Intercepted at Sea: The Drowned, the Saved & the Missing

Editor’s Note: The black dots (●) in the text are clickable to display documents sourced in this article.

This is Part 3 of a three-part series examining the human cost of border enforcement.

On April 23, 2022, a little before sunset, siblings Hashem and Alaa Methlej boarded “the death boat” together. Minutes before they reached international waters, the Lebanese military intercepted the boat. It sank, killing half the 81 people on board. Hashem’s family are adamant that he survived. After a series of mysterious messages, they suspect army intelligence may have detained him.

A Pinch on the Ear

In mid-November, Abu Hashem got a call from the army intelligence in Tripoli. Without offering any reason, they demanded to see him the next morning at 7 a.m. Hoping to hear news of his son, he headed alone to what he thought would be a friendly meeting. He told The Public Source his harrowing account of what happened next.

When he showed up, the officers kept him waiting for hours with no explanation. “No one asked me any question,” he said. “They put me in a room, closed the door, and locked it from the outside.”

Around noon — after five hours — he knocked on the door and asked why he was being kept. “We don’t know,” an officer responded. “You’ll know soon.”

Shortly after, an officer let him out and asked about the belongings he was carrying. “Why do you want to take my belongings?” he asked. “Am I a suspect?”

When they saw that he only had his wallet, a pack of cigarettes, and a lighter, they asked him why he didn't bring his cell phone to the meeting. He had nothing to hide, he responded, but kept private family photos on his phone. They responded, mockingly: “Are we going to eat your family if we look through your phone?”

An officer told him to put his hands behind his back and to stand facing the wall. “Why are they treating me this way?” he thought to himself, surprised. Then they took his fingerprints, and photographed him from the front and both sides, like a suspect.

Around 1 or 2 p.m., they finally led him into a major’s office. The major welcomed him and asked him if he had filed a forced disappearance claim.

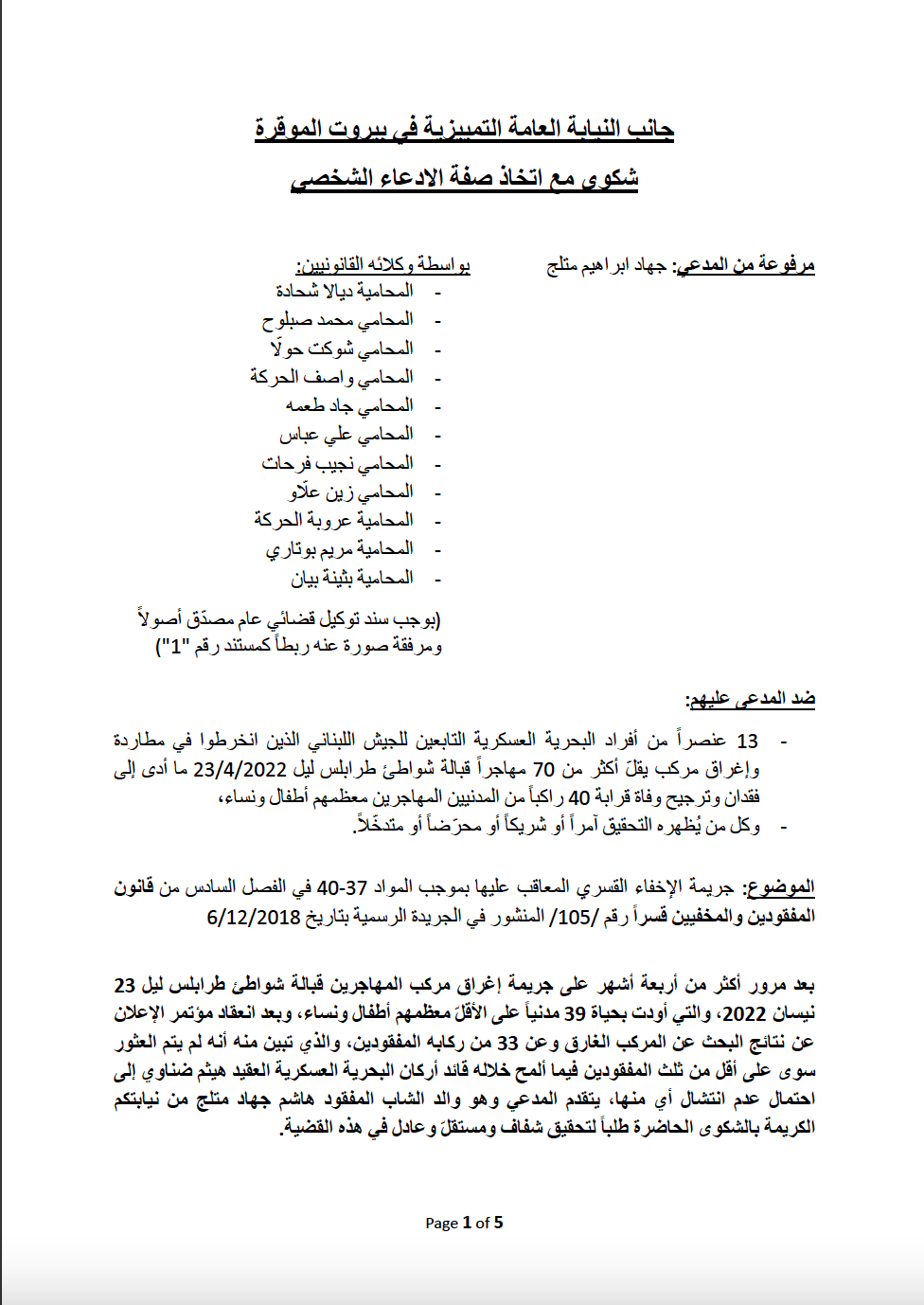

In fact, he had. On August 30, Abu Hashem had filed a claim with the same group of lawyers who had filed for al-Jondi’s release [see Part Two]. In the claim, Abu Hashem and the lawyers accused the Lebanese military of forcibly disappearing his son Hashem. [note:1]

The major told Abu Hashem he was going to the Ministry of Defense in Baabda. They handcuffed him and put him in the back of a Renault Rapid, a transport van, into something that looked like the cage they use for police dogs. When he asked if they were charging him with a crime, an intelligence officer told him this treatment was “routine.”

Are we going to eat your family if we look through your phone?” army officers told Abu Hashem, mockingly.Abu Hashem arrived at the Ministry of Defense around 3 p.m. An interrogator asked him about the complaint he filed, the evidence he was relying on, and the people who brought him news of his son. Abu Hashem told the whole story, insisting that he believed his son had been detained.

“Prove me wrong,” he told the interrogator. “It’s impossible for me to live eight months not knowing if my son is alive or dead.”

“You're right,” the officer interrogating him replied. The officer then asked him if he wanted a lawyer. Since it was late in the evening, and he was eager to go home as soon as possible, Abu Hashem declined. He answered all of their questions. Most of what they asked about was why he believed his son was alive and detained: Who called him? What exactly did they say?

Abu Hashem interpreted the interrogation as “farket adin,” a warning. “It was like someone telling you ‘Welcome’ and pinching you at the same time."Around 9 p.m., an army driver picked up Abu Hashem from the ministry in Baabda. They dropped him off on the main highway, in an unfamiliar neighborhood that he had no idea how to navigate. He walked around, disoriented, for about an hour until he finally found a bus to Tripoli. He got home at about 10:40 p.m., more than 15 hours after he left. His family and friends were frantic after not hearing from him all day.

Abu Hashem interpreted the interrogation as “farket adin,” a warning (literally, an ear pinch). “It was like someone telling you ‘Welcome’ and pinching you at the same time,” he said.

The next day he went to Mohamad Sablouh, the lawyer from the Tripoli group, and told him what happened. “The man came back to me broken,” said Sablouh, pointing out that arresting a complainant is both a crime and an infringement on the freedom of his client. “It was heartbreaking.”

A History of Obfuscation

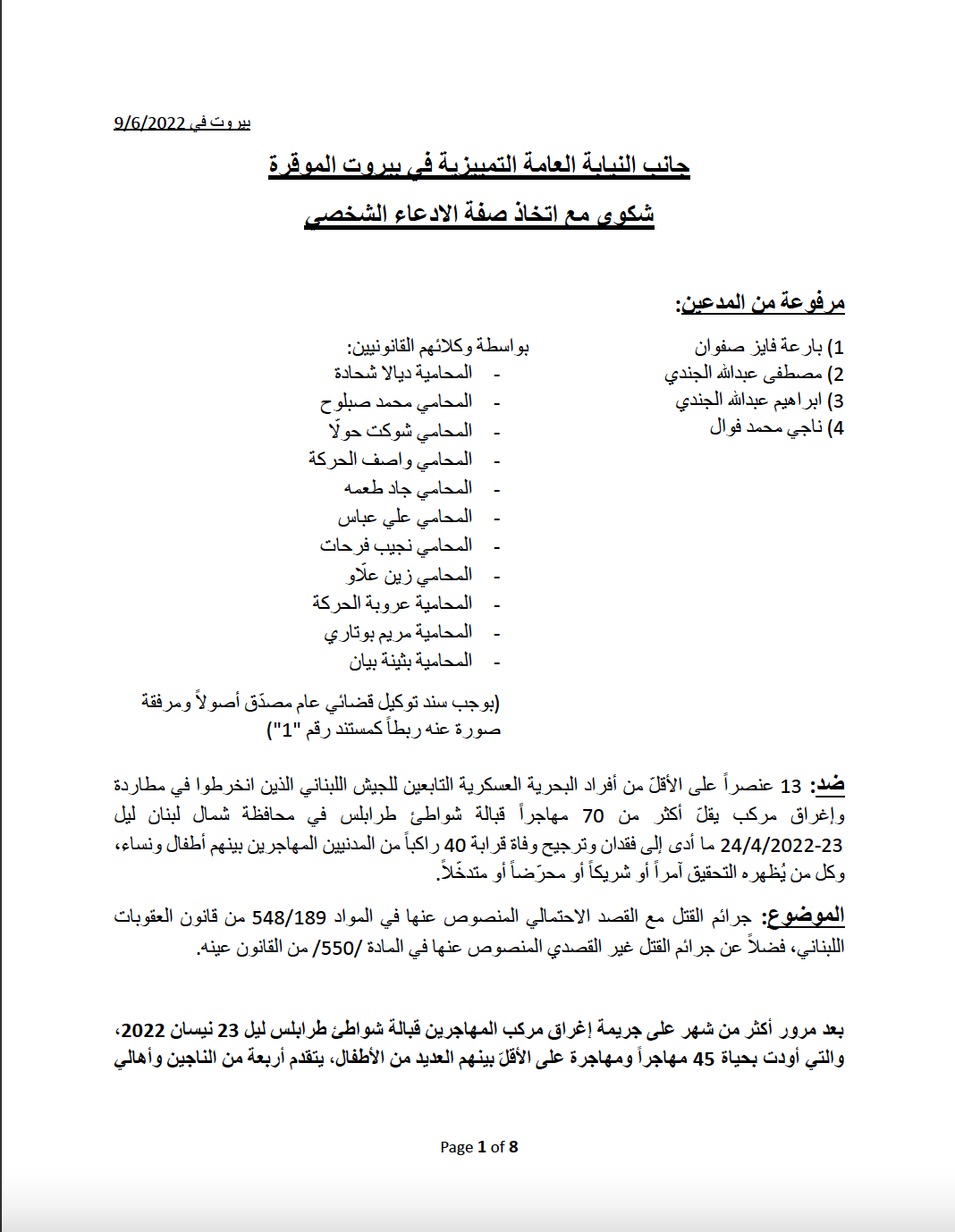

On June 6, the group of lawyers filed a complaint on behalf of Bari’a Safwan, Ibrahim al-Jondi, and other survivors from their family accusing at least 13 members of the Lebanese Army’s Naval Forces of homicide with probable intent and involuntary manslaughter. The lawyers filed the complaint to the cassation court, a civilian court. The public prosecutor then transferred the complaint to the military court. [note:2]

On June 16, the lawyers officially requested Lebanon’s caretaker minister of justice, Henry Khoury, to transfer the investigation into the boat collision and all of the civilian complaints to the judicial council, a committee of judges that looks into crimes that threaten state security.

The lawyers want the case to be heard in a court where civilian complaints have a better chance of being heard. They also point out that the Lebanese military should not be in charge of the investigation into its own navy. “In our opinion, the military court — whose investigations we cannot see yet — is not serious,” Diala Chehade, one of the lawyers on the case, told The Public Source in October. “Because six or seven months have passed since the crime, and there are still no results.”

When they first met, Chehade thought Abu Hashem was in shock from the loss of his son. But after hearing the multiple accounts of people seeing Hashem, she and the team decided to take his case.

“Prove me wrong,” Abu Hashem told the interrogator. “It’s impossible for me to live eight months not knowing if my son is alive or dead.”The forced disappearance complaint on behalf of Abu Hashem, said Sablouh, is not an accusation as much as it is asking for answers, given the contradictory information about Hashem. “We filed the complaint because there are question marks,” Sablouh told The Public Source. “Has he really been disappeared by the security forces?”

The military and the state security forces both deny detaining Hashem. Sablouh called the army about Hashem’s whereabouts and checked in person at General Security. Both responded they did not have Hashem in custody. General Security even looked up his name in their system.

Jihad Methlej has been looking for his son Hashem since April 23, 2022 when the migrant boat he was on sank off the coast of Qalamoun, Tripoli. Jihad believes his son survived the accident and is being held in detention. The inconclusive answers that he is receiving is keeping him and his family on edge, causing continuous suffering and uncertainty. Tripoli, Lebanon. October 28, 2022. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Abu Hashem's message to the army

Jihad Mthlej addresses army officers asking for answers about the fate of his son Hashem.

It’s unusual for detainees to disappear completely. In previous cases of detentions without legal notice, said Chehade, the relevant judge would usually respond within a day to forced disappearance claims. That’s what happened in al-Jondi’s case. And even when the lawyer or the family don’t know where the person is being held, they usually at least know that the person has been arrested.

In Hashem’s case, his father doesn’t even know if Hashem was arrested in the first place. “There’s obfuscation,” she said. “It’s scary.”

In November 2022, the lawyers obtained documents from the Ministry of Social Affairs revealing the nationality of all those who drowned or survived in the collision. If the government knows the victims’ nationalities, it clearly knows their names. But the ministry has so far refused to reveal who lived and who died.

The Methlej family recognizes that there’s a chance Hashem might not have survived. But given the accounts of seeing him alive after the wreck, and the absence of evidence to the contrary, they have to keep looking for him. The government’s refusal to publicly share information is adding to Abu Hashem's suspicions that security forces might be holding Hashem.

If the government knows the victims’ nationalities, it clearly knows their names. But the ministry has so far refused to reveal who lived and who died.Abu Hashem’s distrust is well founded, considering the long history of impunity and lack of transparency in Lebanon. After the Lebanese Civil War, the state set up three committees to look into unsolved disappearances. None of them gave the families of the disappeared any meaningful answers. “The fate of thousands of missing people was not clarified,” said Carmen Hassoun Abou Jaoudé, who is a member of the National Commission for the Missing and Forcibly Disappeared in Lebanon, the fourth and most recent attempt to investigate disappearances. “This is in the collective memory of people.”

Even when the authorities do release information, said Abou Jaoudé, people often don’t believe it. “Generally people don't trust the political leadership or the state institutions, in terms of protection or giving them the truth about what happened,” she said.

Today, nine months after the sinking of the “death boat,” the tormented father still maintains that his son is alive and in custody. He told The Public Source that he would be willing to withdraw his legal complaint if the authorities would let him see Hashem. “They can keep him if they want to, but give us information about him,” he said. “It is our right.”

Missing Bodies

“I’ve always loved the sea,” Bari‘a Safwan muses as she looks onto Tripoli’s seaport from her balcony one October morning. “Now I love it even more because it has my daughters.”

Safwan’s daughters, Ghania and Salam al-Jondi, 26 and 31, are among those who drowned. For a week after the accident, she would walk along the seaside, hoping for her daughters to return — or waiting for their bodies to be found, or wishing for even just a piece of their clothing to float back to the shore.

Because Safwan’s sons and daughters are Lebanese on their mother’s side, and their father was Syrian, they do not have the right to citizenship. They have to apply for residency permits every year to live in their own country. To add insult to injury, this year the government issued the sisters' residency permits after the boat collision killed them.

"The fate of thousands of missing people was not clarified. This is in the collective memory of people.” — Carmen Hassoun Abou Jaoudé, a member of the National Commission for the Missing and Forcibly Disappeared in Lebanon“When I say they’re dead, I feel ghassa1,” said Safwan in October, shivering as she spoke. “I say they’re missing.” She smoked one cigarette after the other, often rubbing her eyes to stop herself from crying.

The families of a missing person always need proof and evidence when their loved ones are declared dead, said Abou Jaoudé, who spent decades working with the families of the missing from the Lebanese Civil War. “This is why we talk about ambiguous loss, because they don't know if they are dead or alive,” she said. “The ambiguity and the waiting and waiting is torture.”

Salvage the Bones

Four months after the shipwreck, a submarine mission rekindled the Methlej family’s hopes. In the last week of August, a Lebanese-Australian immigrant named Tom Zreika hired a submarine through his charity, AusRelief Sons of Lebanon. Working closely with Lebanese authorities, Zreika announced that his team would descend to the sea floor to locate the death boat — and hopefully find some answers for the grieving families.

According to a report published by AusRelief, the mission’s goals included documenting the death boat itself and the victims’ bodies, bringing them back to the surface if possible, and reporting the findings to the families and authorities. But the team evacuated from Lebanon before completing its mission, citing “security concerns” and “anonymous threats,” and left the families with more frustration than relief. [note:3]

Four months after the shipwreck, a submarine mission rekindled the Methlej family’s hopes.To make matters worse, the navy told Zreika and international media outlets that the bereaved families themselves were behind the threats to the crew. Zreika also blamed the migrant boat for the collision, telling Al Jazeera that the two boats had collided, but “it wasn’t the bigger boat causing the damage.”

According to the report, the team tried to recover the body of one of the victims, but it disintegrated as they lifted it in the water. “By the time the submarine was lifted onto the barge, all that was left was the clothing of the deceased,” AusRelief stated. The charity did not clarify how, exactly, the team had attempted to lift the body, or why it fell apart, or if any attempt was made to identify the victim through the clothes. It’s also unclear what happened to the bones, which do not spontaneously disintegrate; if they were scattered, that would make it more difficult for the victim’s family to gather, identify, and eventually honor and bury their loved one.

For a week after the accident, Safwan would walk along the seaside, hoping for her daughters to return — or waiting for their bodies to be found, or wishing for even just a piece of their clothing to float back to the shore.On February 6, 2023, Anahon, a Tripolitan media outlet that is working with Sablouh, published a recorded call that raises serious questions about the truthfulness of AusRelief’s report. In the call, two members of the submarine’s local crew — one who gave his name, and another who remained anonymous — discuss their dissatisfaction with the mission. The anonymous voice says that the team was instructed to put back the bodies they had tried to retrieve during the mission. “It means they were intact,” the voice says. “They didn’t disintegrate.” The Public Source reached out to AusRelief for comment on the criticisms of its mission; as of press time, we have not heard back.

Ghania and Salam Al Jondi’s matching purple beds have been empty for nine months. On Ghania’s side of the room, a “LOVE” wall sticker is starting to peel off; on her bed is tied an army scarf holding up a plastic red rose. The sisters both drowned on April 23, 2022 when their migrant boat sank after being chased by the army. Their mother and brothers who survived are still waiting for the bodies to be recovered for proper burial. Tripoli, Lebanon. October 28, 2022. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

According to AusRelief’s report, the team took high-quality photo and video of the wreck and some of the drowned for an unnamed U.S.-based production company that is making a film. But the army only shared low-quality images with the families and lawyers, raising their suspicions. The report also stated that AusRelief left the remaining bodies “as-is” on the ocean floor, after consulting with Lebanese authorities, Army General and Tripolitan member of parliament Ashraf Rifi’s office, the Red Cross/Red Crescent, and “Sharia advisers.”

The charity did not clarify how, exactly, the team had attempted to lift the body, or why it fell apart, or if any attempt was made to identify the victim through the clothes. Bringing back the bodies would have been especially important for the Methlej family. If the submarine had retrieved the bodies, and the families could use DNA testing to identify their loved ones, at least they could know for sure whether Hashem had drowned or not, Abu Hashem told The Public Source. They are still holding out hope, even if the thought of Hashem’s death has crossed their minds.

“God forbid,” Umm Hashem said. “But if I could bury him peacefully next to his grandmother and cry on his grave, I would choose that over this torment."

“A Body Without Its Soul”

These days, the Methlej family is always on edge. The parents and their daughters are easily irritable. “No one has the patience to deal with the other anymore,” said Abu Hashem. Both parents told The Public Source, on separate occasions: “Without Hashem, we are a body without a soul.”

Rahaf, the 10-year-old and youngest sister, was very attached to Hashem. Every day, she stands on the balcony staring out and crying. When Abu Hashem asks her what's wrong, she says: “Someone who looks like Hashem passed by.” When the doorbell rings, she runs to open the door. When he asks her why, she replies: “It sounded like the way Hashem rings the door.”

Rahaf’s principal called Abu Hashem to warn him that she was irritable and losing interest in her education. They are trying to support her by being patient and encouraging her to participate in school activities. But they cannot afford to take her to a psychiatrist.

They are still holding out hope, even if the thought of Hashem’s death has crossed their minds.In the last few months of 2022, Abu Hashem sold off half of their furniture to be able to afford rent in their small apartment in the Baqqar neighborhood of Qobbeh. He was a day laborer; his latest odd job, which he started at the beginning of the year, was working as a security guard. He makes L.L. 600,000 per week at most and needs to provide for himself, his wife, his son Hashem, his 10-year-old daughter Rahaf, his recently-divorced daughter Mariam, and her baby.

“The days I work, we eat,” said Abu Hashem. “The days I don’t, we sleep like everyone else: without food.”

In the last week of November, Abu Hashem’s employer apologetically informed him that he might be let go soon because of his absent-mindedness and irritability at work, Abu Hashem told The Public Source. He suspects his sudden disappearance the day he was arrested was the final blow. He told his employer what happened the next day at work. But he thinks his employer might fear that this would be a recurring issue, and that the legal complaint might lead to court dates and more investigations.

“The days I work, we eat,” said Abu Hashem. “The days I don’t, we sleep like everyone else: without food.” To add to the family’s precarity, their rundown apartment building sustained structural damage during the 7.8-magnitude earthquake that hit Turkey and Syria on February 6, 2023. Cracks started to show and rocks fell off the facade and ceiling. “God forbid we lose our home, and end up thrown out in the streets,” he told The Public Source. “This is what we’re afraid of.”

Several families who were on the migrant boat that left on April 23,2022 live in Qobbeh, including the Methlejs. Tripoli, Lebanon. August 2022. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

But Abu Hashem didn’t want people to think he was using his son’s cause to beg for aid. Hashem’s absence weighs heavier than any other difficulty. “What is tormenting me,” he said, “is much more important than the question of money.”

“When you lose someone to death, you might forget with time,” he said. “But if you are hoping for his return…” He trailed off and never finished the sentence.

“If I could bury him peacefully next to his grandmother and cry on his grave, I would choose that over this torment." — Umm HashemLately, Abu Hashem has been suffering from hypertension and diabetes. He discovered this when the boat wreck occurred, when he fainted and had to be taken to the hospital. The doctors told him that stress and trauma could make his conditions worse.

“I hope that the diseases I have developed don’t kill me before I see Hashem and make sure my little girl is taken care of,” he said. “Give me my son's news and take my whole life.”

In a recent interview, Umm Hashem said she believes that Hashem is still alive. “A mother knows,” she said, with confidence.

That night, she saw Hashem in her dream. “I swear to God, mama, I am alive,” he told her.An hour earlier, she had burst into tears. “I wish for death rather than being deprived of Hashoume any longer,” she had said, choking. But now she had recovered, and was peeling potatoes to make dinner for Hashem’s cousins and friends, who had come to his home to talk to The Public Source.

One night, before going to bed, Umm Hashem did salat al-istikhara, the prayer for guidance, an invocation Muslims use before sleeping to ask God to help them resolve a particularly difficult question or dilemma.

That night, she saw Hashem in her dream. It felt real. “I swear to God, mama, I am alive,” he told her. She hugged him and kissed him.

“When I cry, I cry because I miss him,” she said, calmly, “because I'm not used to him being far from me.”

The Public Source asked Abu Hashem what he would tell his son if he could reach him. After a long pause and a deep sigh, he said: “Baba, we are waiting for you. We will keep waiting for you.”

He stopped and fought back tears. “No matter how much time passes, we will do everything possible to bring you back safe,” he said. “Don’t you think we forgot you.”