Did Someone Say Workers? (Part 2 of 2)

Day 185: Saturday, April 18, 2020

On the third day of the October Revolution, I went to visit my friend and colleague Rima Majed. We were already planning research on protestors and protests which we have been dreaming about for so long. While I settle in her living room and set up my computer, I hear her speaking on the phone: “What we really need today are unions. This is the time to do it. And let’s talk to others.” "Did you say union?" I ask. "Yes" with a big confident smile, she says. I thought she was too excited to see straight.

I always studied labor organizing in “the past” and did not fathom to witness the beginning of new labor associations in the near “future,” let alone in “present” Lebanon. Little did I know that I was witnessing the rise of new labor mobilisation dynamics and one of the founding moments of the Lebanese Association of Professionals, a new labor body that is now composed of five associations of university professors, journalists and media workers, engineers, workers in art and culture, and medical doctors, aiming to reinforce existing trade unions or orders, to fill the void left by a co-opted labor movement, and to consolidate the outcomes of the October Revolution.

Social Movement Building

Created on October 22, the Facebook page “Independent Professors” invited "all students, faculty, and staff to actively participate in the protest tomorrow, Wednesday, October 23, at 12pm in front of Riad al-Solh statue." During the demonstration, Rima Majed, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the American University of Beirut, stands on a cement block during the demonstration and shouts her mobile number: “Those who want to take part in the organizing of university professors please send me a text.” Eighty professors sent their contacts on the spot and in a matter of hours hundreds of professors joined a WhatsApp group dedicated to the organizing of the Association of Independent University Professors (AIUP). On October 24, freshly organized university professors issued their first statement declaring to be on strike in support of students, staff, and professors in their protests.

“I fundamentally believe that we cannot take this Revolution forward without labor organizing. This is the platform that can maintain the social movement after the streets calm down,” explains Rima Majed.Next, the AIUP sets up a tent at Riyad al-Solh. “I fundamentally believe that we cannot take this Revolution forward without labor organizing. This is the platform that can maintain the social movement after the streets calm down,” explains Rima Majed. Meetings started to take place around the tent and discussions mainly focused on the objectives of the AUP first, and how to maintain the gains of the Revolution second. Committees were set up, and organizing work was launched. Today the AIUP holds a couple of hundred members, whose donations fund the association. The overall objectives of the AIUP is first to accompany the popular revolution and second to restore an organizational space within the academic realm by reinforcing already existing professor unions in their universities whenever possible, linking them together, and pushing for labor rights within that framework.

Organizing Fever

Inspired by the Sudanese Association of Professionals, several groups of professional groups had also been organizing outside Beirut and in different regions. They quickly joined forces with their peers in Beirut and together they formed the LAP on October 28 and issued an introductory paper stating their participation in the October uprising in protest against the political and economic system in place, refusing all ensuing social, economic, financial, and monetary policies, and calling for a democratic transition to a secular state based on social justice. The LAP then invited all professionals to join forces on all fronts of the uprising to incentivize trade unions and public sector leagues to join the uprising without hesitation.

The founding moments of different professional associations stem from accumulation of mobilizations and experiences in the previous years. One of the founding members of the Alternative Journalists Syndicate, Carole Kerbaj, told me that in the first week of the Revolution, a small group of journalists and writers gathered in a coffee shop in Hamra to set up a new organizational framework. This was not an ad hoc meeting. It hinges on incessant past discussions that gradually highlighted the need to organize in the past couple of years. “We assembled the people we knew, the people we trust, and we started. We wanted to be part of the Revolution, but this time through a labor association.”

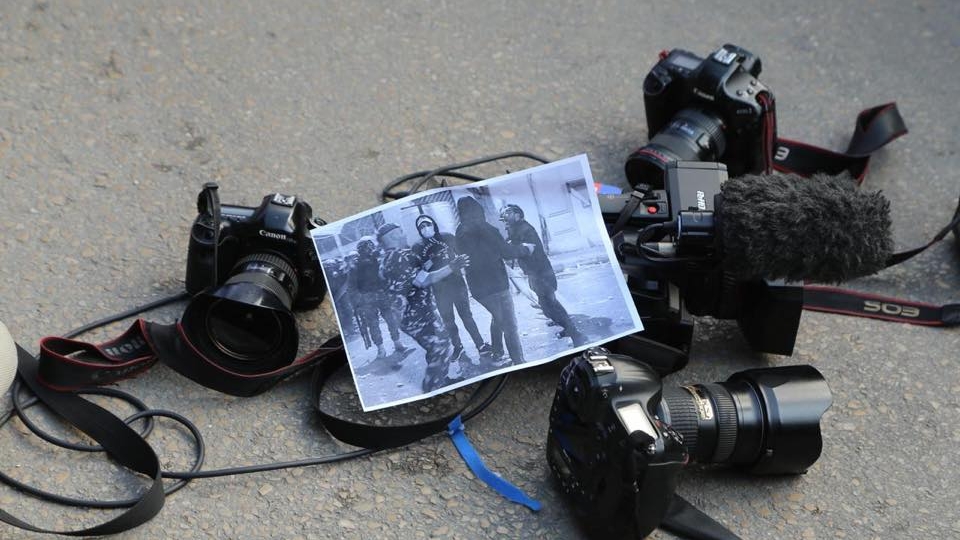

The Revolution was the right momentum for us to create an association as a new framework of mobilization that aims at restoring the role of the Order of Engineers on three levels: Public interest, our profession, and the Order itself,” explains Abir Saksouk, a founding member of the Association of Engineers.The October Revolution seemed to be the right impetus to launch a new pattern of mobilization and hence an association that brings together labor and political mobilization and unseats a state incorporated Lebanese Press Syndicate. The founding statement of the nascent association was disseminated and immediately signed by 180 new members. Soon the association was endowed with six different committees and work of outreach, communication, and organization was launched, and two members were designated to represent the Syndicate at LAP meetings. Very quickly, it started defending journalists who were violently attacked during protests while the official Press Syndicate remained mostly silent when it was not issuing statements in defense of the banking sector after the latter was publicly attacked for illegal capital controls and hidden haircuts at the onset of the Revolution.

Similarly, a group of thirty artists launched the process of labor organizing in their field of work and joined forces with the LAP. Founding member of the association of Workers in Art and Culture Hachem Adnan stressed that “the need to organize goes way before the October Revolution. Way before the 2015 waste crisis. It is a long process that builds up on all our previous mobilizations in the past decade. We now aim to bring together labor organizing and political participation.” The first general assembly of the association gathered around 200 participants.

Also in the first days of the Revolution, a group of thirty engineers started organizing under a new association. One month later, a small committee of five members drafted the internal structure of the association and a set of internal regulations. In Lebanon, engineers and architects are organized under one professional order, the Order of Engineers and Architects, which regulates their practice, healthcare, and pension. Their membership is compulsory or else they cannot practice their profession.

“The organization of the Order of Engineers needs structural reforms to become more inclusive, representative, democratic, and politically engaged. The Revolution was the right momentum for us to create an association as a new framework of mobilization that aims at restoring the role of the Order of Engineers on three levels: Public interest, our profession, and the Order itself,” explains Abir Saksouk, a founding member of the Association of Engineers. This initiative stems from previous reform attempts, the latest being the Nakabati campaign created on the occasion of the Order’s elections in 2017. Today, the Association of Engineers goes beyond the election of a new president. “We want an Order that can play the role of a platform and a pressure group." The association is proposing 160 candidates to the upcoming bi annual-elections of the Council of Representatives which usually comprises 506 engineers. Every two years, 253 representatives are elected (elections were supposed to take place in March 2020 but have been postponed due to the outbreak of COVID-19). Saksouk told me, “we believe that by increasing our presence, as young engineers we can slowly but surely achieve the necessary reforms for a more engaged, representative and democratic Order.” The nascent Association now includes around 120 engineers.

Lessons from Unsuccessful Protests of the Past

This new pattern of mobilizing is not a spur of the moment nor a spontaneous movement. The need for and obstacles to organizing were the subject of continuous discussions and debates among founding members of the LAP for the past couple of years. In fact, this new labor mobilization stands on the shoulder of previous protests, and mobilization attempts. The 2015 mobilization that started with the trash crisis and halted at the end of summer 2015 was an important turning point. The Beirut Madinati experience in the 2015 municipal elections and their ensuing split was also a milestone. These experiences — and heartbreaks — may have set the ground for a retrospective on the need for organizing and overcoming the fear of traditional organizing and frameworks of representation.

[P]rotests in the previous years lacked a representative structure, were sometimes steered by civil society organizations, and were marred by the absence of labor associations.As we know, protests in the previous years lacked a representative structure, were sometimes steered by civil society organizations, and were marred by the absence of labor associations. The absence of labor movements is not proper to the Lebanese case. The role of labor unions is globally marginalized in the context of neoliberal policies that target the downsizing of unionization for the obvious reasons of businesses’ benefit. However, the limited capabilities of structure-less and leaderless movements in dealing with soaring economic grievances and social injustice has now brought to the fore the importance and the need to go back to labor organizing which can guarantee sustainability over time and coordination and geographic spread throughout the country. The co-optation of traditional unions since the end of the Lebanese Civil War aimed to curtail exactly that.

A Promising Context with New Organizational Challenges

One of the major tools of state incorporation of the labor movement in the previous decades was the political elite intervention in representation and decision-making within labor organizations whether unions, professional orders, or public sector leagues, as discussed in Part 1 of this series. Today, the October Revolution, the deepening economic crisis, the financial crash, and ensuing pauperization of the majority of the population has weakened the authority and legitimacy of the ruling elite and traditional patron-client sectarian relations. Like the Arab uprisings, one of the major achievements of the October Revolution so far is the paradigm shift it generated. After decades of simply succumbing to sectarian leadership, citizens have seized the public sphere to oppose the political system and voice their demands and it seems that there is no return to the status quo ante. This context allows a better environment and prospects for the new labor mobilization dynamics and in turn a powerful revolution. In fact, as LAP members often told me, the Arab uprisings were successful in Sudan and Tunisia which are both endowed with entrenched labor movements.

Nevertheless, the nascent LAP faces organizational challenges that need lengthy discussions and probably the envisioning of new approaches to organizing. For instance some organizers I met raised the issue of inclusion and exclusion criteria to their association. Can international professionals be included in these associations? Or how can employees, self-employed, freelancers, and employers organize under one association? For illustration, one can safely say that the needs, demands, and aspirations of young employed engineers are different from those of their employers.

After decades of simply succumbing to sectarian leadership, citizens have seized the public sphere to oppose the political system and voice their demands and it seems that there is no return to the status quo ante.Finally, COVID-19 has globally exposed enduring inequality between two groups of labor as sociologist Antonio Casilli posits: professionals who can safely telework from home or ideally their country houses and manual workers at the other end of the chain — cooks, butchers, bakers, delivery and taxi drivers, and cleaners — who continue working because they are simply indispensable despite everything. COVID-19 shows us that those are the most sacred labor whose protection should be sanctified; a protection that can be seized by a long-lasting Revolution consolidated and strengthened by vital labor organizing, that would sooner or later encompass the essential revival of blue collar organizing.