On Today's Alternative Organizing to Reclaim and Politicize the Labor Struggle

“The truck won’t pass unless it’s over our bodies!” shouted the striking women blocking the road to the Régie’s tobacco storage facility in Beirut, late in June 1946. Bowing to the forces of capital, for 40 minutes the police loaded and emptied their guns, taking aim at the strikers and unlucky passersby. They injured twelve and killed strike organizer Warde Butros with a bullet to the head — but they could not erase her legacy.

Every May first, on International Workers’ Day, calendars worldwide commemorate similar sacrifices, if not massacres, toward an eight-hour workday, fair working conditions, and social security, slogans that sometimes conjoin with resistance to colonialism and imperialism. To commemorate means “to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger,” writes Walter Benjamin. And what world do we live in, if not a world of dangers that digs graveyards for radical histories?

This May Day, a monstrous cloud looms over Lebanon’s workers, one that has been condensing for well over half a century. This May Day, a monstrous cloud looms over Lebanon’s workers, one that has been condensing for well over half a century. Since independence, and especially after the war, the Lebanese political economy has prioritized speculative real estate, finance and tourism, rather than productive economies, undermining the role of the welfare state to an ever-receding horizon until it is decimated. As a front to this engineered catastrophe, the labor movement’s go-to tactic was the strike which made up 22 percent of all political mobilizations in the postwar decade. The fragmentation of the movement then became the object of a Haririst strategy in the mid-nineties, just as the neoliberal turn consolidated union busting elsewhere. Gradually in Lebanon, writes sociologist Rima Majed, sit-ins and marches replaced strikes.

Blow after blow, the shaky foundations of the Lebanese economy crumbled, flimsy safety nets tore to shreds, and the workers fell onto the ruins. Today’s statistics, however incomplete, are disquieting. In 2020 alone, 23 percent of full-time workers in “key sectors” were laid off. In the same year, unemployment among the Lebanese soared from 37 percent in February to 49 percent in August. And although the dearth of recent Palestinian employment data stands in the way of accuracy, as of 2015, 23.3 percent of the Palestinians from Lebanon and 52.5 percent of the Palestinians from Syria were unemployed. Many Palestinians who had employment worked in the informal sector, leaving them precarious and subject to labor exploitation.

In the face of this staggering reality, Lebanon’s co-opted labor movement, embodied by the General Confederation of Workers in Lebanon, issued vacuous calls for a general strike. The dramatic decline in union membership from 22.3 percent in 1965 to 5-7 percent in 2020 is indicative of a general sentiment of distrust toward traditional unions and syndicates and exposes the urgency for alternative worker-led organizing bodies.

The dramatic decline in union membership from 22.3 percent in 1965 to 5-7 percent in 2020 is indicative of a general sentiment of distrust toward traditional unions and syndicates and exposes the urgency for alternative worker-led organizing bodies.

On October 17, the burning fires of the uprising re-ignited the spark to organize. Workers in different professions came together to challenge the influence of establishment unions to form alternatives capable of building at the grassroots to defend their members and mobilize in their interest. The Public Source spoke to Alaa Sayegh from Li Haqqi, Gemma Justo and Mala Kandaarachchige from The Alliance for Migrant Domestic Workers, Saseen Kawzally from Workers in Arts and Culture, Samiha Chaaban from the Lawyers’ Committee to Defend Protesters, and Elsy Moufarrej from the Alternative Press Syndicate. We inquired about why they came together, their organizational structures and processes, the issues they have organized around, and their current status and level of activity — against all odds.

Some of their answers were shortened or condensed for clarity.

Alaa Sayegh, Li Haqqi

Li Haqqi emerged in response to a fundamental challenge — that is, the need for grassroots, political, democratic, horizontally-operating organizations that are widespread on three essential levels: within professions and sectors, within student movements, and across geographic regions. We believe in the need for sectoral grassroots work and the necessity for this organizing to be political so grassroots sectoral organizing develops under a political roof as part of an ongoing political struggle. Li Haqqi started from a need to wage battles around which people could mobilize through participatory and democratic organizing from which we could receive popular legitimacy. We believe in direct democracy and have adopted its tools and means internally. Today, Li Haqqi organizes at the grasstors across 19 sectors and regions in Lebanon and outside it, naturally.

Our horizontal and flat organization first opens the possibility for as many people as possible to engage in the organizing mechanism and the permanent process of new grassroots formations. Second, because it is a horizontal structure, there is no hierarchical command but there are as many leaderships as possible. This makes it difficult for the state to target us and prevents auto-destruction since there is no one star or person in command that the state could intimidate or entice. Li Haqqi has the largest participation possible in direct democracy and decision-making. Therefore, you’ll find that things are always changing internally and experimentally based on people’s aspirations and daily worries. This is crucial because this ensures that our political discourse is grounded just as it raises and radicalizes the political ceiling.

Organizing at Li Haqqi is carried out through multiple committees. We had elections this year which ended just a few days ago. More than 100 people were elected to different positions within different committees: political direction and relations, economic and financial, media relations, and internal organizing. We also have working groups formed when the need arises, tackling several key issues, such as environment and health. We also have branches, or “regional roots” throughout the country, in Beirut, the north, northern Metn, but also diasporic roots in North America, Europe, Qatar, and so on. We also have roots in various sectors among engineers, students, educators, technologists, and so on. All these committees, working groups and branches come together through a yearly general assembly during which all members vote and elect members of these groups and councils. And of course, we ensure gender justice.

Gemma Justo and Mala Kandaarachchige, The Alliance for Migrant Domestic Workers

[Unlike other collectives] we have been organizing way before October 17. We were motivated because organizing runs in our veins. I think that, as a founding committee, we share the same interests and passions. We come from different backgrounds, and have leadership within us to [organize]. Since early 2010, we have toiled and sacrificed our time off work. It was not easy. After three years of hard work from scratch, we made it and formed The Domestic Workers’ Union because we need our rights here. We cannot fight alone. It has to be with someone.

A year later, we split and formed The Alliance of Migrant Domestic Workers in Lebanon in April 2016 so that we, migrant domestic workers, could have a collective voice. We wanted to be heard. This was necessary for the sake of all migrant domestic workers, especially those who are locked in their workplace and have no access to the outside world. By organizing, we can be as one. We believe that no one should be left behind in the pursuit of rights for migrant domestic workers. Now we are trying to stand tall — this season is too hard for us. We have no money nor jobs, but there is Corona. There is no medicine, there is nothing in this country for us. We have to fight alone now. Nobody can help us.

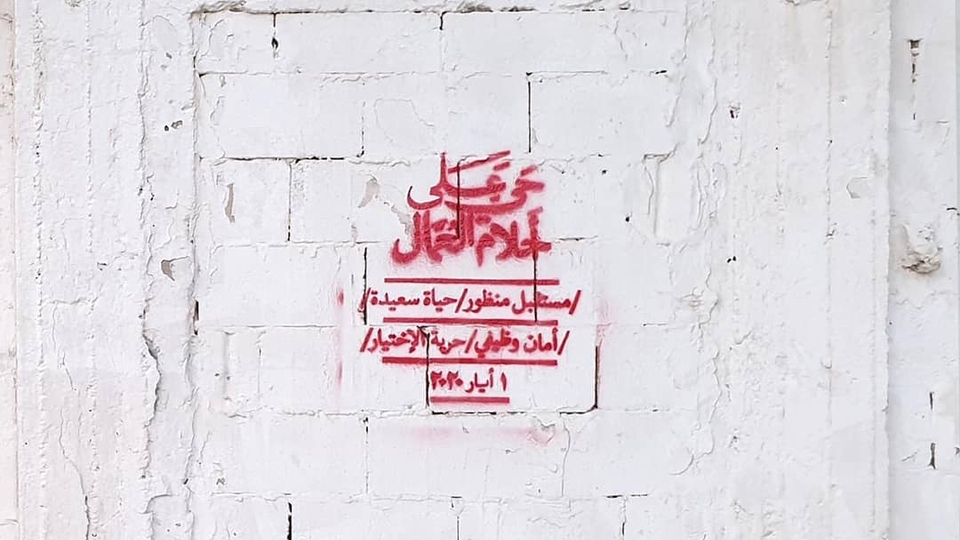

"We want bread and education and theatre." Downtown Beirut, Lebanon. March 18, 2020. (Workers in Arts and Culture)

Saseen Kawzally, Workers in Arts and Culture

The idea was to organize our sector in a politically active manner. The October 17 uprising was upon us, and we wanted to be politically involved. We wanted to organize and march and protest, not simply “make art” related to the uprising. Although we still make art of course. It’s also well known that traditional syndicates in Lebanon are extremely regressive. Barely two weeks ago, after pro-Aoun thugs attacked the home of an actor, the syndicates issued a statement emphasizing the role of artists toward “building the nation” and calling on them to respect political parties! Of course, we confronted the syndicates over their statement. There’s also the problem of corruption within these syndicates. The social security aspect of the funds they have, which comes from members dues, is rarely efficient and mostly non-existent. Many artists were left without medical coverage after the 4th of August explosion because of infighting. Even before this splintering, many who had paid member dues received no coverage or pension. Consider the case of Renée el-Dik who passed away recently. After a lifetime of acting, she died after a long battle with illness and many medical bills.

Besides the syndicates, the art scene functions within the neoliberal setting, like everything else. But it doesn’t have to and it shouldn’t. This is an important issue for us. Things get closest to liberal market practices in the plastic arts. Over the last ten or twelve years, for example, Syrian artists have been exploited by well-established art galleries; many of these bought their works in bulk and then sold them abroad for more profit. The film industry also profits from Syrian and Egyptian artists and art sector workers, especially in the technical departments, and treats them as cheap labor. Exploitation is greatest when these workers don’t have “legal” papers. Then there is the role played by arts organizations funded from abroad and the true role of art in society.

Another aspect we worked on was organizing with professionals from other sectors. Workers in Arts and Culture is part of a larger collective called The Lebanese Professionals Association which includes groups similar to ours formed of architects, doctors, journalists, university professors, and high-school teachers, etc. Covid stalled us a bit but we have been getting ready to relaunch our organizing. Meanwhile, new work groups have also been established, and we are meeting with some of them, especially theater-related groups, to discuss why cultural spaces and theaters have not been included in the reopening of the country post lockdown. We, as in Workers in Arts and Culture, are holding a general assembly in two weeks.

Samiha Chaaban, Lawyers’ Committee to Defend Protesters

The arrest of protesters started as soon as the October 17 demonstrations began. Years prior, in 2015, a group of lawyers had come together to defend the protesters during the “You Stink” movement. The Legal Agenda coordinated efforts, taking care of logistics and offering its offices for their use. [In 2019] these lawyers combined forces once again, forming a cell that gathered even more of their peers to volunteer their services as a line of defense to the protesters, especially those who had been arrested. A hotline, managed by the Legal Agenda, was established so that citizens and protesters could report cases of aggressions and arrests. Meanwhile, as many workers were dismissed from their jobs, either for participating in the protests or for being unable to get to work due to road closures, the hotline started receiving inquiries on workers' rights.

The Legal Agenda’s principle is not to leave anyone without the specialized help they need, and has committed to this principle through the working relationships it has established across the years with a number of specialized associations active on the ground. The Lebanese Observatory for the Rights of Workers and Employees is one such organization. The Agenda and the Observatory made an agreement to transfer all incoming worker-related calls to the Observatory. Within days, the Observatory established and managed their own hotline dedicated to workers, while the Agenda dedicated its hotline for calls related to protesters who were arrested.

Subcommittees formed within the Lawyers’ Committee to Defend Protesters, each specialized in a different area: one for the defense and legal representation of arrested protesters, the second for cases of torture (be they during or after the arrests by different security apparatuses), the third for the defense of small depositors and confronting the banks’ legal violations, and the last one to defend workers’ rights.

The subcommittee defending the rights of workers volunteered to support the Observatory (whose team, specialized in labor issues and syndicates, had spent years answering phone calls from all citizens seeking legal advice on their rights as workers, explaining possible legal recourse). The Observatory used to refer cases of dismissal from work to the Lawyers Committee (to handle in part or fully), as well as any complex legal questions, to ensure that workers are given accurate, legally sound answers.

Today, volunteer lawyers within the committee of lawyers to defend the rights of protesters, and particularly within the subcommittee for the defense of workers’ rights, continue to assist those who have been arbitrarily dismissed (for whatever reason), filing lawsuits (within the legal one-month timeframe to prevent workers’ rights from being revoked) and complaints before the Ministry of Labor. The Observatory continues to receive phone calls for legal advice, turning to the lawyers for background information, legal clarifications, and consultations.

Elsy Moufarrej, Alternative Press Syndicate

We organized ourselves as an alternative press syndicate since the country’s dominant sectarian political parties control the government-recognized unions, including the Press Syndicate. Our organization has two aims. The first is to represent journalists and media workers in the fight for press freedoms in the country, given the ongoing onslaught against freedom of expression. The second is to organize our first internal elections to embody our vision for the democratic representation of workers in the media sector, as opposed to the politically dominated and undemocratic processes of the Press Syndicate.

The October 17 revolution empowered us as individuals to organize under this alternative syndicate umbrella to defend freedom of expression and the rights of media workers in the country and the workplace. In the workplace, we defend workers’ rights like equal pay against gendered, ageist, religious, or ethnic discrimination. We also fight against harassment in the workplace and shed light on these violations.