What Does Justice Look Like for the Affected Neighborhoods and Their Residents?

Cities are not like trees; despite their vitality and diversity, they cannot simply regrow when they are cut down. When a neighborhood has been destroyed, its remains dumped in a landfill, at sea, or atop a hill, its residents left shelterless, it cannot simply come back to life. And if it does, it is never the same again.

One year after the port explosion ripped through Beirut, large parts of the capital’s neighborhoods have been carved out — socially, economically, legally, and spatially — amid absolute silence from state institutions and the media, as if the repercussions of the blast are long over. In the wake of the disaster, city life picked up its slow pace and most of us resumed our daily activities, following familiar routines and unhealthy coping mechanisms inherited from past crises and wars. Not so for the residents of the devastated neighborhoods, who have been unable to return to any sense of normalcy.

Today, as we analyze the state’s response to the blast, against previous reconstruction experiences and in the context of the ongoing destruction of the city’s social fabric, we propose that full justice for the blast’s victims and for society as a whole cannot be achieved without securing spatial justice for the devastated neighborhoods.

What is Spatial Justice?

Edward Soja defines spatial justice as a “focused emphasis on the spatial or geographical aspects of justice and injustice. As a starting point, this involves the fair and equitable distribution in space of socially valued resources and the opportunities to use them. Spatial justice as such is not a substitute or alternative to social, economic, or other forms of justice but rather a way of looking at justice from a critical spatial perspective.”1 To understand how spatial justice is generated, we must see how the spatial and the social create and feed into each other, and analyze how wealth, resources, and services are unevenly distributed across space.

In this sense, a critical component is the social value of neighborhoods. A neighborhood does not become one overnight. It takes time to create and activate social dynamics, and this process can be accelerated or delayed depending on the specific contours and foundations of the space. Spaces that do not make room for the social, for community, end up turning into dead space, and can also witness violent acts aimed at transforming them (such as the example of downtown Beirut).

Spatial justice is not an unfamiliar concept in Lebanon; its absence is something we know and experience intimately. Which is precisely why we must center this form of justice in the rehabilitation of the neighborhoods damaged by the port blast. When we find ourselves discussing “reconstruction,” we must do so within a narrative of justice. We must center the mission of “achieving justice in the affected neighborhoods” in all of our work, and support their residents not only as individuals but also as a new community born out of August 4.

We must center the mission of “achieving justice in the affected neighborhoods” in all of our work, and support their residents not only as individuals but also as a new community born out of August 4.

To ensure people’s rights do not continue to be trampled — as they have been since the first moment of the blast — we must ask the right questions, address the spatial priorities of the displaced and other affected groups, and be guided by the lessons of past reconstruction projects and experiences.

What Can Lebanon’s History of Reconstruction Teach Us?

Lebanon’s multiple experiments with reconstruction can serve as a map to the questions we must ask if we are to expose the truth about how power has shaped housing policy. How has Lebanon’s power structure conceptualized reconstruction? Have residents participated in any planning processes? We begin by reviewing the most prominent of Lebanon’s reconstruction projects.

- In the mid-1970s, more than 130,000 people made their living in downtown Beirut. The real-estate company Solidere, and the law it was established under, reduced the concept of the public realm into a mere object of manipulation in the service of private interest. By pressuring residents to surrender their property and shares, by driving them out of their neighborhoods and out of the city entirely, the company stripped their negotiating power — all in order to attract a new type of capital investment in commerce and luxury housing. The process widened the gulf between social classes, exacerbated social struggles, and disconnected downtown Beirut from the rest of the city, thereby consolidating civil war dynamics.

- In the aftermath of the 2006 Israeli war on Lebanon, the reconstruction model followed in Beirut's southern suburbs was intricately tied to the dominance of one political party over the production of urban space, namely through Hezbollah’s “Waad” project. As the model strengthened sectarian logics and leaders’ influence, several towns in the South were razed to the ground instead of being rehabilitated. In fact, the contractors’ bulldozers finished what the enemy jets had started.

- Fourteen years after the complete destruction of Nahr al-Bared camp by the Lebanese army, thirty percent of its residents are still not allowed to return home due to delays in reconstruction (according to UNRWA). A large number of those who managed to go back, live in inadequate housing conditions.

Although they represent different models, these projects all lacked the supporting conditions for the residents’ return to their homes or for the neighborhoods’ recovery. In fact, they serve as proof of the inadequacy of “masterplans” in the context of violent devastation, when such plans risk alienating and excluding victims from the process of rebuilding their homes and neighborhoods, which in turn is crucial for recovery and reconciliation. In this sense, these projects reveal the dangers of following centralized, unidirectional frameworks.

Where Are We One Year Later?

In October 2020, the law relating to the protection of the damaged and affected areas and their reconstruction was promulgated. It was drafted without any attempt to draw on the lessons of the past, devoid of the necessary economic and social components, and reducing the urban solely to buildings and real estate — all in clear disregard for the concept of spatial justice. The law deprived residents from agency in the rapid restoration of their damaged buildings, it failed to clarify the compensation process, and did not prioritize housing protection. It also failed to set a path for the rehabilitation of public spaces, and to limit speculative behavior affecting the entire city. Moreover, the law did not stipulate criteria and priorities for the recovery of the most affected neighborhoods, and excluded any stimulus for economic and social recovery.

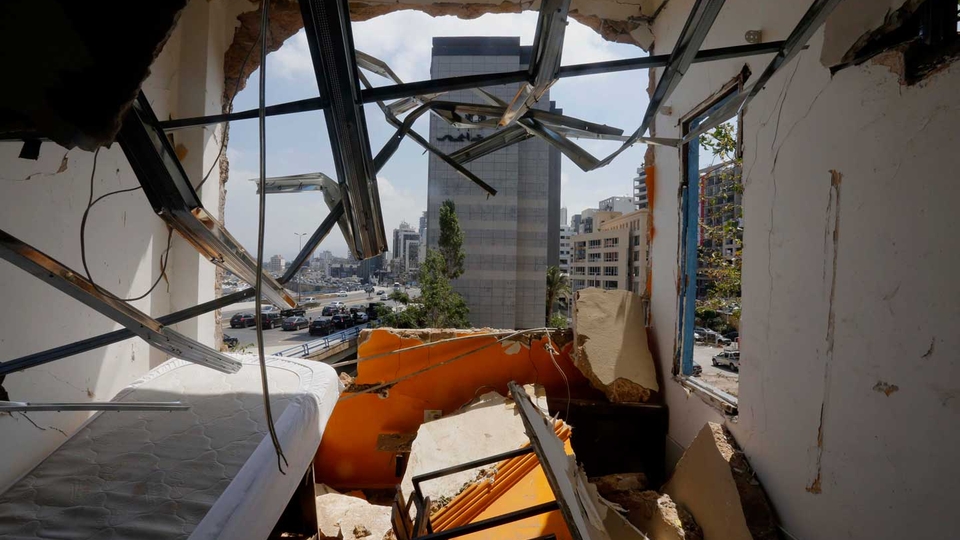

Inside the ruins of a building in Gemmayzeh. August 2020. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

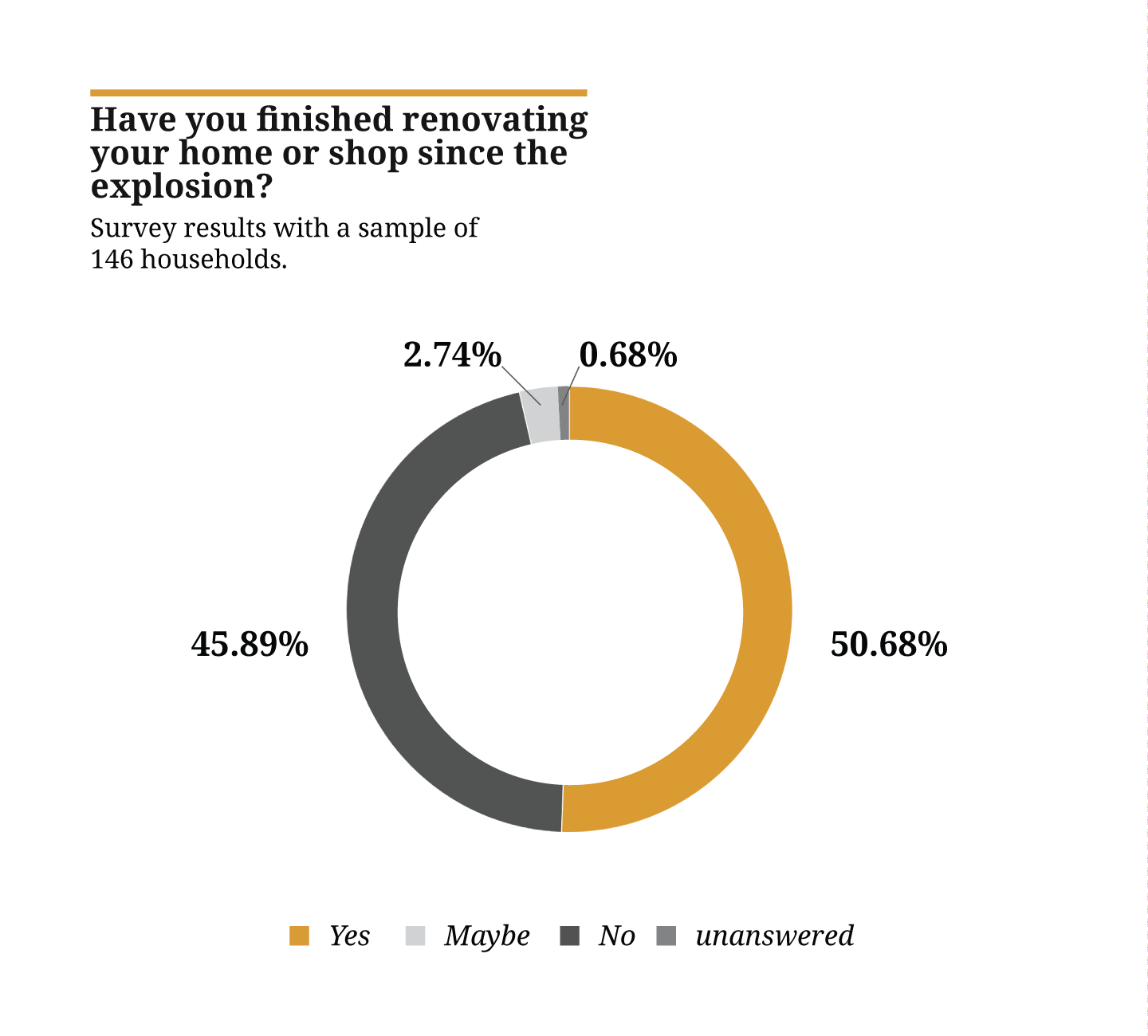

A survey we conducted with 146 residents of the affected neighborhoods between May 15 and July 15 found that 67 residents (45.89 percent) had not yet been able to complete repairs, 74 (50.68 percent) had completed repairs, 4 (2.74 percent) were unsure, and 1 (0.68 percent) did not respond. According to another recent study, only 30 percent of the residents of the most affected areas have returned to their homes one year after the blast, either because the repairs that would allow a safe return are pending or because the residents remain too traumatized.

In December 2020, the World Bank, the European Union, and the United Nations launched the Lebanon Reform, Reconstruction and Recovery Framework (3RF), an 18-month framework supported by the Lebanon Financing Facility (LFF) to respond to the Beirut Port explosion. Aiming to bridge the immediate humanitarian response and medium-term recovery and reconstruction efforts, its institutional arrangements bring together government representatives, international partners, civil society, and the private sector. Although many had their hopes pinned on this framework, these were dashed when the effort proved to be led by international organizations and donor countries, excluding public institutions, victims, and residents affected by the blast. The first 3RF consultative group meeting was co-chaired by caretaker Prime Minister Hassan Diab, Civil Society Representative Asma Zein, EU Ambassador to Lebanon Ralph Tarraf and UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Lebanon Najat Rochdi.

On April 9, 2021, four German companies unveiled a multibillion dollar project they had submitted to the Lebanese authorities for the reconstruction and development of the Beirut port and its surroundings. The proposal reproduced the Solidere model by projecting design concepts onto the existing urban fabric, without any consideration for existing social and economic conditions. Indeed, the project was a business model founded on private ownership under international management. It was one of several projects proposed by international actors, from private companies such as the French shipping giant CMA-CGM, to the Chinese and Russian governments.

These frameworks, plans, and proposals are political tools par excellence. The difference between them and what we are proposing is far from technical. We are under no illusions that the process of rehabilitating and reviving the devastated neighborhoods, from Karantina to Mar Mikhael to Gemmayzeh and Geitawi, will be anything short of a political confrontation — a confrontation we must launch while aligning it with people’s concerns in the affected neighborhoods and prioritizing spatial justice.

Exclusionary Policymaking

City residents in general, and residents of affected neighborhoods in particular, have been kept at bay from processes that affect their whole lives. Not only are they excluded from the discussion about reconstruction, but they are treated on an individual rather than a collective basis, rendering them mere “aid recipients.”

Such chronic and deliberate exclusion of people from public policymaking has exacerbated the spread of clientelism across all specters of our lives. State institutions have exhibited deliberate reticence and delay by transferring responsibility to civil associations, many of which are affiliated with political parties, and by distributing aid based on residents’ religious or partisan affiliations. The example of a damaged building on Armenia Street is a case in point. The Tashnag party renovated one of the apartments, the Lebanese Forces (operating as “Ground Zero”) renovated another one, and the Armenian AGBU renovated two floors owned by the same landlord. Meanwhile, a barber repaired his shop at his own expense and a single woman used money sent by her brother who lives in Dubai. The remaining apartments remain unrestored. “Why did these parties and associations support some people and not others?” the shop owner asked.

We are under no illusions that the process of rehabilitating and reviving the devastated neighborhoods, from Karantina to Mar Mikhael to Gemmayzeh and Geitawi, will be anything short of a political confrontation — a confrontation we must launch while aligning it with people’s concerns in the affected neighborhoods and prioritizing spatial justice.

The operation of partisan and sectarian clientelistic networks, coupled with the associations' individualized approach to dealing with residents, has undermined collective cooperation by further widening the social gap. Families not affiliated with parties or associations, or lacking influential connections, have found themselves forced to accept partisan aid, reluctantly. The most vulnerable, however, remain the non-Lebanese residents of different nationalities, among them Ethiopian, Syrian, and Sudanese, who share the same concerns and problems as Lebanese residents.

The reconstruction law passed in October aggravates and further entrenches this alienation. While it provides for the establishment of a coordinating committee to survey damages, relief and compensation, the committee lacks any representation of rights holders, those affected, and residents. Such representation would greatly improve transparency and participation in light of the public’s generalized lack of confidence in official processes, especially since the October 17 uprising.

Despite the many calls for establishing participatory and transparent mechanisms in the work of official bodies, residents remain outside decision-making centers where their fates are being sealed, only being able to access them through personal relationships and nepotism.

No Housing Protections and Rising Eviction Threats

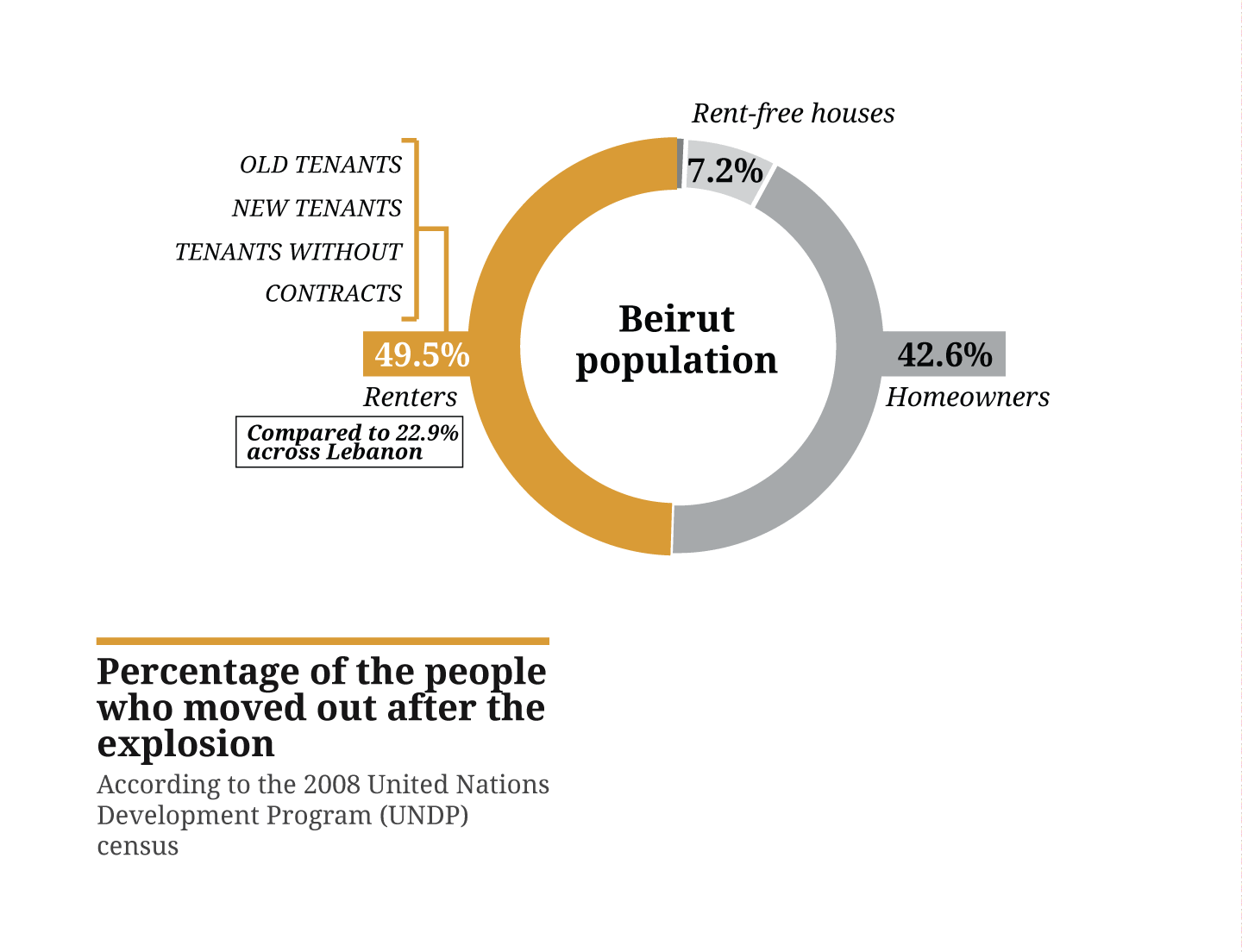

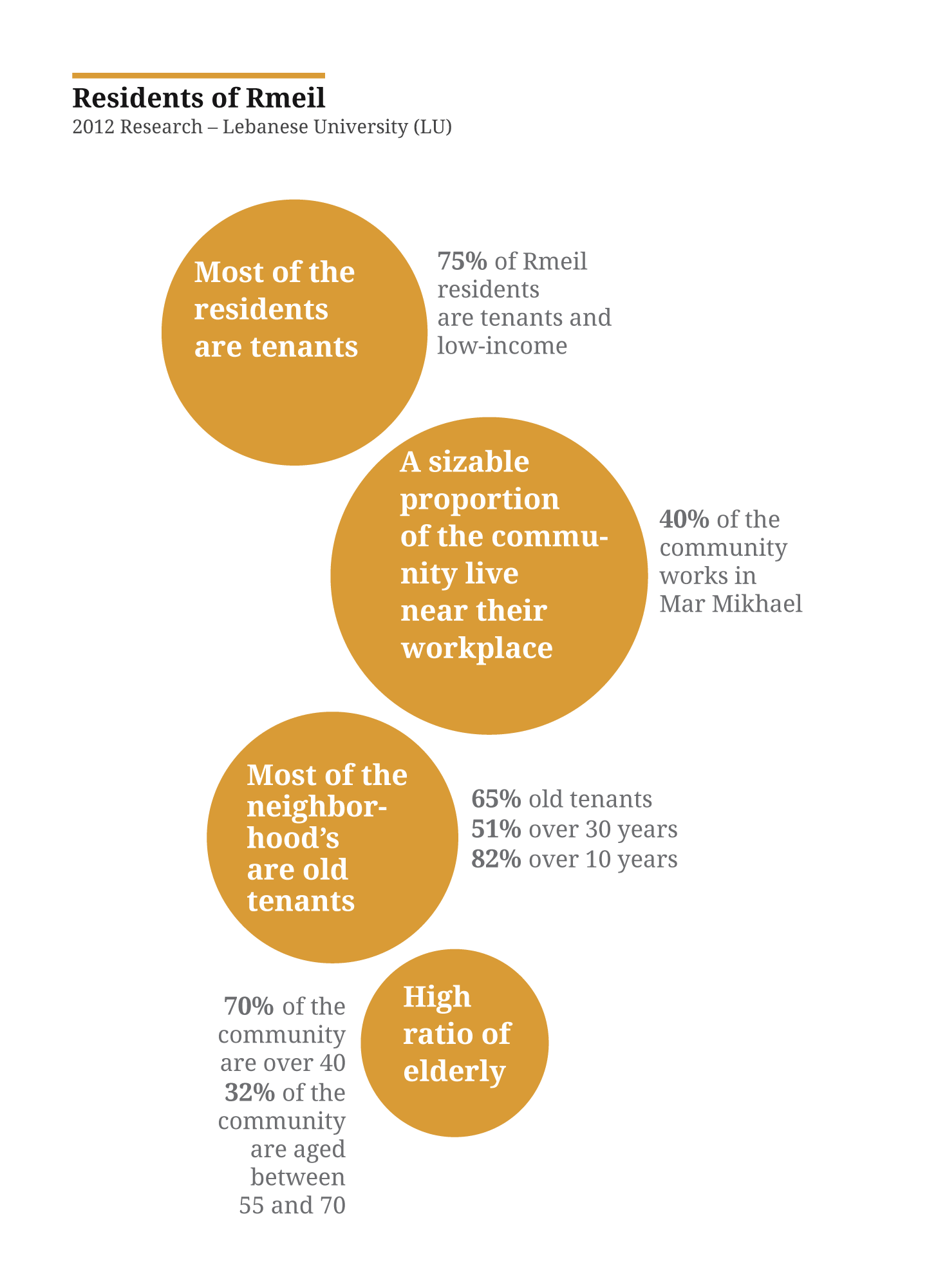

The neighborhoods destroyed by the port explosion are largely composed of old or historical buildings inhabited by a large number of tenants. Rent is a primary means of housing, as is the case across Lebanon’s main cities. In Beirut as a whole, tenants made up 49.5 percent of the total population in 2008, according to a survey conducted by the United Nations Development Program. In the Rmeil district of Beirut, 75 percent of residents are renters and low-income earners.2

The port explosion threatens this type of residents with permanent displacement amid an insecure housing situation, the complete absence of state accountability, and a legal framework that does not secure protection for the right to housing. The October law stressed the sanctity of individual property rights and the freedom of contract (within the framework of free market economics), while ignoring the right to housing as a basic right. The law does provide for the extension of residential and non-residential lease contracts in the damaged buildings and properties for a period of one year, thereby protecting from eviction for one year as of the issuance of the law. Yet this period is insufficient amid the stifling economic, financial, and social crises plaguing the country, and given that building restoration is a lengthy process, especially considering the murky and slow path of compensation distribution.

Moreover, the authorities have failed to provide alternative housing while repairs are pending. The state left the residents who lost their homes, especially the most vulnerable groups, such as those with low income, people with special needs, and the elderly, exposed to homelessness and obliged to bear the burden on their own.

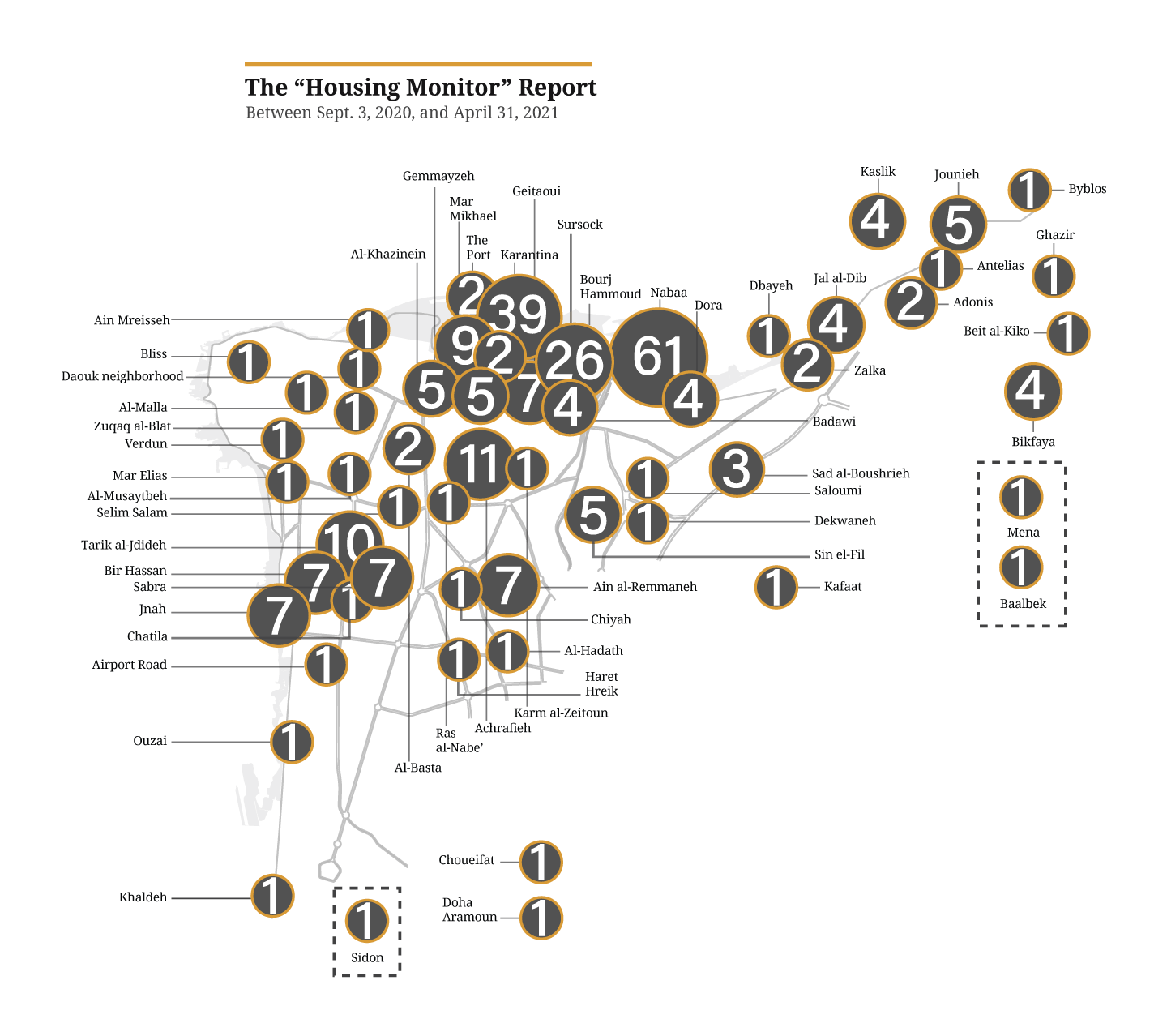

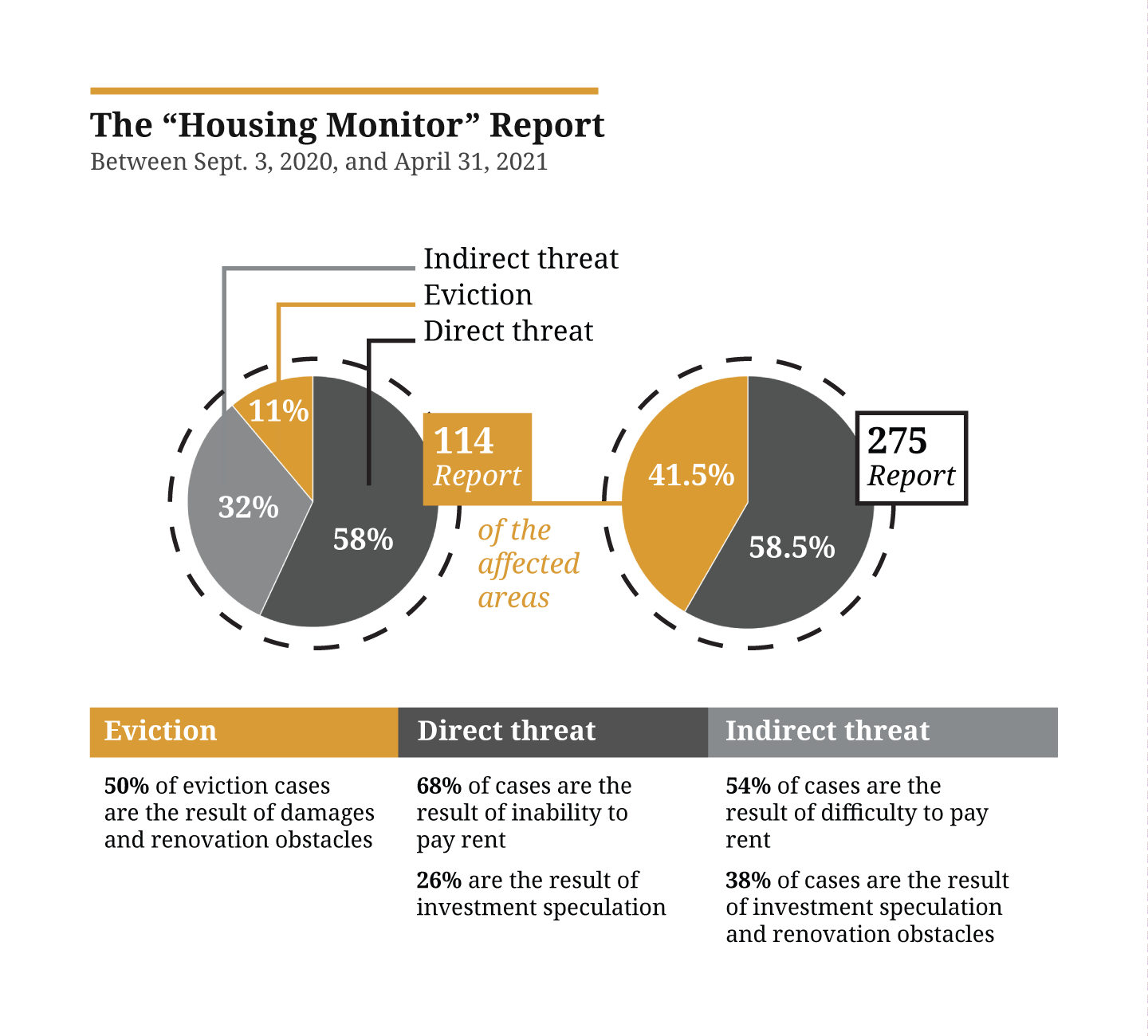

As a consequence, evictions in the neighborhoods affected by the explosion increased, most notably because of tenants’ inability to pay rent. The periodic report issued by the Public Works Studio’s Housing Monitor mapping eviction threats between September 3, 2020 and April 31, 2021, tracked 275 eviction threats affecting 939 people in different neighborhoods of Beirut. Many of these eviction threats — 114 cases or about 42 percent of all threats — were in the affected areas. Of note, a large number involve new non-Lebanese tenants, namely Syrians and foreign workers, who are the most vulnerable to eviction pressures given their fragile legal situation.

Eviction threats come in many forms: landlords increasing rent upon the completion of repairs paid for by associations; attempting to confiscate allocated aid before it reaches tenants; refusing to repair or to allow tenants to repair themselves; attempting to terminate the lease or refusing to renew it in the aftermath of the explosion. Unfortunately, eviction threats were not limited to verbal threats; some involved physical violence and forced evictions that have been carried out, exacerbating the suffering of the residents who survived the horrific blast with its physical, material, and psychological damage.

Many tenants were evicted or permanently relocated. Some of them left permanently before the end of their written or oral contract, unable to bear the costs of renovation or the psychological trauma, or because they did not believe that repairs would ever take place. Many of them were unwilling to pay for the repairs, given that the law allows landlords to evict them after repairs are completed, either by increasing their rent or simply refusing to renew the lease.

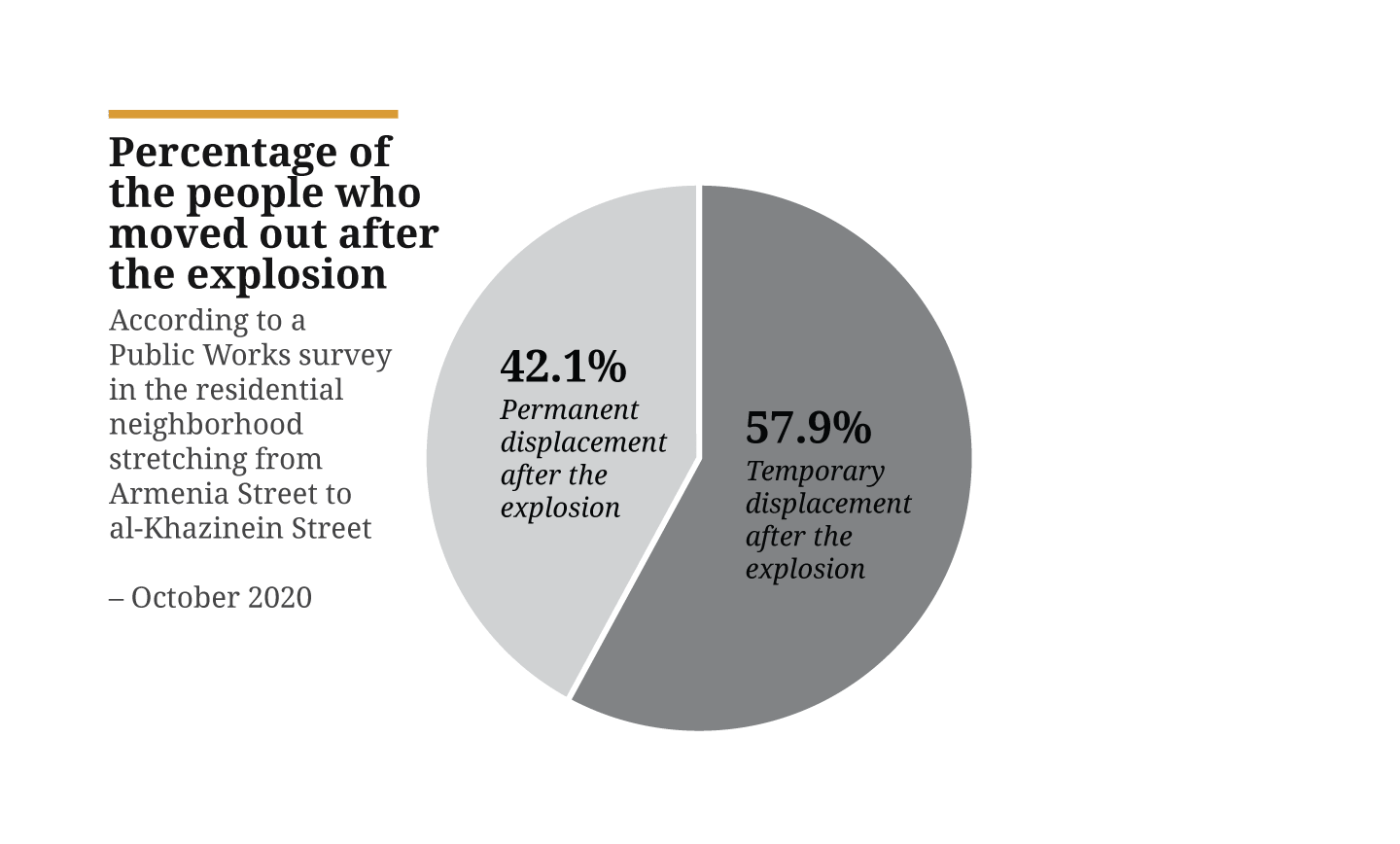

Meanwhile, the rapid, temporary relocation necessitated by the blast risks turning into permanent displacement. In a survey we conducted on a sample of a residential neighborhood stretching between Armenia Street and al-Khazinayn Street, in October 2020, we found that about 42 percent of apartments were permanently vacated, compared to 58 percent classified as temporarily vacated until the completion of repairs. These evacuations and eviction threats seriously undermine the recovery of Beirut as a viable city with thriving sources of livelihoods.

Real Estate Speculation

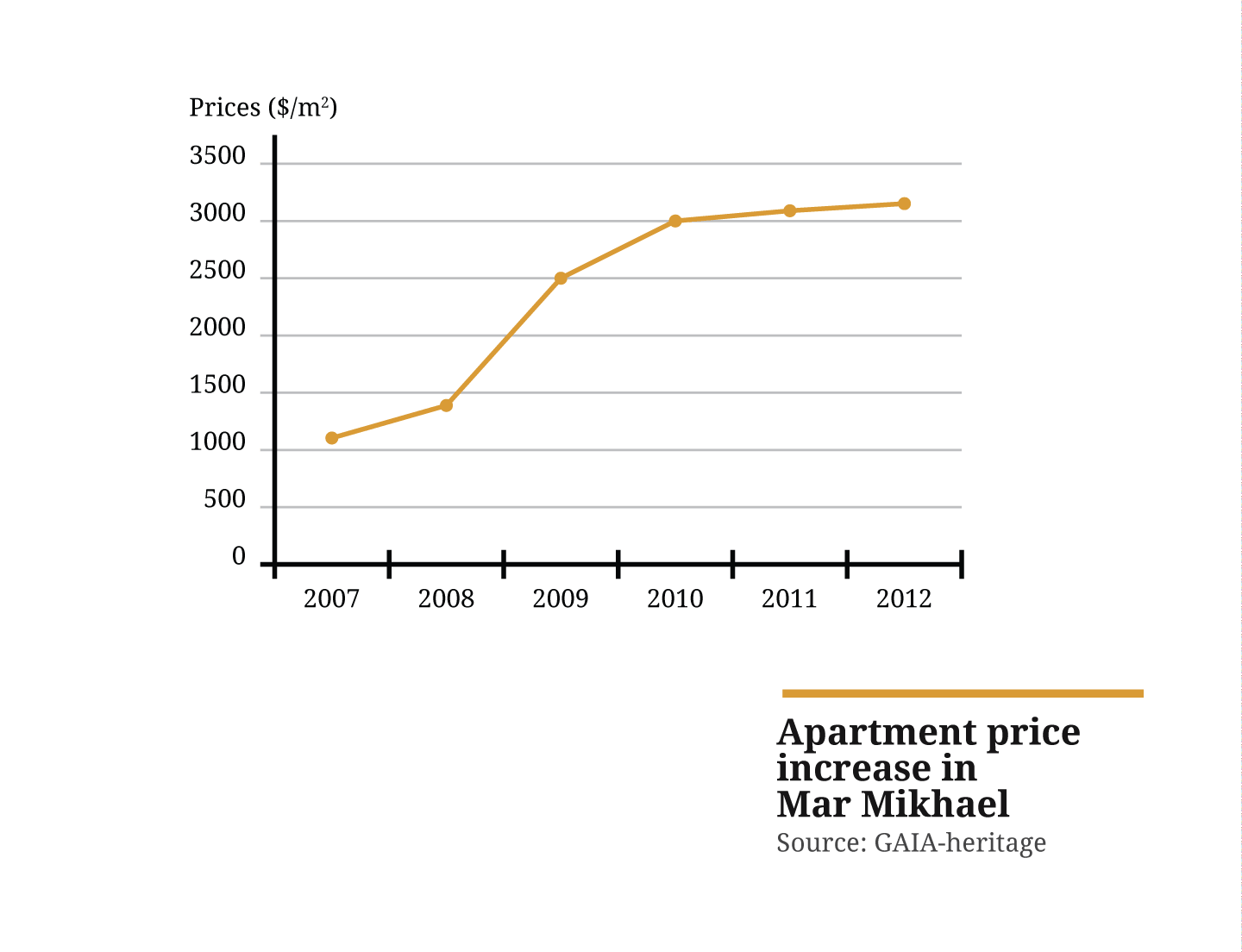

Although cases soared after the blast, evictions are not new to these neighborhoods. The Mar Mikhael neighborhood, for example, has been undergoing gentrification since 2006, transforming it from a neighborhood built on a crafts-based economy, such as carpentry and woodworking, into one relying on tourist services. Over the years, the Ministry of Tourism granted licenses to new restaurants and bars to open their doors until dawn, in violation of the law. This economic shift inflated real estate prices and rents, displacing many residents and negatively affecting the daily life of those who stayed. As the map shows, a large number of properties are now owned by real estate companies.

Moreover, residents faced threats of displacement because of the insistence of the Beirut Municipality and the Council for Development and Reconstruction, as of 2014, on implementing the “alHikmeh- alTurk” axis project (also known as the Fouad Boutros highway) under the pretext of solving the traffic issue in the area. The project would be catastrophic, as its execution requires the demolition of part of the neighborhoods and several residential buildings. In the same context, the Beirut municipality believes the Karantina area comprises valuable real estate stock that must be “invested”. These are just some of the practices that preceded the blast. Today, it is all the more necessary to address these preexisting problems by limiting real estate speculation.

A “We are staying” banner hangs from the balcony of a destroyed building in Mar Mikhael. August 2020. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

The protection measures prescribed in the new law are insufficient to achieve one of the declared objectives of the law: to protect areas affected by real estate speculation. The law prohibits the disposal and sale of real estate for a period of two years, but the prohibition excludes real estate developers, Solidere, and the owners of real estate located in the area. This furthers the privileges Solidere has enjoyed in the real estate market for three decades and expands its ability to control prices. Seen in another light, these measures also defer the real issue at hand, because they lack the necessary accompanying measures: preventing the construction of new buildings in the affected areas or facilitating the conditions for obtaining licenses to restore damaged buildings.

Residents and workers who needed to urgently repair homes and shops were confronted with challenges at every turn: the difficulty of obtaining building restoration licenses from the Beirut municipality; the fact that the right to submit a license application for repairs rested only with property owners; and the need to apply for licenses with a written consent by the owner or a judicial decision allowing the tenant to carry out renovations.3

The case of Umm Nazih coffee shop in Gemmayzeh is illustrative, located in a building that sustained structural damage. The cafe had extended the lease contract last year for ten years, until 2029. The investment company that owns the building (along with several buildings in the neighborhood) refused to apply for a restoration license under the pretext of wishing to sell, thus preventing any repairs. Although the Beirut Heritage Initiative secured funding to restore the building, the company views restoration as an obstacle to selling; the possibilities for real estate sale and speculation increase when the property is vacant and the building demolished.

The protection measures prescribed in the new law are insufficient to achieve one of the declared objectives of the law: to protect areas affected by real estate speculation.

In a related context, in an area that consists mostly of historical buildings, the Directorate General of Antiquities has been linking donations/donors to damaged heritage buildings for restoration purposes.4 However, the Directorate’s approach to heritage is devoid of the socio-economic component. The surveys on which the Directorate relies (conducted by the Order of Engineers and Architects or private associations) exclude any data or information on the residents or occupancy of heritage buildings. In the absence of such information, and given the lack of sufficient financial means to restore all heritage buildings, how can the Directorate of Antiquities determine which heritage buildings are to be given priority in restoration? We have documented many cases of buildings restored through this mechanism but which were already unoccupied or abandoned before the explosion of the port. Ultimately it is the residents of these areas who suffer the repercussions, causing serious concern about the changing demography of the area.

Adopting the Right Recovery Framework

In sum, the enacted law does not establish a comprehensive, just, and sound recovery policy, nor does it address the real priorities of neighborhoods. It also exacerbates rather than remedy preexisting critical problems. In turn, the 3RF framework excludes public institutions, victims, and residents. As the community, the families of the victims, and the residents of the affected neighborhoods, it is preferable we seek to develop and impose an alternative path.

Our rehabilitation plan should ensure that residents return as quickly as possible, before it is too late. It focuses on rebuilding the economy and society in the affected neighborhoods; not limiting the work to buildings and infrastructures but to the full recovery of neighborhoods and the restoration of daily life. Such a plan centers on what makes neighborhoods thrive, safeguards the right to housing for all, and protects residents from temporary and permanent displacement. The framework should allow for each case to be treated on its own terms, to enable every resident to rehabilitate their home, and to avoid the one-size-fits-all approach that undermines the rights of the most vulnerable. All victims and residents would be engaged in planning, organization, coordination, and implementation.

In one of his songs, the rapper Mazen El Sayed (aka El Rass) captures what happens to spaces when generations of citizens are excluded from them.5 He describes the reconstructed buildings in downtown Beirut as “biscuits,” fragile city structures that can be destroyed by the bare hands of young protesters in the context of repeated protest and confrontation with security forces. The hate young men and women expressed for these structures is not surprising, for these were spaces closed off to them, and which boasted infrastructure, services and planning utterly absent from their own areas and villages. Justice is also spatio-geographical: an equitable distribution of wealth and access to resources and services are basic rights.

Above all, cities are made up of neighborhoods, of the residents who live in them, together, of what they collectively create by interacting with, changing, and adapting to their neighborhood. Therein lies the importance of the geographical and spatial conception of justice; for it reflects the needs of residents and serves as a unifying platform for the neighborhoods' concerns, demands, needs, hopes and aspirations.

Amid the absolute absence of the state from the crime scene, various associations and entities took it upon themselves in the first weeks to survey the damage in order to begin the recovery. Timid initiatives by the state followed, but all were later withdrawn. Can we fill the public void created by the associations’ actions, and who will fill it?

Today, and specifically as a result of the explosion, the opportunity presents itself for us to impose a new reality. Just like power has always benefited from reconstruction to impose a new status-quo in its favor, we have an opportunity to impose our aspirations, but only through frameworks and structures that allow the real participation of the residents.

ADDENDUM

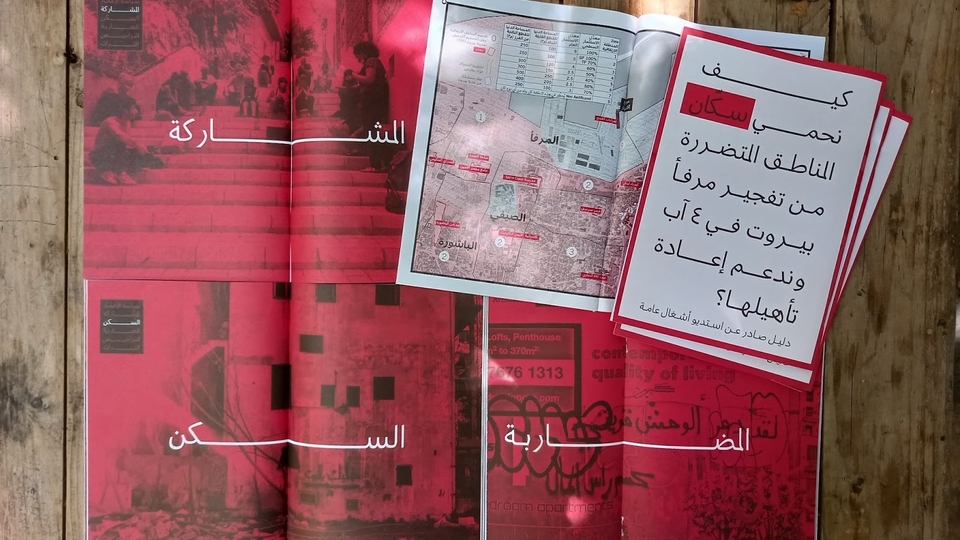

A guide for discussion between different groups, prepared by Public Works, titled “How to protect the residents of the areas affected by the Beirut port explosion, and to support the neighborhoods’ rehabilitation.” (Courtesy of Public Works Studio)

Guide for discussion between different groups

Public Works prepared a guide titled “How to protect the residents of the areas affected by the Beirut port explosion, and to support the neighborhoods’ rehabilitation,” designed to disseminate information, build knowledge, and organize the community around basic concepts and demands to move forward on the path of post-disaster urban planning based on the principle of social justice.

The guide includes some of the provisions of the Law on Protecting Affected Areas and Supporting their Reconstruction.” It sheds light on the risks entailed in the law through six sections: reconstruction policy, participation, housing, speculation, licenses, and heritage.

The guide also includes testimonies from residents and information in relation to the neighborhoods problems before the explosion and the challenges facing residents. This is not to mention recommendations developed in cooperation with a diverse group of residents during meetings held in the various affected neighborhoods. These recommendations would be used as a tool for lobbying, advocacy, and policy change.

The guide is dedicated to the residents of the affected areas, all victims, and all workers devoted to this case, as well as local and international associations in a bid to influence their work programs.

A poster of the Housing Monitor hotline, a platform to protect housing rights in Lebanon, reads: “Eviction Threats are Illegal: Report Violations”. September 6, 2020. (Courtesy of Public Works Studio)

The Housing Monitor, a Platform To Protect Residents

The Housing Monitor is a community housing tool developed by Public Works Studio to protect and advance housing rights in Lebanon. The tool is used by residents from various marginalized social groups to report on housing vulnerabilities and eviction threats. In response, Public Works Studio provides individualized legal and social services, mobilizes tenants around shared grievances, and identifies any trends in housing injustices. In doing so, it empowers marginalized city dwellers to claim their housing rights, while raising attention over detrimental housing policies in Lebanon that have affected vulnerable residents. Public Works Studio developed this project to document and report housing right violations in a country where a lack of data allows ongoing corruption, poor planning, and marginalization of low-income city dwellers; to respond to marginalized city dwellers’ housing needs with legal and social support, building rights-based awareness and establishing a direct hotline of responsiveness; to build and mobilize tenant and community member organizations based on shared housing vulnerabilities and interests; and to identify general housing trends and develop informed response strategies and policy recommendations.

A residents' meeting. July 2021. (Courtesy of Public Works Studio)

The Residents’ Gathering, a Representation Horizon for Neighborhoods

“The gathering of the residents of the neighborhoods affected by the August 4 explosion” is one of three gatherings formed in the aftermath of the explosion by the victims and residents.6 This gathering aspires to include all residents and workers in the affected areas7, regardless of their affiliations and nationalities, whether they are Lebanese, Syrians, foreign workers, or marginalized groups, whether they were owners or new or old tenants, whether their homes, shops, or workplaces have been severely or moderately damaged or they only suffered psychological damage. The gathering aims to act as a pressure force on public and official bodies, international and non-official institutions. It also seeks to provide a shared working and advocacy space for the residents and to promote unified collective action to achieve justice and guarantee rights. The gathering will endeavor to secure the right of those affected to full and fair compensation; guarantee access to information regarding investigations and reconstruction policies; preserve the residents’ rights stipulated by international and Lebanese laws; ensure joint representation of the member residents in all decision-making fora; serve the residents and cooperate with partners and institutions to provide all kinds of support; address the grievances arising from the port blast and build common positions; and work towards achieving a real recovery for the affected neighborhoods and protecting their residents from displacement.

Authors: Abir Saksouk, Jana Nakhal, Nadine Bekdache

Research Team: Tala Alaeddine, Jana Haidar, Christina Bou Rouphael

Fieldwork: Rami Sabek, Rayane Alaeddine, Rita Kamel

Design: Jana Mezher, Imad Kaafarani