(Im)Possibilities of Healing Within the Mental Health System

Editor’s Note: This long read begins by concisely touching on the distressing life conditions and methods of suicide experienced by individuals over the past few months in Lebanon. Reader discretion is advised, as the content discussed may be triggering or disturbing to some readers.

“Aloushi, tell Dua’ that Moussa loves her deeply, but I’m tired and disgusted with my life, I can no longer go on. Take care of Jawad, Jury, and Dua’, especially Jury, she is the lump in my heart.” Moussa al-Chami, 31, recorded his last words in a voice note he sent to his friend Ali in March, entrusting him with his family. Moments later, he shot himself near his home in the southern village of Deir al-Zahrani. Moussa had resigned from his post in the army a few years earlier after his wages devalued, and had been moving between jobs, struggling to make ends meet.

In the same month, Hussein Mroueh, 41, messaged his wife to say that he was going for a walk. He was found dead in an olive grove in the southern town of Zrariyeh after he killed himself. In October 2019, Hussein had participated in the popular demonstrations that swept the country and took part in the sit-ins by the Central Bank. For many years, financial difficulties had agonized him.

In late April, Anas Ali al-Musaytef, 26, a Syrian refugee from Manbij in northeast Aleppo, used an electric wire to hang himself in a rented apartment in al-Ghobeiry, a southern suburb of Beirut. During 2017, he fled Syria, fearing compulsory military service. He was struggling with depression, unemployment and substance abuse, especially after spending years in detention at Roumieh prison. His relatives had said that the posts claiming his suicide was related to deportations and crackdowns was untrue.

In early May, 18-year-old Abdelrahman S, a Syrian refugee, was found dead. He had hanged himself in a villa in Ehden, northern Lebanon, where he used to work as a concierge and gardener. Without assuming a direct link, it is worth pointing out that the Assad regime forces registered its highest number of arrests this year, primarily targeting returnees who were forcibly deported by the Lebanese army, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights.

Later that month, the Internal Security Forces reported two cases of self-inflicted deaths within the confines of Roumieh prison. A.T., 32, a Palestinian refugee, ingested spray alcohol, and was immediately hospitalized before his heart stopped. A.K., 16, a non-registered minor, tragically took his own life by hanging inside his cell.

These are some of the people whose mournful stories have grabbed media attention in early 2023 alone. Self-inflicted death sometimes remain unreported, as families refrain from disclosing their loved one’s actual cause of death because cultural and religious norms forbid funeral prayers for suicides.

This year, suicides have already increased by 65 percent in Lebanon, according to The Monthly, a publication by the research and consultancy firm Information International. Internal Security Forces reported 138 suicide cases in 2022; 145 in 2021; 150 in 2020; 170 in 2019 and 155 in 2018. The first and most recent nationwide survey on suicide, published in 2021, reveals that approximately 4.3 percent of the population in Lebanon has experienced suicidal ideation, while 2 percent have made suicide attempts.

In recent years, a chain of tormenting events have rocked the country: a silenced uprising in the Palestinian refugee camps in July 2019, followed by a violently crushed popular uprising in the same year, and a global pandemic in 2020 and 2021. A calamitous explosion tore parts of Beirut on August 4, 2020, and the ensuing movement led by families of the blast victims has since faced intimidation and suppression. Throughout these years, impoverished migrants have drowned in the Mediterranean trying to escape to Europe, as systemic racism against Syrian refugees intensified with forced deportation. All this has unfolded during an ongoing financial and economic crisis of historic proportions, one that resulted in the loss of 220,000 jobs by the start of 2020.

Suicides have already increased by 65 percent this year.

In the thick of the collapse, some alternative media platforms have amplified the conversation around mental health and politics, correlating socioeconomic factors to people’s suffering in a necessary turn against the sensationalist tendencies of mainstream media.

Yet, in her incisive critique of the current mental health discourse, Nour Nahhas, an independent researcher and writer, notes that the prevailing rhetoric of a “mental health crisis” over the past few years got stuck at repetitively concluding an interconnection between the political and the personal. This recognition, she argues, only takes place when the established order is rattled, which betrays the enduring cruel optimism of seeking an impossible fantasy of happiness within a capitalist reality.

In 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) popularized a culturally invariant and binary conception of psychic interiority, as ‘mental health’ or ‘mental illness,’ by prescribing homogenized Mental Health Gap Action Programs in peripheral countries that obscure the neoliberal processes of immiseration and suffering.

Ruins of a possible cistern near Webster House, ‘Asfuriyyeh. Hazmieh, Lebanon. July 13, 2023. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

In alignment with the WHO strategy, the Lebanese Ministry of Health launched its Mental Health and Substance Use Strategy in 2015. The strategy was criticized for adopting a clinical approach to mental illness, which requires medical interventions through psychotropics and therapies, as the state promoted an NGO-ized community-based services model. It framed mental health as a human rights issue, psychologizing impoverished and systematically oppressed groups like the poor, refugees, migrant domestic workers, women, queers, trans-people and children.

The "mental health crisis" rhetoric exposes the cruel optimism of seeking an impossible fantasy of happiness within a capitalist reality.

Recently, the Ministry of Health published a vague mid-term evaluation draft for public review, which included a new mental health strategy for 2023-2030, closely resembling its predecessor.

This article revisits the history of early psychiatric establishments in Lebanon, and looks at how the state has disavowed a public mental healthcare system in favor of a trespassing non-governmental sector. Mental health governance in Lebanon embodies and perpetuates the politics of social numbing, which reproduces a status quo that represses our collective liberation. The piece addresses the political economy of the mental healthcare system, highlighting the limitations of implemented therapy models, and explores other perspectives for subjective healing and social emancipation.

History of Present Illness

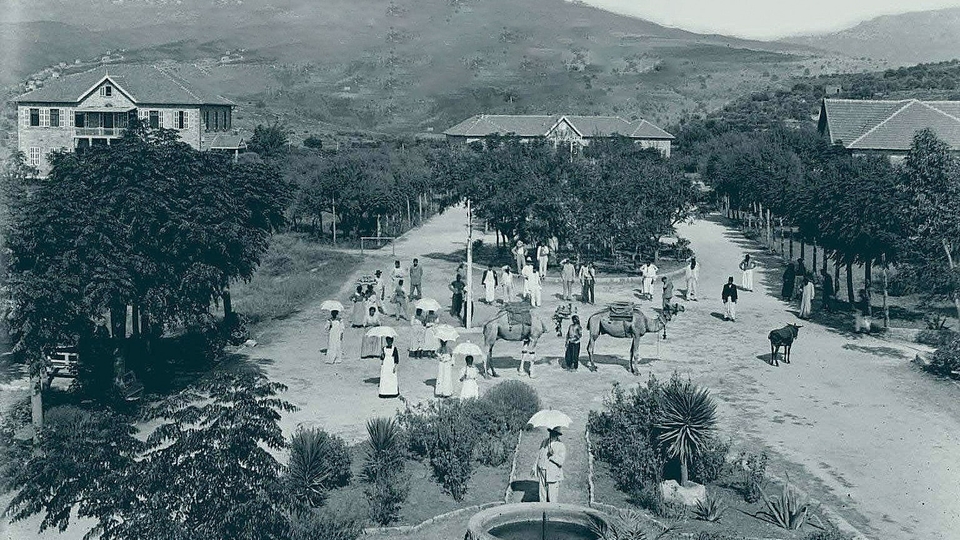

In her dissertation, “Humanitarian Psychology in War and Postwar Lebanon,” medical anthropologist Lamia Moghnieh shows how the 1860 massacres in Mount Lebanon, considered as the first Lebanese war, paved the way for the expansion of missionary and charitable organizations in Ottoman Lebanon.

These missions relied on funds managed by an Anglo-American committee and brought about material transformations in Syria’s political economy and cultural fabric. They were justified by a shared notion of humanity and a moral imperative to protect the Christians of Syria, who were being massacred for revolting against the feudal system.

“European humanitarianism of the 19th century ‘Ottoman Lebanon’ was considered one of the first modern humanitarian military interventions, centered on ‘the right to intervene’ against massacre, as a peculiar form of violence that threatens humanity in its entirety,” according to Moghnieh.

The European reorganization of Ottoman Syria’s population revolved around solving immediate problems, like “the refugees question,” by managing the distribution of aid, planning the resettlement of the displaced, and overseeing a system of punishment and accountability for the perpetrators of killings, remarks Moghnieh.

The unfolding of this humanitarian market in 19th century Lebanon enabled a humanitarian-missionary space for reorganizing the ‘needs’ of the people through education, religious conversion, and emerging medical and psychiatric sciences.

The medicalization of insanity presented an arena for vying colonial powers and missionary organizations; the history of psychiatry in the Levant was shaped and propagated within this context of paradoxical conjunction of colonial exploitation, missionary competition, and local political and cultural reproduction.

The Lebanon Hospital for the Insane, the first psychiatric institution in the region, was founded in 1900 by Theophilus Waldmeier. The Swiss Calvinist turned Quaker promoted the hospital to his European funders as a “project of modernization against violence” to meet the needs of the abandoned and mentally troubled in Syria.

The history of psychiatry in the Levant was shaped and propagated through colonial exploitation, missionary competition, and local political and cultural reproduction.

The hospital was successively renamed the Lebanon Hospital for Mental Diseases in 1915 and the Lebanon Hospital for Mental and Nervous Disorders in 1950. Indian physician and activist Bhargavi V. Davar writes that the “asylum archetype” is a “historical and colonial feature of psychiatry” reworked in time. The metamorphism of the ‘lunatic asylum’ during the 18th and 19th centuries to ‘psychiatric hospital’ in 20th century, then contemporary ‘mental health institution’ subsequently produced variations in sculpting a subject: the ‘lunatic’ turned ‘mentally ill person’ and currently, a ‘person with high support need.’

An all-women photograph featuring patients in working-class attire and medical staff in front of Philadelphia House “for excited female patients,” ‘Asfuriyyeh. Hazmieh, Lebanon, ca. 1904. (SOAS Archives & Special Collections, courtesy of Joelle Abi-Rached)

On a lighter note, historian of medicine Joelle Abi-Rached notes in her book “Asfuriyyeh: A History of Madness and War in the Middle East” that ʿAsfuriyyeh, the hospital’s popular name, derives from the Arabic noun ‘asfour for “bird.” “Curiously, birds have long been used as symbols of freedom… and encaging them… a symbol of confinement and oppression,” writes Abi-Rached, reminding us that “the connotation between madness and birds has been popularized by Ken Kesey’s 1962 novel, ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.’”

But it is uncertain whether birds were connected to madness in ʿAsfuriyyeh, today a part of Hazmieh known for its goldfinches, though it is told that the Ottoman Ahmed Djemal Pasha, remembered as As-Safah among local Arabs, infamous for his extravagant lifestyle, had a golden cage full of singing birds.

In 1919, the Lebanese and francophile Capuchin priest Abuna Yaʿqub, also known as Père Jacques, founded Dayr el-Salib, the Monastery of the Cross, as an asylum for elderly priests. It came as a response to the long-standing rival institution, ʿAsfuriyyeh, which was perceived as yet another Protestant provocation. Dayr el-Salib “succeeded in snatching patients from the Protestant Asylum” until it was converted into a proper psychiatric hospital in the 1950s, according to Abuna Yaʿqub in Abi-Rached's book.

ʿAsfuriyyeh was running entirely on donations and incurred huge debts in the 1960s, as per Abi-Rached. Along with the state’s hands-off position, the civil war accelerated the hospital’s downfall, as right-wing Christian militias who controlled the area frequently terrorized patients and staff. In 1982, a few months before the Zionist settler-colonial army invaded Lebanon, the hospital closed its doors for fear of insolvency.

War in Lebanon has always led to major reconstruction and humanitarian aid projects; the 1880s massacres made ‘Asfurriyeh possible, and its demise in the second civil war gave Dayr el-Salib prominence. Neoliberalization of post-war Lebanon enabled the expansion of private health services, while NGOs replaced the state in governing public (including mental) health by taking over 80 percent of health clinics and dispensaries in the mid-1990s, states Moghnieh in her dissertation.

After the liberation of southern Lebanon from Israeli occupation in 2000, villages like Khiam and Qana became the focus of international aid and humanitarian psychological programs. Furthermore, Moghnieh explains, the 2006 July war called for a massive intervention tailored around a trauma-based prototype. The latter was strongly resisted by an emerging political powers resting on an ideology of “resilience,” conceived as the absence of trauma.

Humanitarian psychological interventions have reduced experiences of violence and suffering to individual psychic injuries that require medicalization and therapy.

With the militarization of the Syrian revolution in 2012, Moghnieh writes that “the Syrian refugee crisis put the humanitarian trauma model once again at the center of humanitarian psychology.” For Syrian refugees, presenting a psychiatrist’s report diagnosing severe PTSD or other evidence of having endured violence influences the chance of receiving aid in Lebanon and asylum in Europe or North America.

Theophilus Waldmeier and his staff at the Lebanon Hospital for the Insane, also known as ‘Asfuriyyeh. Hazmieh, Lebanon, ca. 1907. (American University of Beirut/Saab Medical Library/Digital Archives)

Moghnieh argues that humanitarian psychological interventions psychologized and pathologized experiences of violence and suffering, by reducing them to individual psychic injuries that require medicalization and therapy. Humanitarian psychologists, mental health and social workers were trained to detect trauma and personality disorders in communities by following a strict clinical and psychiatric framework of distress.

Politics of Social Numbing

A 2006 study on the prevalence and treatment of mental disorders in Lebanon revealed that 17 percent of respondents suffered from at least one mental disorder, while only 13 percent have sought medical and mental healthcare. These estimates — susceptible to reporting bias and diagnostic inaccuracy — not only overlook social factors, but are also likely to have increased in these times of prolonged crisis.

Despite these numbers, the Ministry of Health allocates only 5 percent of its expenditure for mental health, of which 54 percent is designated to subsidize inpatient care in private hospitals, according to the 2015 national mental health strategy.

Social spending remains disproportionately low in the national budget, and hardly any private insurance plans cover mental health services. Today, 45 percent of the population lack any form of insurance, a number reflecting that those who are most in need have the least coverage.

According to the national strategy, public mental health facilities, NGOs, and private clinics were already understaffed in 2015, with an estimated: 1.26 psychiatrists, 2.26 nurses working in mental health, 3.42 psychologists, 1.38 social workers in mental health, and 1.06 occupational therapists per 100,000 people.

With the onset of the current crisis, around 3,500 general doctors have left Lebanon; the exact number of psych-professionals who have left since 2019 remains unknown.

Free mental health services are provided today through NGO centers, most of which are concentrated in the capital. The lack of available public and private services in peripheral areas forces individuals to travel long distances, if they can afford the costs of transportation, to receive quality care. Mental health services are poorly integrated in the scattered 200 primary health care centers affiliated with the Ministry of Public Health, according to recent studies.

Apart from establishing the rehabilitation unit for substance use at Dahr el-Bachek Hospital in 2014 and another inpatient unit at Rafic Hariri Hospital in 2018, the government has not set up any public center for mental health services.

Patients diagnosed with opioid use disorder based on the DSM-V criteria would be registered to receive weekly take-home buprenorphine from the Ministry of Health's centralized dispensing unit at Rafic Hariri Hospital.

Skoun, a local NGO offering free treatment for substance users, operates the unit; the cost of monthly treatment ranges from $85 to $250, according to Nada Kaii, a senior psychotherapist at Skoun.

With the public health crisis, pandemic, and growing inflation, “the Ministry is no longer accepting new patient files [and is] denying help to more people who desperately need it,” Kaii tells The Public Source.

The crisis has also been devastating for people undergoing treatment. “The crisis forced us at Skoun to reduce the quantity of prescribed medications,” she says. This led to “treatment relapses, side effects, and [only] 7- to 10-day programs” of detoxification in hospital, “shorter than what is usually recommended.”

None of this is surprising when a political economy governing drugs and mental health conspires against those who need it the most. Today, out of 146, only five major importers of pharmaceuticals monopolize 53 percent of the Lebanese market, flooding it with prohibitively expensive, patented drugs, largely produced in the West.

“The Ministry of Health is no longer accepting new patients and is denying help to more people who desperately need it.” Nada Kaii, psychotherapist at Skoun

The laissez-faire economy established in the 1950s and 1960s generated some $650 million of declared profits in the last decade for these well connected importers, a couple of which have been in business since Ottoman rule. Meanwhile, the Lebanese state shoulders a hefty drug bill per capita, accounting for 44 percent of total health expenditure in 2018 — by far the highest in the region pre-crisis.

The National Social Security Fund (NSSF), which used to cover medical examinations, in-patient and out-patient services, and 80 percent of medication costs (including psychotropics) for approximately 840,000 subscribers in 2017, is collapsing.

The medicalization of suffering in Lebanon, as elsewhere, has created a lucrative market for pharmaceutical monopolies, favoring local importers and Euro-American producers.

Ruins of Webster House which was built in 1937 to house the forensic unit. It was occupied by the Australian army during the British colonial invasion of Syria and Lebanon in the second world war, ‘Asfuriyyeh. Hazmieh, Lebanon. July, 13, 2023. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

Neoliberal policies have meanwhile bowdlerized the Lebanese Food Drugs and Chemicals Administration (LFDCA). Founded in 1957, the official regulatory body remained partially functional, conducting chemical compound tests for drugs over the span of five decades. Despite its limited resources in terms of equipment and trained staff, the LFDCA played a crucial role not only in technical matters, but also in a legislative capacity for generic drugs.

In 2007, the national central laboratory located in Ain el-Tineh was demolished “for security reasons” and incorporated into the nearby second presidential residence.

The medicalization of suffering in Lebanon, as elsewhere, has created a lucrative market for pharmaceutical monopolies, favoring local importers and Euro-American producers.

The cessation of the laboratory allowed for loopholes in the examinations of domestically produced and imported medical drugs. Today, private laboratories for generic drug examinations lack standardized pricing, charging hundreds of dollars for in-house analyses, and escalating in the thousands for samples examined outside; these fees are initially borne by importers and, at a later stage, recollected in doubled profits from patients’ money.

“People are breaking off their medication or decreasing prescribed dosages, fearing a sudden interruption to their treatments due to shortages of psychotropics and rising prices,” Myriam Zarzour, a psychiatrist practicing privately and co-directing the Embrace clinics, tells The Public Source.

“We can’t be sure about the efficacy of many generic drugs that are replacing the brand names due to a lack of drug examination and analysis,” she adds.

Embrace Mental Health Clinics opened in Hamra to offer free psychiatric consultations, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and brief psychodynamic sessions following the August 4 explosion. It also operates the national line for suicide prevention (1564) in collaboration with the Ministry of Health.

“I could only afford to follow up with a psychiatrist or a neurologist in a private clinic when I had a full-time position. The doctor’s fees became a burden, and finding someone who charges less than $40 is almost impossible today,” Dana Kazma, a communist queer organizer, shares her personal experience with The Public Source.

“I find myself trapped in a dilemma,” she reveals. “Do I keep seeing my psychiatrist? Do I change my medications, or should I stop taking any, since I don’t have a stable job?”

“These are the times when individuals require professional assistance the most,” she concludes on a solemn note.

Besides psychiatric services, therapies used in the mental health programs of NGOs are limited to brief CBT and psychodynamic therapies. On average, these therapies consist of 12 sessions of 45 minutes each, during which the patient is offered “tools” to adapt to their wretched reality, explains Anna-Maria Saleh, a psychotherapist who practices in her private clinic in Tripoli and works with NGOs.

Football prints on one of the walls of Webster House. Youths have reclaimed the former forensic unit in ‘Asfuriyyeh. Hazmieh, Lebanon. July, 13, 2023. (Marwan Tahtah/The Public Source)

“In pursuit of scientism, psychiatry parted ways with psychoanalysis and adopted CBT, which can sometimes be counter-revolutionary because it fosters conformity,” Hadi Boustany, a Berlin-based psychiatrist in-training, states in an interview with The Public Source.

“In a certain amount of time,” he explains, “you have a therapist who assumes a moral position and gives you ‘tools’ to reinforce your ego. The work done in CBT is exactly what you try to undo in psychoanalysis.”

“In pursuit of scientism, psychiatry parted ways with psychoanalysis and adopted CBT which can sometimes be counter-revolutionary because [CBT] fosters conformity.” Hadi Boustany, psychiatrist in-training.

“Generally, NGOs avoid psychoanalytic treatment under the pretense of its longer duration, which implies higher costs. They primarily worry about reporting ‘case numbers’ to funders at the end of each funding cycle,” Saleh discloses to The Public Source.

“This [avoidance] also stems from a presumption that ‘vulnerable’ individuals are unable to investigate their inner lives and histories,” she adds, intimating that these presumptions are not free from bigotry – if not classist, racist, and colonial sentiments of superiority.

Humanitarian psychology always works with “known knowns,” things they already know or assume that they know, based on evidence; it is obsessed with prediction and control. Zarzour is at least partly informed by this logic.

“NGOs avoid psychoanalytic treatment [based on] the presumption that ‘vulnerable’ individuals are unable to investigate their inner lives and histories.” Anna-Maria Saleh, psychotherapist

“People are trapped in despair and uncertainty, unable to plan for the future… but there are a few things I know, so I try to shift my focus there and I encourage my patients to prioritize their own well-being and personal growth by consistently controlling their symptoms with medication. This gives a feeling of certainty,” she says, explaining her approach to The Public Source.

“Until the broader image becomes more transparent, it is very important to hold onto hope; there must be a light at the end of the tunnel, although we can’t see it now,” Zarzour maintains.

Interestingly, Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek wrote that true courage lies in acknowledging that the light at the end of the tunnel is probably the headlight of another train approaching us from the opposite direction.

Saleh explains that mental health programs operated by NGOs are characterized by their short-term duration, lasting up to six months, and usually renewed for a few years. She expresses her concerns around this model. “What will happen to the patients who depend on NGOs for psychotropic and chronic medications when NGOs terminate their programs?” she asks in worry.

In 2015, funds covering mental health programs for Syrian refugees were abruptly suspended. In her ethnography, Moghnieh documented this sudden lack of funding, which intersected with UNHCR’s declaration that it was halting refugee registrations in compliance to a request by the Lebanese government.

“What will happen to the patients who depend on NGOs for psychotropic and chronic medications when NGOs terminate their programs?” Anna-Maria Saleh, psychotherapist

A further investigation is needed to assume a direct link between suspension of funding and refugee registration. In another “coincidence,” the deportation of thousands of Syrian refugees began one month after an IMF staff statement in March of this year that concluded that “the presence of a large number of refugees exacerbates Lebanon’s challenges.”

By conceiving mental health as a human rights issue and abiding to global humanitarianism, the national strategy reproduced a political economy around mental health defined by transience and instability and shaped by the shifting agendas of donors.

The Communal Is Political

The national strategy encourages a community-based framework, albeit NGO-operated, and may recognize poverty as a major factor of psychic distress in its situational analysis. Yet, the prevalent mental health approaches today largely focus on trauma and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as understood from a westernized clinical perspective. This approach has long been criticized by local professionals and researchers for its failure to address the structural barriers in the way of communal healing.

“Qaderoon – We Are Capable” is a mental health program developed by the Public Health department at AUB in collaboration with Palestinian NGOs in 2007. The aim was to provide the Palestinian youths of Burj al-Barajneh refugee camp with psychological skills and resources to prevent mental distress. A subsequent assessment revealed that the juveniles were negatively impacted by this program, as it failed to address systemic impediments and inequalities, putting the “effectiveness” of such interventions at question, as documented by Moghnieh in her ethnography.

“Traumatic events cannot be banished from consciousness when they are not banished from communal reality”, psychiatrist Samah Jabr reminds us, in an interview by Lara and Stephen Sheehi in “Psychoanalysis under Occupation: Practicing Resistance in Palestine.” Jabr stresses the necessity of approaching trauma through settler-colonial realities, beyond the bounds of individual psychotherapy. Countering the Israeli colonial policies in occupied Palestine is paramount in trauma intervention and peacebuilding.

“The DSM shapes and constructs the subject through a hyper individualized and biomedical lens,” Kazma is convinced. “It employs a categorical and pathological terminology [that] transforms [us] into what is textually inscribed.” This approach, she says, “conceals the socio-economic conditions causing our symptoms.”

“Traumatic events cannot be banished from consciousness when they are not banished from communal reality." Samah Jabr, psychiatrist

In “Psychoanalysis and Revolution,” a manifesto for liberation movements published during COVID-19 lockdowns, psychoanalyst Ian Parker and philosopher David Pavón Cuéllar write that “the constitution of the individual is social and cultural, but also historical, which makes it incessantly transformative.” Psychoanalysis perceives symptoms as double historical phenomena: they are produced by a personal history and their overall manifestation is socially determined.

Psychoanalysis is the subject’s assumption of her own history articulated in words. Through speech and listening, we depathologize our symptoms and contextualize our personal histories in social realities. Addressing the communal aspect of our individual experiences moves the conversation on psychic healing back to politics, for what we experience communally is always political.

“I see a revolutionary aspect in listening to the unconscious and being present for the worker, the proletarian, to help them realize the chains. Class consciousness needs speech to surface from the unconscious,” reflects Boustany. That’s why he believes pushing psychiatrists to adopt the tools of psychoanalysis in their clinical practice is “a political task.”

During the 1920s and 1930s, the psychoanalytic practice was first developed as a welfare endeavor at the margins of Western culture. With the rise of Nazism and the closure of free psychoanalytic clinics in various European cities, it was rendered a bourgeois activity.

Jacques Lacan visited Lebanon and Syria in 1973. The trip was organized by his student Adnan Houbballah, one of our country’s pioneer analysts. In 1974, the latter relocated to Beirut with his family, alongside his fellow returnees, he introduced Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis. Also, he co-founded the Lebanese Society for Psychoanalysis (société libanaise de psychanalyse) in 1980. Over five decades later, psychoanalysis remains an elitist activity in Lebanon, mostly pursued by an urban and educated middle class.

In “Freud’s Free Clinics: Psychoanalysis and Social Justice,” professor of social work Elizabeth Ann Danto brilliantly retrieves the repressed history of early psychoanalysis.

“For the archeologist, the reconstruction is the end of his endeavors while for analysis the construction is only a preliminary labor,” writes Freud in a short essay titled “Constructions in Analysis”, published in 1937. A wooden divan and chair in a public psychoanalytic clinic, seemingly inspired by the communist furniture designer Enzo Mari. Vila Itororó, São Paulo, Brazil. (Clínica Pública de Psicanálise/The Public Source)

We learn from Danto that in 1918, during the Fifth International Psychoanalytic Congress in Budapest, Freud called on the psychoanalysts in attendance to open “institutions or out-patient clinics [where] treatment will be free.” He considered flexible fees and free clinics as a materialization of collectivity within psychoanalysis, and supported them throughout his career.

Many of the early generation of analysts were militants in leftist political organizations; they set out to fulfill their social duty and build free clinics in several European cities. “They were free clinics literally and metaphorically: they freed people of their destructive neuroses and they were free of charge,” Danto writes.

Rather than consuming ourselves in repetitively linking mental health to crisis, investigating the relations between psychoanalysis and political praxis may unfold new possibilities for our collective emancipation. By returning to the history of psychoanalysis, we can reconnect it to our liberation movements and contradict the false hopes and impossible fantasies perpetuated by humanitarian psychology.

“[Psychoanalysis clinics] were free clinics literally and metaphorically: they freed people of their destructive neuroses and they were free of charge,” Elizabeth-Ann Danto, professor of social work

Parker and Pavón Cuéllar invite us to remember the free clinics of psychoanalysis in early 20th century Europe and to recognize — and learn from — similar initiatives that have been developed over the past decade in the favelas of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. These initiatives consider the linkage between state violence and psychic suffering, and offer free psychoanalysis to a wider public of lower-middle class and poor people. The writers argue that such recognition allows for a genuine psychoanalytic transference to take place, rather than a payment-induced dependence for someone that we assume has something important to say about us, although it is always the analysand who analyzes.

Kazma, a psychology graduate currently undergoing analysis to become an analyst herself, contemplates the idea of building free clinics across Lebanon. “An open clinic can be a space to radicalize professions”, she says, ”so it is crucial to allow a political collectivity among people working together to emerge from a shared communal responsibility. The envisaged work would be pioneering [in our local context] and therefore continuously unfolding, devoid of predetermined expectations.”

Parker and Pavón Cuéllar remark in their manifesto that psychoanalysis, a practice emerging from the hysterical world, makes space for a hysteric expression to be heard and does not perceive it as a disorder. As an experience of truth and a logical response to oppression and power, a hysteric expression can be of interest to and utility for liberation struggles.

The bright “nights of the Molotov” saw protesters vandalize and burn dozens of banks in Beirut and Tripoli during the October 17 uprising; these violent protests intensified the class struggle between the “civil” and the “popular.” State media hystericized and infantilized the enraged protesters by depicting them as immature and reckless people. The aim of this tactic was to shift the focus away from the initial violent act — that is, denying people their own savings in the banks — toward criminalizing the popular expression of anger.

A hysteric expression is an experience of truth and a logical response to oppression that can be useful to liberation struggles

Various concepts of psychoanalysis can also help us better grasp our long history of failures within political organizing; like when we unconsciously repeat the same old failed strategies because we enjoy waiting for an expected outcome to shield ourselves from the unforeseen. This repetition is experienced as a form of suffering.

In the clinic, this enjoyable suffering can be untangled and overcome through verbalization and insight. However, it is not a repetition of sameness but a repetition harboring a difference that we can recognize and learn from; since it is only in repetition that there can be change.

A public psychoanalytic clinic at the famous Vila Itororó in São Paulo which used to house dispossessed people between 2005 and 2006. Before the fatal spread of Covid-19 in Brazil, the Public Clinic of Psychoanalysis was operating in parallel with the reconstruction and rehabilitation works that transformed this historical edifice into a public cultural space. Vila Itororó, São Paulo, Brazil. (Clínica Pública de Psicanálise/The Public Source)

Although psychoanalysis won’t tell us how to strategize the revolution, it can still be useful for militants and within our political organizations.

It is not only a question of ‘what can psychoanalysis offer militants?’ but also, ‘what can militancy offer analysts?’ This requires locating psychoanalysis in history; one might try to fulfill this task by studying the political economy of clinical work.

In his exceptional book on “The Desire of Psychoanalysis,” Brazilian philosopher and psychoanalyst Gabriel Tupinambá argues that examining the political economy of clinical practice evokes implications for psychoanalytic thinking itself. “[It] can possibly promote meaningful transformations in the scope of analytic interventions and allow us to propose more rigorous exchanges between psychoanalysis and other fields of thought,” he writes.

In a world where psychoanalysis is impossible but necessary, our task is to build another world in which psychoanalysis is possible but unnecessary.

We can only interpret our unconscious worlds in psychoanalysis clinics. However, the point for militants is to consciously change the world through political organizing. Philosophers have theorized the subject of psychoanalysis as one of politics, and stated that psychoanalysis can only successfully end in the political realm with the abolition of patriarchy and capitalism, which would allow for sculpting different subjectivities and symptoms.

In a world where psychoanalysis is impossible but necessary, our task is to build another world in which psychoanalysis is possible but unnecessary.

Correction: The author of “ʿAsfuriyyeh: A History of Madness and War in the Middle East” is Joelle Abi-Rached, not Joelle Abi Khater as it had appeared in an earlier version of this article. The earlier version also misattributed a quote from Abi-Rached's book to the author herself, saying Asfuriyyeh “snatched patients” from Dayr el-Salib, when in fact it was Abuna Yaʿqub, the founder of Dayr el-Salib mentioned in the book, who said that. Both of these errors have been corrected.