Merchants of Death

Editor’s Note: The black dots (●) in the text are clickable to display documents sourced in this article.

In July 2015, Lebanon began to drown in garbage. The deregulated landfill that had been taking in Beirut and Mount Lebanon’s waste in the coastal town of Naameh, south of the capital, was full. For years, residents and protestors had demanded it be shut down for good. The government finally complied but failed to come up with an alternative. As the country’s elites haggled over the next lucrative waste management contract, streets filled with piles of garbage and overflowing dumpsters. Residents and municipal workers had no choice but to burn the towering stacks of waste. Black clouds of toxic smoke hung over the city. By late August, thousands were protesting across the country, calling for the government to find an environmentally friendly solution to the waste management crisis and put an end to corruption.

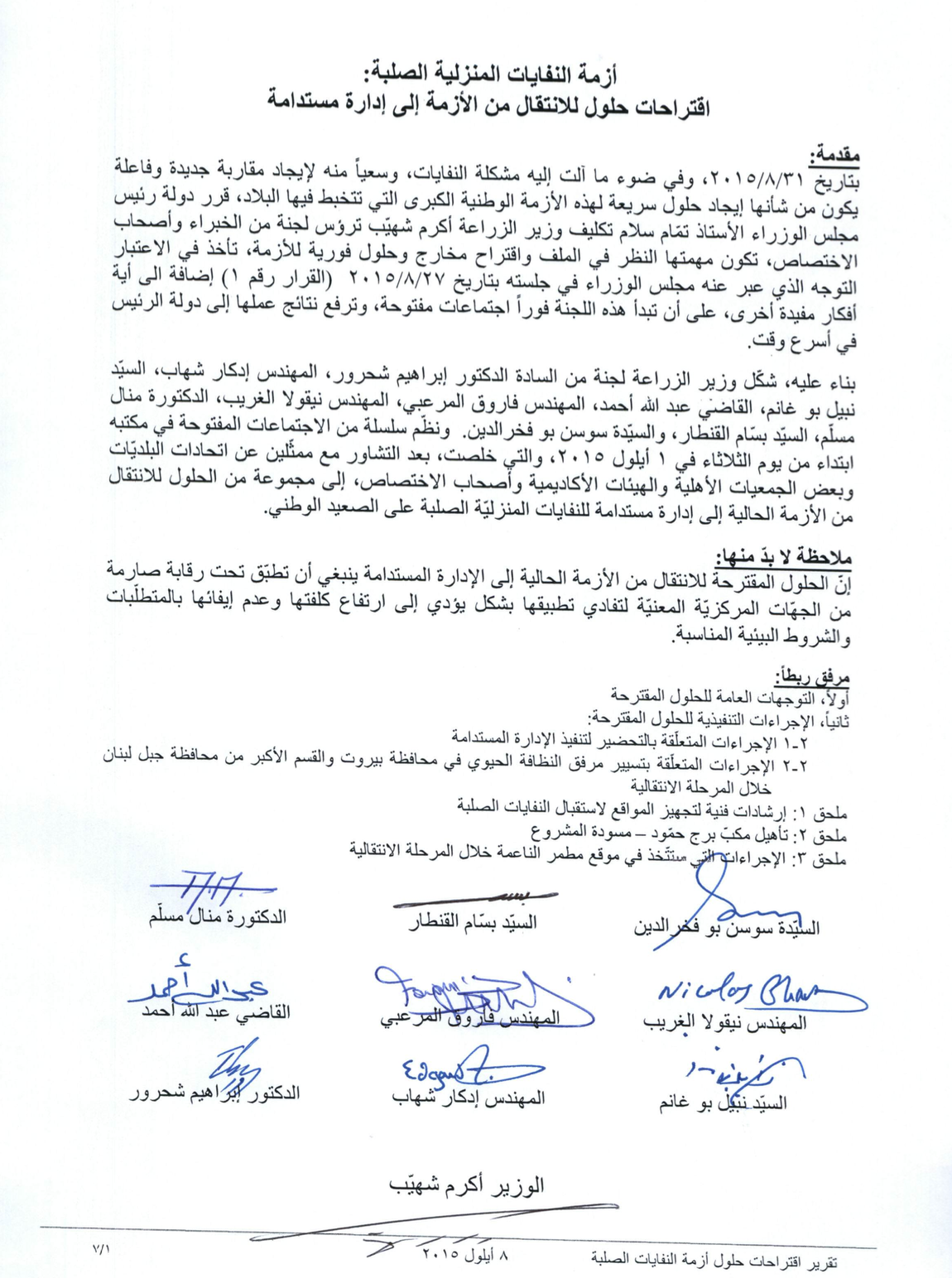

In early September, Agriculture Minister Akram Chehayeb and a technical committee of engineers and environmental experts drafted a transition plan that the government approved several days later. According to the plan, Lebanon would build new landfills, while setting up a long-term decentralized and environmentally friendly waste management system. [note:1]

One of the proposed landfill sites would be on the coast of Bourj Hammoud, adjacent to an old waste dump that the authorities closed off and left unattended for 18 years. According to citizens, scientists, and environmental activists, it contained some of the 2,000-plus tons of hazardous waste that Italian companies had dumped in Lebanon during the lawless twilight of the civil war years — and that the Italian job’s Lebanese partners, including many in high government positions, had spent years covering up [see Part I: The "Ecological Time Bombs" Unloaded at the Beirut Port Decades Ago].

According to citizens, scientists, and environmental activists, the Bourj Hammoud dump contained some of the 2,000-plus tons of hazardous waste that Italian companies had dumped in Lebanon during the lawless twilight of the civil war years — and that the Italian job’s Lebanese partners had spent years covering up.

Despite this toxic history, Chehayeb’s technical committee was especially enthusiastic about the coastal Bourj Hammoud landfill proposal. Not only would it help with getting garbage off the street, the committee said in its proposal, but it would be used to store millions of tons of waste from the old, unattended Bourj Hammoud dump that “poses significant health and environmental risks.” The land built off the coastal landfill would also be an economic bonus, through construction and development projects. There was no mention of the toxic barrels.

The Public Source obtained several government and private documents, and examined construction reports, public-private and intragovernmental documents, and reports from court-appointed experts. Our investigation found that the government was well aware of the lingering presence of the toxic waste at the Bourj Hammoud dump set to become a landfill. Once again, Lebanon’s authorities simply chose to pretend it wasn’t there.

By mid-September, when the landfill deal was final, only about a dozen protestors snaked through Bourj Hammoud’s narrow streets to protest the landfill. The Lebanese government voted to proceed with the landfilling project in mid-March 2016.

“The Most Dangerous Situation”

Setting up the Bourj Hammoud landfill was a swift process. Companies submitted bids to the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR) by June 16, 2016. Less than 10 days later, Khoury Contracting Company (KCC), whose owner is close to the Free Patriotic Movement, beat out five other companies, winning the contract with the lowest bid at $109 million. KCC got the green light to start construction on the 29th but did not sign the $109.7 million contract until August. Over the next three years, the company and CDR would agree to four contract addendums — none of which mentioned toxic waste — hiking the total cost of the project up to $142.2 million (excluding VAT).

Bourj Hammoud residents and environmental activists alike were afraid of more hazardous waste from the dump seeping into the sea. In the summer of 2016, CDR engineer Antoine al-Maouchi told local television station MTV that all measures were being taken to prevent any risks of water pollution.

But despite Maouchi’s assurances, documents and records suggest that while CDR and the contractor knew the Bourj Hammoud dump still contained waste from the Italian barrels, they never publicly addressed the waste or its toxic ramifications for the area.

While the Council for Development and Reconstruction and Khoury Contracting Company knew the Bourj Hammoud dump still contained waste from the Italian barrels, they never publicly addressed the waste or its toxic ramifications for the area.

Lebanese environmental protection legislation requires an environmental impact assessment, or EIA, prior to the approval of a construction project. The goal is to study the current environmental well-being of the area and measure the negative effects the project might have on its surroundings.

In this case, the EIA’s purpose would be to show what potential impact the landfill may have on the environment, and how to mitigate it, Hussam Hawwa, Founder and CEO of environmental consulting firm Difaf, told The Public Source. “For an issue like the toxic barrels, you would need a very specialized environmental investigation," he said. "Especially for illegal or improper works done in the past.”

The authorities, however, gave KCC the green light to start building the landfill without an EIA. The CDR did eventually issue one. But the government only received it in November 2016 — four months after the construction phase had started. The EIA made no direct mention of the hazardous waste in the garbage dump, or what risks it might pose.

People protest the government’s inaction following garbage piling up in the streets. Downtown Beirut, Lebanon. October 8, 2015. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

The closest the EIA got to acknowledging that the old dump might contain toxic waste was a reference to “potential uncertainties in the nature of some waste” and the suggestion that workers should excavate it in a “careful, progressive and scientific manner.” If the contracting company’s workers were to come across anything hazardous, they would separate, treat, and dispose of the waste “in coordination with local authorities in specially designated areas.” The technical documents of the landfill project do not mention the toxic barrels either.

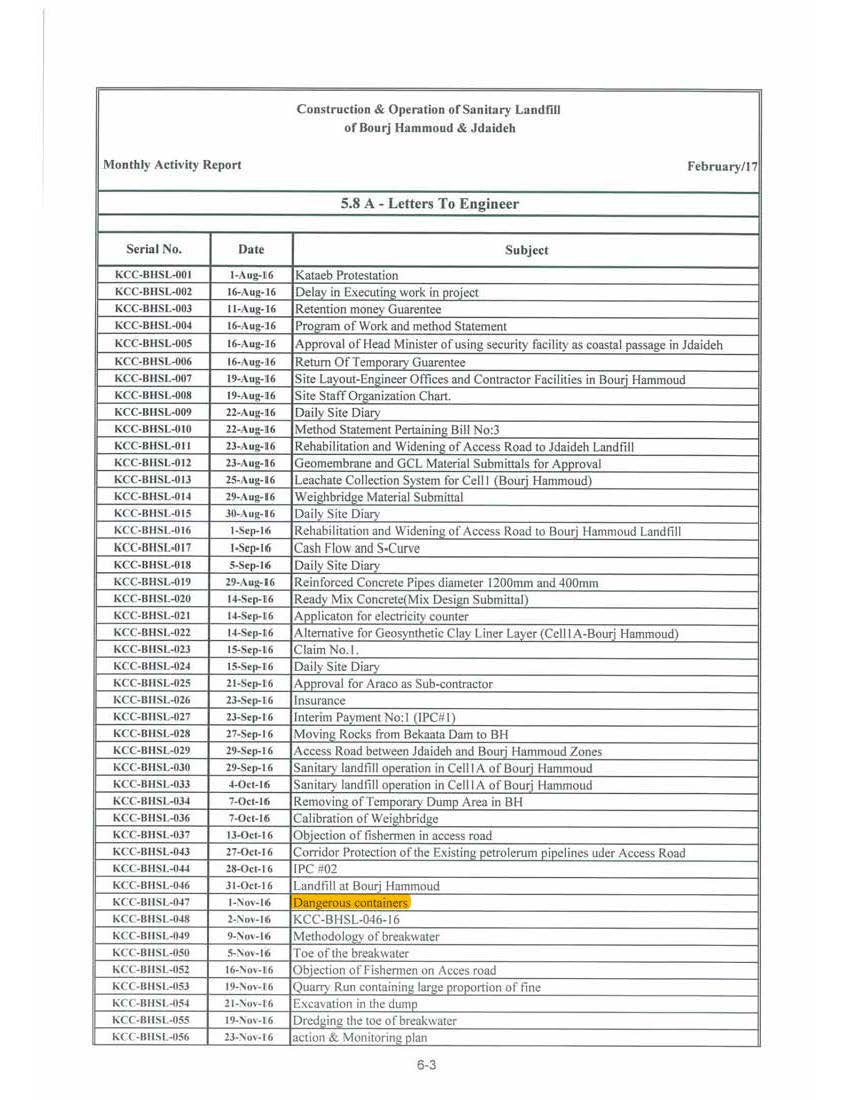

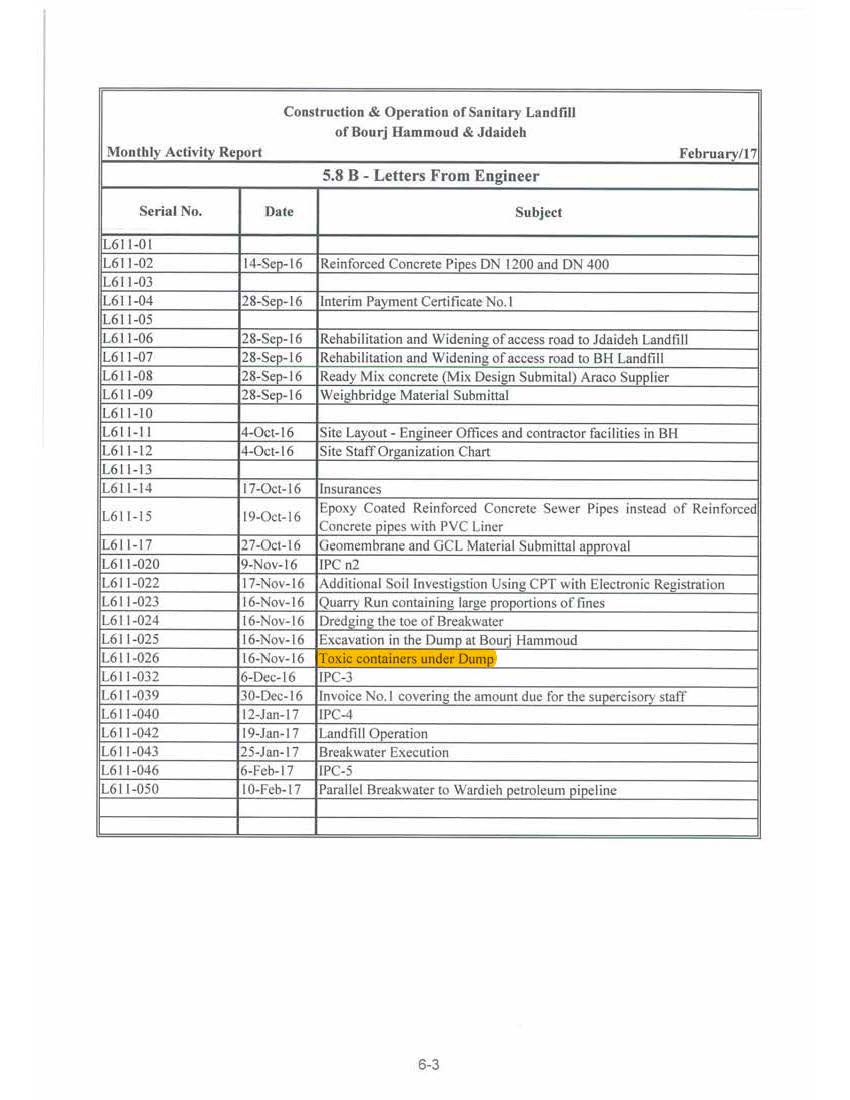

But confidential documents obtained by The Public Source indicate that KCC and other contractors were well aware that the dump contained the remnants of the Italian barrels. According to monthly reports that KCC delivered to CDR, both KCC and engineers from Rafik El Khoury & Partners — an engineering consultancy that CDR hired to supervise the construction and operation of the Bourj Hammoud landfill — had internally discussed the toxic barrels in November 2016.

The monthly reports provided updates on the landfill’s construction and operation phases. They also included scheduled meetings and a list of dates and subject lines of correspondence between KCC and Rafik El Khoury & Partners. The February 2017 report listed an email that KCC sent to the engineering consultants on November 1, 2016; its subject line was “Dangerous containers.” Just over two weeks later, on November 16, the engineering consultants sent KCC an email with the subject line “Toxic containers under Dump.” [note:2]

Staff who attended these meetings either did not respond to requests for comment or declined to speak. On September 9, 2020, a CDR official, who withheld their identity, issued a brief statement to The Public Source claiming that no toxic barrels were found during the excavation of the old Bourj Hammoud dump and the construction of the coastal landfill.

“Municipal dumps are already a disaster [even before] the addition of carcinogenic chemicals, such as cyanides, heavy metals, PCBs, pesticides, and dioxins.” —Christian Khalil, toxicologist

Dr. Wilson Rizk, the last of the three scientists who investigated the toxic barrels, told The Public Source in a 2019 interview that he remains concerned about the impact of the toxic barrels. Constructing the landfill in Bourj Hammoud without addressing and remedying the toxic waste situation first, he said, should have never happened in the first place. He called it “the most dangerous situation.”

“An Ecological Time Bomb”

To this day, nobody knows what happened to the rest of the toxic barrels that were dumped in Bourj Hammoud and other parts of Lebanon. Toxicologists Christian Khalil and Hassan Dhaini believe that the barrels most likely corroded over time, allowing their contents to seep into Lebanon’s soil and coastal waters — a scenario that could come with grave health risks.

“Some of these substances are carcinogenic,” said Dr. Dhaini, who is an assistant professor of environmental health at the American University of Beirut. “Another very important effect is that they disrupt hormones in the body and glands. Their effect is tremendous on pregnant women and impacts developing fetuses.”

A 1996 Greenpeace report describes the toxic compounds inside the barrels, most notably polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), which were commonly produced for industrial and commercial applications until they were banned in the late 1970s; and dioxins, which are highly carcinogenic industrial byproducts.

Three long months after the August 4 explosion, 49 containers of flammable substances were found in the ruins of the Beirut Port. Some have been at the port since 2009. Where these containers came from and to whom they belong is hidden.

PCBs and dioxins are both carcinogens. Both can cause serious damage to nervous, reproductive, and immune systems. The United Nations’ Stockholm Convention, which aims to restrict and eliminate the use and production of these chemicals, categorizes both of them as persistent organic pollutants; this means that these chemicals are particularly dangerous because they persist in the environment for a long time. “PCBs … actually penetrate the food chain,” said Dhaini. “They can come back to us through [ingesting] food or animal derivatives.”

Dioxins are especially persistent, according to the World Health Organization; with a half-life of seven to 11 years once they enter the body, these compounds are “among the most toxic chemicals known to man.”

A “river of trash” consumes a main road near residential areas in Jdeideh. Lebanon began to drown in garbage in July 2015, after Naameh coastal landfill began to overflow, and authorities failed to provide alternatives. Jdeideh, Lebanon. March 21, 2016. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Dr. Khalil, a professor of environmental toxicology and health at the Lebanese American University, pointed out that municipal dumps and landfills pose health concerns even if they only contain regular household waste—let alone carcinogenic chemicals.

“Municipal dumps are already a disaster,” he said. A dump with industrial and other hazardous waste, he added, is an “ecological time bomb.”

Dr. Khalil believes that PCBs and dioxins from the late 1980s would still be traceable to this day in fish and sediments. “You’re going to see some carcinogenicity in fish and in people eating the seafood from that area,” he said. “It’s going to stay in the environment for a very long time.”

Beirut’s Second Bomb

In September 2016, Hasan Bazzi and four other activist lawyers sued KCC. They called for an investigation into the landfill to verify that the old dump does not contain hazardous waste, and that the landfilling process was environmentally friendly and not polluting the sea. Metn Judge of Urgent Matters Ralph Karkabi appointed chemist Jihad Abboud to assess the situation.

Abboud submitted his report two months later. After “verifying neglect in the work being done without taking environmental and health standards into consideration,” he concluded that the landfill poses an environmental and health risk. The chemist called on KCC to “temporarily halt excavating the garbage mountain [the old dump]… until it is confirmed that there are no radioactive or toxic barrels in the dirt and after their removal.” [note:3]

Judge Karkabi did not implement Abboud’s recommendation, and the company continued excavating the old dump.

“They send [these wastes] here, probably from Europe... and they just dump them here in Lebanon [because] it’s cheaper than sending them to proper facilities to dispose of them.” —Christian Khalil, toxicologist

The lawyers decided to take matters into their own hands: they tried to collect soil samples from the dumpsite to test for themselves. But Bourj Hammoud municipal police barred them, and the scientists who joined them, from entering the dumpsite. It was an unsettling echo of previous decades, when Lebanese authorities obstructed scientists from accessing the dump for testing, and treated scientific evidence-gathering as a criminal act.

Even Lebanon’s Environment Ministry, which had helped cover up the scandal back in the 1990s, was concerned about the landfill. Throughout much of 2017, ministry officials sent letters to CDR, which The Public Source obtained. In one of the letters, officials urged CDR to “get rid of all hazardous waste” from the old dump before landfilling it. In another letter, they complained about the environmental impact assessment not being clear enough on how to handle hazardous waste, and asked to conduct tests on samples from the old dump. CDR responded by simply disagreeing with the Environment Ministry’s concerns and recommendations.

By December 2018, the court case was stalled. The Kataeb Party, whose lawyers had joined the case, called on Judge Karkabi to step down, amid mounting allegations of corruption and political interference. He eventually withdrew on January 29, 2019. The case has since come to no conclusion.

In a separate case, MP Paula Yacoubian took legal action against KCC for violating its contractual obligations by dumping unsorted waste from the old dump into the coastal landfill. She testified to Mount Lebanon Public Prosecutor Judge Ghada Aoun in late June 2018. Yacoubian’s case also stalled. She told The Public Source in a July 2019 interview that she is confident the case would resume soon. It still hasn’t.

As recently as October 2020, the Lebanese government continued to talk about the Bourj Hammoud landfill in terms of expanding its capacity. And in August 2022, municipalities, security apparatuses, and CDR met to find a “lasting solution” to recurring confrontations at the landfill between formal and informal workers that had led to the death of a waste picker. To this day, the remnants of the toxic barrels and their contents are still not on the agenda.

“Holding anyone in power to account in one case will cause others to unravel, and they [the rulers] will not allow this to happen.” —Joelle Boutros, researcher

Today, 35 years after the poison ship Radhost first docked at the Beirut Port, no one has been held to account for this ecological crime. While the Lebanese authorities initially charged the perpetrators with “collective massacre and ecocide," everyone charged walked away scot-free, thanks to Lebanon's 1991 Amnesty Law.

In 2013, another deadly cargo, this time of ammonium nitrate, would come into the Beirut Port aboard the Moldovan-flagged ship Rhosus. Seven years later, on August 4, 2020, it would explode. As in 1987, the perpetrators concealed the new cargo’s provenance, recipient, and intended use in order to protect those directly responsible for killing 259 people.

And that wasn’t all. Three long months after the port explosion, on November 11, 2020, the Lebanese government contracted Combi Lift, a German heavy lift transport firm, to dispose of 49 completely different containers of flammable substances, found in the ruins of the Beirut Port, some of which had been at the port since at least 2009.

Barrels of toxic waste at the Shnan‘ir quarry, near Jounieh, Keserwan, Lebanon. (© Dr. Pierre Malychef from Lab of False Witnesses for Ecotoxicological Research and Communication)

By the time the company’s team of 25 had finished the job in early February 2021, they had discovered a total of 52 containers containing 1000 tons of formic acid, hydrochloric acid, hydrofluoric acid, acetone, methyl bromide, sulfuric acid, peroxyacetic acid, and more. The port’s interim head, Bassem al-Kaissi, said he feared that “Beirut will be wiped out” if the containers caught fire. Combi Lift Managing Director Heiko Felderhoff told Germany’s NTV that it was “Beirut’s second bomb.”

The Public Source asked environmental toxicologist Christian Khalil about this new set of toxic barrels and their contents. “These chemicals, you cannot store them on a port in a container like that, like they've done,” he said. “On their own, they can kill. So imagine if you have a cocktail of these things together.”

The environmental toxicologist suspects that these new containers of chemical waste are probably from Europe, just like the original toxic barrels from Italy in 1987. If so, that would be a violation of the 1989 Basel Convention, which was passed when European companies got caught dumping waste in African countries — some of the same companies, in fact, that brought the toxic barrels to Lebanon in 1987.

Today, the investigation into the Beirut Port explosion seems headed in the same direction as the cover-up of the Italian barrels. In February 2021, Judge Fadi Sawan was removed from leading the probe after two ex-ministers he charged filed a complaint. His replacement, Judge Tarek Bitar, has faced a series of legal challenges from suspects in the case.

By focusing purely on negligence, rather than investigating the root cause of the explosion — who allowed the ship to dock in 2013, for example — the investigation has so far failed to address the root of the problem: the ongoing impunity of Lebanon’s rulers.

“Holding anyone in power to account in one case will cause others to unravel, and they will not allow this to happen,” says Joelle Boutros, who has researched the legal proceedings of the 1987 case. “We’re hoping the Beirut Port explosion case will have a different ending. But history tells us that these major cases never resolve, and we never find out what really happened and who’s responsible.”

Download the 2015 plan in PDF form

Download the 2015 plan in PDF form

![Excerpt of letter calling on KCC to “temporarily halt excavating the garbage mountain [the old dump]… until it is confirmed that there are no radioactive or toxic barrels in the dirt and after their removal.”](/sites/default/files/inline-images/jihad-abboud-recommendation.jpeg)