh, lawyer at research and advocacy organization Legal Agenda, says the circular isn’t just unfair, but is also illegal because it violates the constitutional principle of freedom of movement. This sudden change comes "at a time of great political and socioeconomic instability" and infringes on the right to mental well-being, according to Frangieh.

“Why are they restricting my freedom?!” —Salim, whose renewal application was rejected.

General Security’s shortcomings is an example of the mismanagement at the heart of the state. Living conditions in the country continue to decline, and now leaving Lebanon has become an even more difficult feat.

“They’re basically turning Lebanon into a prison,” says Celine, whose father Salim was unable to renew his passport.

No Escape From Economic Crisis

After the inevitable collapse of decades of neoliberal political economy, Lebanon's authorities and banking sector have failed to stabilize the country's spiraling currency, control soaring inflation, and provide viable social protections. The Lebanese pound has lost 90 percent of its value against the dollar, while 82 percent of the population live in poverty.

The economic crisis and the pandemic have also affected public sector employees. Unable to provide employees a salary correction to match the inflation and ever-increasing fuel prices, several public administrations decided to decrease the number of hours employees clock in to work. For this reason, most public sector employees only come to their workplace a few days a week, which causes processing delays.

While worker strikes in the public sector have slowed operations in several public institutions, processing delays at GDGS are the result of a top-down decision to reduce staff hours. Because GDGS is a security apparatus, its employees cannot unionize or strike, according to Frangieh.

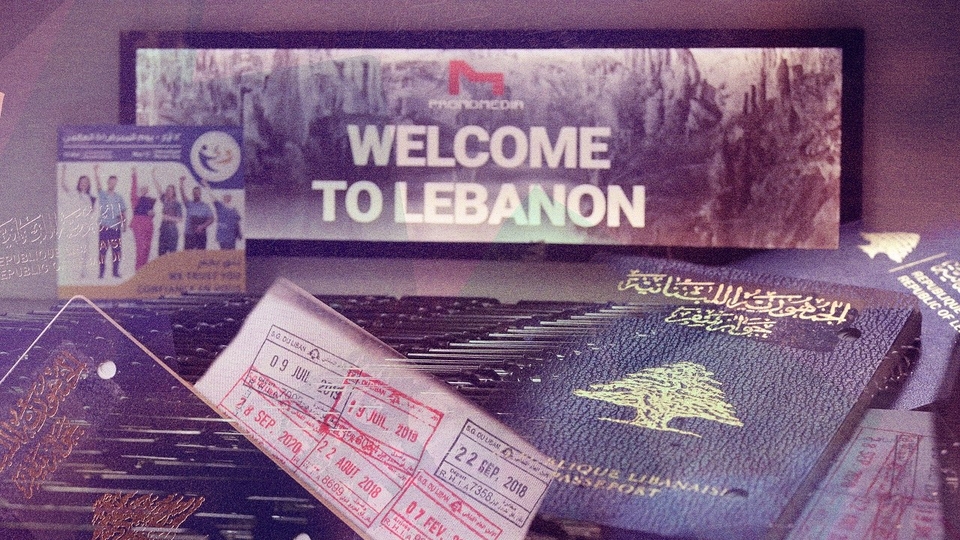

"Welcome to Lebanon”, you can check-in any time you like but you can never leave. August 1, 2020. Beirut, Lebanon. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Meanwhile, more people in the country are considering emigration. According to a Gallup poll, 63 percent of Lebanese would like to permanently leave the country. Over the past year, 77,000 Lebanese have left the country. In parallel, General Security reported that 260,000 people renewed their passports between January and August 2021, almost double the renewals in the same period in 2020.

“Citizens need to be able to plan for their future, and these types of sudden and indefinite measures don’t allow you to plan,” says Frangieh. “A war might break out tomorrow. We need to be able to leave.”

According to a Gallup poll, 63 percent of Lebanese would like to permanently leave the country.

Not only does placing a hold on passport renewals infringe on freedom of movement, but it also transgresses the right to identity documents.

“[A valid passport is also] a recognition of our legal identity towards non-Lebanese authorities and entities,” she continues, and is necessary for educational or professional activities governed by foreign entities within Lebanon.

The GDGS did not take non-travel related needs into consideration when it imposed travel documents like flight and hotel bookings to be presented for the renewal application to be processed. Paradoxically, the bookings also require a valid passport in the first place, so passport applicants end up stuck in a loop to get their paperwork in order.

“They're not giving passports unless you ‘need’ them to travel. But we also need our passports for reasons other than travel.” Frangieh says.

Another Case of Poor Planning and Denial

In an interview with Qatari newspaper Al-Sharq in December 2021, General Director of GDGS Abbas Ibrahim blamed the inability to produce passports on high demand. Rising demand, he suggested, is not because people want to desperately leave the country in crisis, but because they're worried that the GDGS was running out of blank passports. He claimed that fears are what “doubled the demand,” despite admitting in a previous interview that GDGS had accumulated a deficit of 5,000 passports per day.

An investigation by Daraj from last month reveals that the shortage of blank passports falls on a private company and the Central Bank. Inkript, the digital security company contracted to produce blank passports — owned by Future-affiliate Hisham Itani — had not delivered the requested quantity because Lebanon’s CB has not paid the company, as stipulated in the contract. As a result, General Security chose to use the limited supply exclusively for citizens who had already booked their appointments. GDGS then announced they would no longer be accepting appointments until further notice due to the shortage.

In its latest statement, the GDGS said it will be advancing the appointments of people receiving medical treatment abroad. It is unclear whether the company and the CB have reached a resolution to reinstate the delivery of blank passports.

Lawyer Ghida Frangieh says GDGS’ denial and poor planning — particularly, the failure to anticipate what appeared to be an inevitable shortage — are also to blame for the passport freeze. Rather than take precautionary measures, General Security spent over a year publicly denying the issue.

In summer, fall, and winter of 2021, GDGS officials repeatedly declined that supply was an issue, insisting that it was a rumor.

“There is no problem with passports,” Ibrahim insisted.

Frangieh says GDGS’s denial and poor planning — particularly, the failure to anticipate what appeared to be an inevitable shortage — are also to blame for the passport freeze. Rather than take precautionary measures, General Security spent over a year publicly denying the issue.

Dreadful Process in Line, Online, and Abroad

Lebanon is experiencing its third wave of mass emigration in its history due to the economic crisis. Throughout 2021, long queues in front of many of the 54 General Security offices across the country would often last well into the night.

One October eve, at 8:00 p.m., Lynn Hodeib joined a queue at the General Security headquarters in Adlieh. At 4:00 am — after eight exhausting hours of screaming, cutting lines, and arguments with guards — officers wrote down the names of the people who would get an appointment, and dismissed the rest. Lynn was the last one to make the cut.

“Some people came from Akkar with their toddlers for this, many times, and were sent back. It felt horrible,” Lynn recalls. “I heard a woman scream because they didn’t give her a number; another man just sat on the ground and stared at the wall … I remember writing about it and crying on the way back.”

But things did not end there. She was told to come back an hour later to receive her appointment number. Drained of all energy but unwilling to lose her spot, Lynn decided to take a 30-minute nap in her car and made it back just as they were calling out her name. She was asked to leave again and come back at 10:00 a.m. for the actual appointment.

Hassan (who requested for his last name not to be used) — with plans to leave the country as soon as he can — was less fortunate. He was able to obtain an appointment from the Choueifat branch on his fourth attempt. He says the first three times he was turned away, either because the officer in charge was not in or because the center was out of blank passports.

When Hassan finally got to his appointment, the system at the center was down. “We sat for four hours waiting for the system to work… It didn’t,” he says. Other people who spoke with The Public Source experienced other logistical issues at the Choueifat branch. They were told the fluctuating electricity supply had damaged the biometric photo machines.

Hassan went back three days in a row, in vain, and was giving up, until they called him back a week later. Even then, bad connectivity caused the process to take longer than it should have.

“They’re just very inefficient and slow…” the 23-year old digital strategist says.

A traveler shows a travel document to a customs officer at the airport. August 1, 2020. Beirut, Lebanon. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Elie Abi Khalil, a 24-year old cancer biology student who requested the “expedited” process, noted the irony of having to wait for hours and being led on a wild goose chase to retrieve his passport.

In the first three months of 2022, the online process was meant to alleviate some of the frustrations and humiliations in GDGS queues. However, the online waiting list quickly became so long that on April 19, the earliest open slot in Beirut was in October 2022 for regular renewals and — paradoxically — January 2023 for expedited requests.

Nada (who requested for her last name not to be used) was relatively lucky. When she logged onto the General Security platform on March 19, she found a slot less than a month later, on April 13.

During a visit to the local municipal authority (mokhtar), he informed her that new requirements had been introduced: applicants needed to show proof of residency, education, or medical treatment abroad; have proof of a visa appointment at a foreign embassy or consulate; or a plane ticket.

In anticipation, Nada had a travel agent book her a fake plane ticket and hotel reservation in Turkey which does not require visas from Lebanese citizens. Once at the General Security office in Adlieh, she was indeed asked to show the bookings in order to be let in.

“It was very easy because my papers were ready,” she says. Had she not been warned, however, she would have lost her appointment.

According to Frangieh, by not providing notice of the new requirements to the public, General Security failed to meet the basic rules of the legal relationship between a government body and its citizens: the principles of legal security and legitimate trust.

“These principles necessitate that the government body takes transitional measures to allow people to organize and prepare themselves for a change of rules,” Frangieh explains. Instead, “General Security released circulars that are implemented directly, without granting the public notice or time to prepare,” violating citizens’ trust in legal rules and their continuity.

“Some people came from Akkar with their toddlers for this, multiple times, and were sent back. It felt horrible,” — Lynn Hodeib, who waited in queues in October.

Frangieh also explained that General Security has no legal jurisdiction to modify conditions on obtaining a passport. According to Lebanese law, the cabinet decides which documents are required to receive a passport.

Even as some Lebanese have managed to leave the country, the passport renewal process abroad is still tiresome.

Ali (who requested for his last name not to be used), a PhD candidate in Germany, needed to renew his passport for his residency permit. In November 2021, he drove three hours to the Lebanese embassy in Berlin.

His options were a one-year passport, which would be a hassle to renew for his residency every year, or a ten-year passport, which would cost him €530—around $560.

“I was so pissed. I didn’t know I was signing up for this. I had to pay three to four months’ worth of savings to get a shitty passport,” the 27-year-old said, frustrated.

Ali says he felt pressured, as one of the employees at the embassy wagged the credit card machine in his face and said “Yallah, get the ten-year passport.”

“I felt it was a scam; a way for the government to rip off the people who are living abroad [...] but I have to accept it because I’m Lebanese.”

To avoid the exorbitant costs abroad, Michelle Ellis wanted to renew her passport, which was five months from expiry, while visiting Lebanon from the UK in February. The earliest slot she could find was after her booked return.

“I thought I would have to cancel my flight,” the 27-year-old recalls. “I called a thousand times and no one answered. When they did, they kept transferring me from one person to another and hanging up on me.”

Desperate, Ellis reached out to a personal connection (wasta) and was able to renew her passport on time. It was only when she went that she was informed the fees had increased since she had last looked up the requirements.

“Some people didn’t know this and didn’t have enough money on them to pay. They had to leave and make a new appointment to come back because the price increase had not yet been announced. They just tell you when you get there,” she tells The Public Source.

General Security has no legal jurisdiction to modify conditions on obtaining a passport.

She paid L.L. 1,200,000 for a 10-year passport, and an additional L.L. 1,050,000 for the expedited process — L.L. 2,250,000 in total (around $70).

Michelle was only able to obtain the passport because she had the financial means and the connections to facilitate the process. For most, this is not the case.

Governmental negligence meeting decades of economic policies of dispossession have pushed people to their last resorts — be it clientelistic relations or desperately boarding life-threatening boats — as there is no standard mode of operation.

By denying many citizens the ability to apply for a passport, the GDGS is in violation of the constitutional principle of equality between citizens, Frangieh notes.

A Dangerous Last-gasp Effort by Sea

On April 23, 2022, only a week prior to the platform shutdown announcement, a boat carrying more than 80 people trying to flee the country and its harsh living conditions drowned after an army vessel rammed into it off the coast of Tripoli.

“Some victims said that they took the boat because they couldn’t get a passport,” Frangieh says. Survivors confirmed to The Public Source that they had unsuccessfully tried to renew their passports for legal travel.

“One of the things that has driven us to the point of leaving illegally is that there are no passports,” Maher Hmouda, one of the survivors, tells The Public Source. “We have money. If we could have gotten a passport we would have traveled legally to any country but they are not giving us passports.”

Hmouda had tried time and time again to book an appointment through the platform, only to find no available slots. Frustrated, he went to the General Security and was turned away in person. Eventually, he made the difficult decision to be part of this migration attempt aboard the death boat.

Lebanon’s General Security offices are no longer renewing Lebanese passports. April 8, 2022. Beirut, Lebanon. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Clientelism Rules the Process

Countless Lebanese, like Michelle, have resorted to wasta to get their passports in a timely manner. But for some, even high-ranked connections could not help. Salim’s attempts to seek the assistance of his influential acquaintances led nowhere, despite having his paperwork in order and an appointment at the General Security.

For everyday people, wasta is often used as a last-ditch effort to access services, after honest attempts to go through the correct channels.

These channels are governed by the same clientelistic networks.

Inkript, the company contracted to produce biometric passports in 2015, is owned by Hisham Itani — Future-affiliate and son of ex-parliamentarian Mohammad al-Amin Itani — and is not without its financial and legitimacy scandals. The passport tender was reportedly worth $35 million at the time.

Additionally, the GDGS online platform that emerged to facilitate appointments was funded and developed by Hani Saliba, a parliamentary candidate who ran and lost in the May 15 parliamentary elections.

Frangieh articulates how the passport saga played out in this year’s elections. “The passport has become an electoral favor; in order to obtain a passport, we have to talk to politicians who will use this favor to try and get our vote,” she says. “Clientelism.”

The inability of public sector offices such as General Security to provide people with basic services stems not only from an administrative failure but also from the political class that is not providing these offices with the means to do so, Frangieh continues.

“We are not broke or bankrupt as a State; we have been looted,” Frangieh clarifies. “Our public funds have been stolen and the economy is collapsing, so all services are deteriorating and are no longer available to all citizens on an equal basis.”

Throughout the past two years, the passport renewal process has been riddled with obstacles from overnight queues and long delays because of understaffing or malfunctioning equipment, to changing requirements, exorbitant fees, and most recently the unavailability of appointments.

But this won't stand in the way of leaving for people who were let down by decades of economic failures. Hmouda, a Tripoli survivor, is resolute.

“God knows how [but] we’ll get out of this country… [whether] by land, air, or sea.”