Samidoun: Lessons From the Civil Resistance to the 2006 War

Editor’s Note: Despite sharing similar names Samidoun and the Samidoun Prisoner Solidarity Network are different organizations.

During the 2006 Israeli war on Lebanon, a new form of civil resistance emerged from what was at the time a marginal radical left. Over 33 days, the duration of the war, this resistance mushroomed from a small group of activists and revolutionary socialists into a network of thousands of volunteers supporting tens of thousands of people displaced from south Lebanon and the southern suburbs of Beirut.

Samidoun, meaning steadfast in Arabic, was hailed as a “remarkable social welfare movement” and a model for self-organized civil response to war and crisis. Its organizers say that it was not a bottom-up NGO or simply a humanitarian response in time of need, but a highly political and a strategically placed civilian arm of the armed resistance to the Israeli war.

As another Israeli war on Lebanon darkens our horizons, The Public Source tells the story of this movement: how it mobilized practical aid for the war effort, overcoming sectarianism, and protected civilians whom the Israeli occupation forces targeted as part of its military strategy.

Much has happened since 2006, from the 2011 revolutions and their defeats, regionally, to the experience of October 17 and the economic crisis, locally. Much has also changed since 2006. The resistance has become more integrated into the sectarian political system than at any point in its history. Syria is no longer an option for refuge as it was in 2006. And, in the absence of a solidarity movement today, war profiteers are stepping in to exploit the displaced by charging high rents.

Despite these political and historical differences, the underlying principles for Samidoun’s re-emergence remain the same: a political relationship between civil and armed resistance; a central role for the radical left in mobilizing wider resources in society; and democratic organization.

The experience of Samidoun, and its lessons in self-organization, show that a movement of solidarity can break the impasse of crisis.

We spoke with Ghassan Makarem, Walid Abu Saifan, and other organizers about Samidoun's strategy and tactics, and the lessons we draw from the movement. Others involved in Samidoun have contributed to this story, but wish to remain anonymous.

A poster for the July 12, 2006 sit-in organized in solidarity with Gaza by three different non-aligned groups of students, who then became Samidoun. It reads: "Wednesday, July 12, 2006 open sit-in. Starting at 3 p.m. Rejecting silence and inaction, in solidarity with the Palestinian people."

As the first bombs fell in Israel’s 2006 war on Lebanon, an extraordinary movement of solidarity rallied around those who were escaping its murderous barrage. People showed up through hundreds of thousands of individual acts of kindness. Some opened their homes and provided food and clothing, often to families from across the old sectarian divide; towns and associations stepped in to support the displaced; and medical professionals formed special teams to care for the sick and wounded, working alongside the Lebanese Red Cross and other emergency services.

These mass acts of solidarity would blunt the edge of Israel’s offensive and contribute to its defeat. They compromised one of Israel’s key military strategies: targeting civilians to undermine support for the resistance and suppress it.

One organization stood out, Samidoun. This solidarity movement was launched on the day that the war began. It was rooted in a tradition of self-organization in Lebanon, woven like a thread through the country’s long history of crises and wars.

Lebanese revolutionary socialist Ghassan Makarem was one of its organizers. “Samidoun rekindled traditions of solidarity that have been around since the early 1970s, including activist groups and leftwing currents that delivered support and direction to working-class communities,” he tells The Public Source. “These come to the front whenever Lebanon descends into one of its periods of crisis.”

The idea for Samidoun emerged from a meeting between non-aligned groups of students, Attac Lubnan (the local chapter of the anti-globalisation movement), the left-wing group Tajamou‘ Yasari (Tymat), and independent Palestinian activists.These groups came together to actively prepare a sit-in and a solidarity action with Gaza, which was under bombardment.

“Samidoun rekindled traditions of solidarity that have been around since the early 1970s. These come to the front whenever Lebanon descends into one of its periods of crisis.” —Ghassan Makarem, organizer

The open sit-in in Martyr’s Square, set to begin on July 12, 2006, was aimed at overcoming some of the divisions that arose following the assassination of Rafiq Hariri in 2005. The organizers wanted to build a common ground in support of Palestine and to highlight the importance of civil resistance and collective action.

Little did they know that their sit-in would coincide with the first day of the war on Lebanon.

As the first displaced families began to arrive in Martyr’s Square, the sit-in quickly transformed into an ad hoc relief campaign. Walid Abu Saifan, one of the founders of al-Yasari magazine, Tajamou‘ Yasari’s publication, remembers the mood among the activists at the time.

“Immediate problems, like where to shelter people fleeing the bombs, we dealt with in a direct way. If we needed to open a school, we simply broke the locks. We did not wait for permission,” he tells The Public Source.

On the first day activists broke the locks on 10 schools. They eventually opened some 30 schools, providing shelter for some 10 thousand people, according to Abu Saifan.

“The school janitor said he would not open the school. So I got on the phone to the government and told them I was going to bring the TV people down and show how our government was doing nothing. They told me that their decision was final. We decided to kick down the school doors and open the schools,” one activist explained in an interview from 2009.

“If we needed to open a school, we simply broke the locks. We did not wait for permission.” —Walid Abu Saifan, organizer

“After the first one we just went from school to school. We opened 10 schools that first day — each time we had to break in,” the activist continued. “The next day the government relented. They opened the schools officially because we told them we would break in if necessary.”

With more and more people displaced, the urgency of the moment trumped all other considerations.

“I was nervous, but there were… kids with no water, families sleeping in the streets. These people had traveled for five or six hours to escape the bombing. So what could we do? We had no choice. We broke in, opened up the schools and provided shelter… I'm glad we did this. It was the right thing to do,” another activist expressed in 2009.

Over the next 33 days, the scope and reach of Samidoun grew exponentially. On any given day, there were approximately 300 active people from a pool of volunteers in the thousands.

The organizers set up a central hub to collate information and plot the areas under bombardment. The hub also served as a call center to coordinate volunteers.

One woman, who was trapped under the rubble of her home with her two children, managed to get through to the call center. Samidoun volunteers rushed to rescue them.

A central hub collated information and plotted the areas under bombardment. It also served as a call center to coordinate volunteers.

Samidoun also formed patrols that wandered the streets to pick up the displaced and take them to the shelters. But finding shelter was only the first problem to solve.

“At first we were going to schools and writing down what people wanted, but it became clear that this was too chaotic… [so] we [decided] at our assemblies to specialize into teams,” according to one activist.

“I headed the medical team, even though I had no medical experience. But I was able to do needs assessments of the immediate and chronic illnesses that people had,” the activist continued. “As we got publicity, doctors and pharmacists volunteered to work with us. Eventually we had a pharmacy run by pharmacy students; a mobile medical unit run by doctors who would travel to the schools for check-ups and assessments.”

Next to the medical unit, specialized units began to form based on the volunteers’ skills and the immediate needs on the ground. “I was part of the team assessing the volunteers,” Abu Saifan tells The Public Source. “We began to ask what skills people had and how they could contribute. We directed them accordingly. Soon enough, we had a number of teams working on more specialized tasks.”

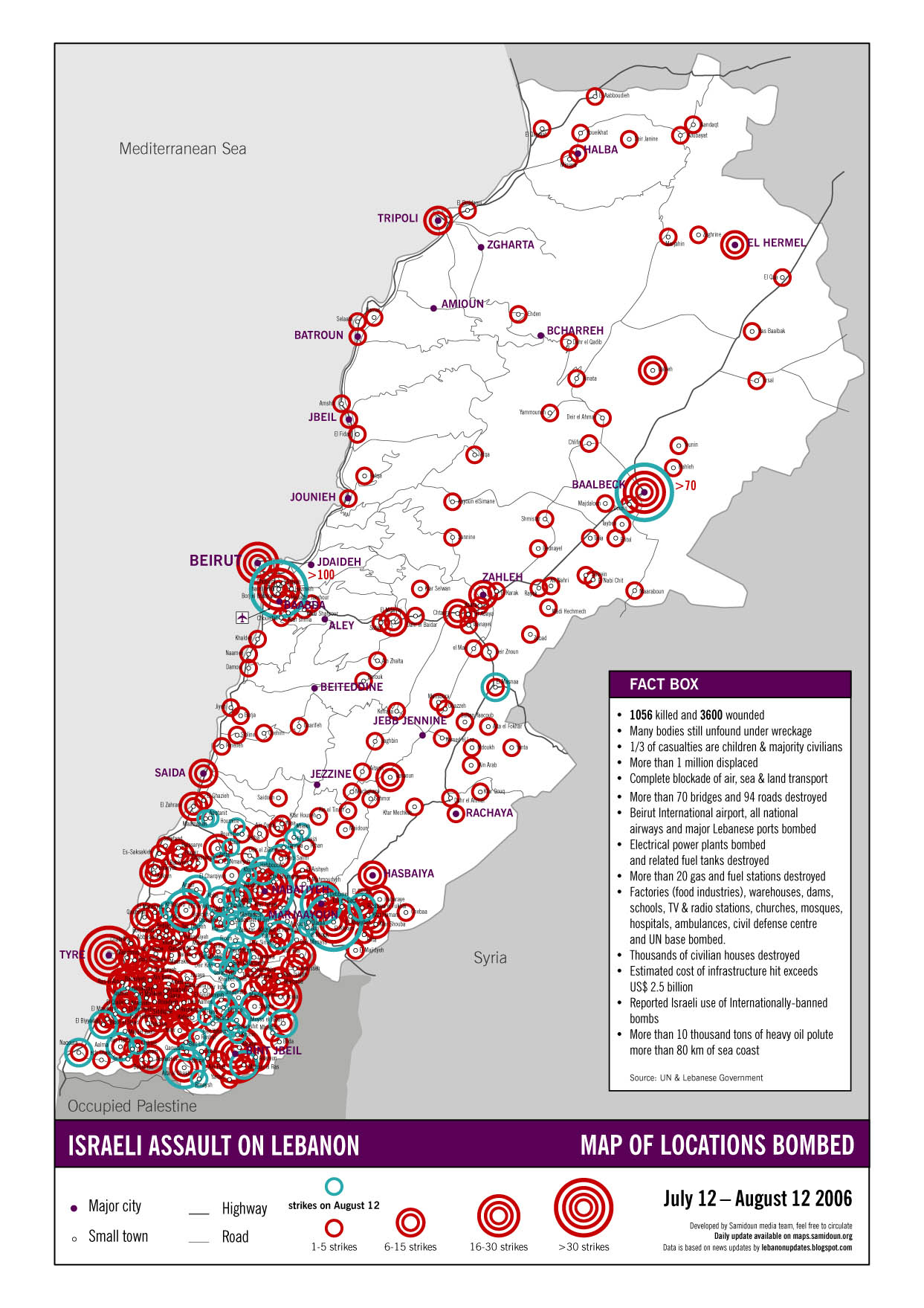

Work was then channeled through specialized units, like logistics and distribution, catering, hygiene and public health, children’s entertainment, psychosocial support, media, and administration. The media team produced detailed maps of the areas under bombardment to guide relief efforts.

One of the daily solidarity maps produced by the Samidoun Media Team, 2006. (Designed by Ahmad Gharbieh and Zeina Maasri)

“Samidoun put out a call for donations, and published contact details through al-Jadeed TV,” he recalls. “We formed an administrative group and began to collect data on the displaced, some 45,000 people out of the one million who were displaced in the war, with each person assessed for their needs. It was a very efficient operation.”

Certain businesses also joined the civil resistance. According to Abu Saifan, “Ta-Marbouta, a restaurant in Hamra, opened its kitchen, and others followed.”

The structure and organization evolved organically to meet the immediate tasks. Organizers formed two bodies: the first met every other day to coordinate daily tasks, address immediate problems, and guard against task overlap; the second sent delegates to a weekly general assembly to discuss political and strategic questions raised by the war. Both groups of delegates were elected to represent one round of meetings so that no-one could monopolize the decision-making process.

The delegates would decide on practical and immediate tasks, discuss and decide on the contents of press releases, alongside questions raised by the war, such as the nature of the resistance and how to overcome the sectarian structure of the Lebanese society.

This bottom-up approach encouraged collective decision-making without losing a sense of focus. It combined democracy in practice with centralization in action. The group’s structure was organic, practical minded, and horizontal, with speedy and flexible intervention as needs arose.

"I think Hezbollah felt that if we did this kind of work, it meant they didn’t have to; they could concentrate on fighting — and their fighters would know that their families were being looked after in Beirut.” —Bassem Chit, organizer (in a 2009 interview)

"In 2006, the state abdicated all its responsibilities, the government stopped functioning, the ministers hid in their homes,” Makarem says. “It became clear early on that the government was paralyzed; actually, it did not want to do anything. Meanwhile, activists in the Communist party were waiting for the call to take up arms, so they returned to their neighborhoods and villages. Some people within the civil society movement placed the responsibility for the war on the Shi‘a community, and wanted it to pressure Hezbollah to disarm.”

“The discussions did not end there,” Abu Saifan chimes in. “There were disagreements over the attitude to adopt toward the United Nations, which many people saw as complicit in the war. Disagreements on the question of international aid, whether to accept volunteers who belong to established political parties, and so on.”

One organizer describes to The Public Source the challenges of expanding the democratic nature of the relief work in the shelters:

We wanted each shelter to elect their own committee, but it became clear that it wasn't going to work. Shelters were all over the city; the militias and organized sectarian formations in each zone wanted a role in running them. Some of these people were very dangerous and some were very suspicious of us and what we were doing. In the Christian areas, the war marked a break with the past, in the sense that the population supported the resistance, and there were even signs of support for the Palestinians. But the organizations in these areas had to be handled with care! In parts of the city run by Amal, it was also difficult. Amal has a history of violent opposition to the Left. They worked with us, but again wanted control of ‘their’ schools and shelters. As the resistance, Hezbollah were the easiest to work with. They were concerned with the military struggle against Israel, and let us run the schools and shelters as we saw fit. But we decided in each shelter to be pragmatic: if there was an opportunity for the people to elect their own committee, great, and if people were appointed by the organizations that was fine too.

Tactics on the Fly

For all these reasons, it would be a mistake to characterize Samidoun as an aid organization or a do-it-yourself NGO, as it was highly political.

Samidoun grew from the objective circumstances of the Israeli war, in conjunction with the subjective conditions of Lebanese society at the time. These conditions included the growing secularization within social spaces, schools and universities, and friendship circles; recurring strikes in the first half of the nineties, their decline with Hariri’s crackdown on labor in the mid-nineties, and the return of a general strike in 2004; and the slow recovery of a radical left inspired by the global anti-capitalist movement and adopting the Palestinian struggle.

A process of political clarification shaped Samidoun, especially around imperialism, forms of resistance to imperialism in Lebanon, and the country’ multifaceted crisis.

Samidoun is part of a lineage of small, short-lived, radical leftist formations that emerged after the Taif agreement, like Bila Hudood, and shares with these formations similar principles.

"We wanted each shelter to elect their own committee, but it became clear that it wasn't going to work. Militias and organized sectarian formations in each zone wanted a role in running them." —Samidoun organizer

Notable among these were the rejection of the rhetoric of revolution, with its lofty slogans of Arab unity and vacuous speeches that were the mainstay of Arab nationalism; the rejection of all Arab regimes, whether royal or republican, as they served the interests of ruling classes integrated into the global system of capitalism; the rejection of any form of organizational model that was not in practice deeply democratic.

Before his untimely death in October 2014, Bassem Chit, one of the key movers behind Samidoun, explained its political lineage.

“In Lebanon, the anti-globalization protests at Seattle and the creation of the World Social Forums were very important. They helped open a space for debate and acted as a mechanism to pull activists together in Beirut, in particular. We had been so divided and so marginalized for such a long time — Seattle and the Forums were the inspiration for a new generation.”

Bassem was part of Tajamou‘ Yasari (Tymat), founded in 2001, which published the monthly magazine al-Yasari. The Assembly became the Socialist Forum (al-Muntada al-Ishtiraqi) in 2007, organized around al-Manshour magazine and the theoretical journal Permanent Revolution (al-Thawra al-Da’ima).

The group’s ideas were shaped by a formative set of principles: unconditional but critical support of all the oppressed, especially over sexuality and sexual preferences; refusal of borders as the natural boundaries between peoples; liberation as a daily practice by people and the very process to build a society in the interests of the majority.

Samidoun's approach combined democracy in practice with centralization in action. Its structure was organic, practical minded, and horizontal, with speedy and flexible intervention as needs arose.

These principles were first put into practice with the small, yet important, anti-war movement in 2003. The core of revolutionaries who formed Samidoun cut their teeth as political organizers in the mobilization against the invasion of Iraq.

At the time, there were important questions to overcome: how to mobilize alongside other forces, whether the Islamists, pro-Baathist nationalists, a section of the left that perceived globalization as a means to overcome sectarian division in Lebanon, or those who hoped that a defeat for the Iraqi regime would open up a new age of prosperity in the Arab world.

Out of these debates came the formulation of “No wars, no dictators” which combined opposition to imperialism with resistance to the dictatorial Arab regimes.

Crucially, the anti-war group that formed in 2003 was linked to that “other superpower,” the mass global movement against the war. When Samidoun presented its credentials to the armed resistance in 2006, it brought with it the credibility of this international movement.

Supporting the Resistance

Unconditional but critical support for the resistance guided Samidoun’s tactical decisions. As word went around of a self-organized civilian response, Hezbollah’s Beirut military commander called for a formal meeting.

“Our slogan was unconditional but critical support for the armed resistance, but full support for popular resistance. Our work was not humanitarian, or a bottom-up NGO work. We were part of the resistance against Israel’s war.” —Ghassan Makarem, organizer

“We met with the commander and discussed how we could work together. Of course we have many differences and disagreements with Hezbollah, but we told them that we saw ourselves as part of the popular resistance and that our task was to… mak[e] sure [people] are safe and have the resources they need,” Chit said in a 2009 interview.

He explains that they got Hezbollah’s official support, which made it easier to move and work on the ground. “I think Hezbollah felt that if we did this kind of work, it meant they didn’t have to; they could concentrate on fighting — and their fighters would know that their families were being looked after in Beirut,” he continued.

Scenes from Beirut DC's 2006 video letter called, "From Beirut... To Those Who Love Us" produced in collaboration with Samidoun. Beirut DC is a film collective and a part of Samidoun.

This united front with the resistance pulled together diverse forces to a point of shared agreement, without papering over differences, however fundamental.

“We argued that we should be part of the popular resistance, part of a united front with Hezbollah and the Communist Party who were taking up arms. We had a common goal with them: resistance to Israel.” Makarem recalls, in his interview with The Public Source, how revolutionary socialists had to convince other activists of this strategy.

“The popular resistance was an important part of the resistance movement,” says Makarem. “Our slogan was unconditional but critical support for the armed resistance, but full support for popular resistance and being with the masses. Our work was not humanitarian, or a bottom-up NGO work. We were part of the resistance against Israel’s war.”

This position was reiterated over and again. Speaking to researchers in 2009, Chit was unapologetic on this point. “War is political. It cannot be reduced to a humanitarian question, since behind its tragedies lies an open struggle…The question is fairly simple: Who are you with? With the one who assaults and kills, or with the one who confronts the aggression?”

Blunting the Butcher’s Knife

Israel’s defeat in 2006 was without a doubt the work of the armed resistance in the south. But the solidarity that Samidoun delivered in the field blunted the edge of Israel’s military strategy, the Dahiyeh Doctrine, and supported the resistance to its victory.

Named after Beirut’s southern suburb, which Israel razed to the ground in 2006 without winning the war, this doctrine’s main tenet is to harm the population, to kill and maim as many people as possible.

Israeli general Gadi Eizenkot, one its architects, explained its logic: “These [southern Lebanese and Palestinian villages] are not civilian villages, they are military bases. This isn't a suggestion. It’s a plan that has already been authorized."

This strategy assumes that once the people are terrorized, they would turn away from the resistance, or act as a restraint on it.

Named after Beirut’s southern suburb, Dahiyeh Doctrine’s main tenet is to harm the population, to kill and maim as many people as possible.

This doctrine has attempted to recreate the conditions that led to Israel's victory in the 1982 war, but on the cheap — relying on airpower without the dangers Israeli ground troops would face during an invasion. In 1982, the Israeli army marched to Beirut, trapping the resistance and civilians under a ferocious bombardment. The Palestinian resistance and its Lebanese allies eventually surrendered. The subsequent occupation of the south turned into a nightmare for the occupying power, and was eventually driven out in 2000.

This explains why the Israelis delayed the ground invasion of Gaza earlier this month. The use of “disproportionate force” — carpet bombing civilians, infrastructures, and hospitals — is central to this strategy, and is “aimed at inflicting damage and meting out punishment to an extent that will demand long and expensive reconstruction processes,” according to retired Israeli colonel Gabi Siboni.

In 2006, Israel planned to trap civilians in south Lebanon and Beirut’s southern suburb in a relentless bombardment, holding them hostage as they do today with the Palestinians in Gaza, and as they plan to do again in Lebanon when the war intensifies. Stripping Israel of this capability takes away its military advantage.

“In times of deep crisis, all the divisions within a society reach a critical point. Either we come together to face an external threat, or we fall victim to them. But how to work alongside those we oppose in other times?” —Ghassan Makarem, organizer

Fighting on the ground would be the job of the resistance, relief work that of the civil resistance, as in 2006. Because popular resistance is embedded among the people, the only way to destroy it is to destroy society. In turn, the survival of this community itself becomes an act of resistance.

Another constant in the calculations was that the Lebanese state, as a tool of divided and fractured ruling class, would be paralyzed in any emergency, more so in the face of an external threat.

On July 12, 2006, the state vanished. The government issued no orders for aid, nor did it initiate any emergency measures. It was left to ordinary people to pick up the pieces. There are little indications that the state would act any differently today, despite putting forward an emergency plan.

When The Public Source asked Makarem about the major difference between support for the resistance in 2006 and all that has passed since the 2011 revolutions, especially Hezbollah’s role in crushing the Syrian revolution, he was unequivocal.

In times of deep crisis, all the divisions within a society reach a critical point. Either we come together to face an external threat, or we fall victim to them. But how to cross this divide? How to work alongside those we oppose in other times? This is not unique to the question of Hezbollah, Fatah before them, or any other national liberation movement in history — the allegations about corruption, business interests, and support for dictatorial regimes. This is why it’s vital to operate under three conditions: first, the organizational independence of the left; second, working in a united front with other forces to confront immediate dangers; and third, maintaining unconditional but critical support for the resistance or any movement of the oppressed. It begins with a shared understanding of the immediate problem we face, the prospect of another Israeli war on Lebanon. This starting point is critical because it raises the question of how to organize solidarity across the divide.

The movement was unique because it was, simultaneously, the immediate field response needed and the correct strategy to resist and defeat Israel in 2006. Attempts to recreate it in solidarity with the Palestinians under siege at Nahr al-Bared in 2007 were met with a wall of silence and hostility. All the NGOs stood behind the army. Anti-Palestinian racism was in full force.

When the war ended in 2006, Samidoun volunteers were part of the postwar relief work, helping people return to their homes, and directing aid to the villages in the south. But once this work was over, the organizers shut down Samidoun to resume the political work that was suspended during the war, and with it a renewed criticism of the second postwar neoliberal reconstruction with Paris III in 2007, the role of the resistance, and what form it should take.

“The government was dysfunctional then, and it is 10 times worse now. We did not ask permission to act in 2006 and we will not ask permission today.” —Ghassan Makarem, organizer

If the experience of Samidoun showed the potential for the radical left to make a difference, in the years since 2006, the war on Palestinians has become more brutal. And while the 2011 revolutions showed the possibility of dramatic revolutionary change in the region, their defeat laid bare the limits of simply replacing one set of rulers with another. The movement for transformative social change has been put on pause, but the economic and political crisis today is deeper and more intractable, the deterioration of life more pronounced.

In Lebanon, the 2019 October revolution showed what is possible, but it also revealed how much further there is to go. Now Lebanon is in a spiral of crisis in which any hope of real reform, one that benefits the mass of people, cannot be achieved within the system, but only through the total transformation of society.

Yet how can this be done? There is no doubt that the movement for reform has reached its limit. It is for this reason that we need to present an organized and viable alternative for the mass of angry and disillusioned people, lest they fall victim, once again to the forces of darkness.

We have to build the institutions of revolution: committees in neighborhoods, workplaces, schools, hospitals, and so on, that can take over the day to day functioning of society. These can become the foundations for an alternative government and prove in practice how society can be organized. The experience of Samidoun proved that it is within our means and experience.

"The most important question is how to organize independently and remain part of the resistance,” Makarem says. “Samidoun proved how this can work effectively in practice. We are once again facing the threat of war, and many of those who were part of Samidoun in 2006 are beginning to organize again.”

The solidarity that Samidoun delivered in the field blunted the edge of Israel’s military strategy and supported the resistance to its victory.

With the threat of a larger, more destructive war hanging over Lebanon, and the phenomenal growth of global solidarity with Palestine, the lessons of Samidoun, and the need for an independent radical left, has become central to how we respond. The struggle against Israel and imperialism must also be a struggle for radical transformation.

“The government was dysfunctional then, and it is 10 times worse now,” Makarem says. “We did not ask permission to act in 2006 and we will not ask permission today.”