The Student Movement in Lebanon, a Struggle Through Time

In 1882, the dean of the Syrian Protestant College — now the American University of Beirut — gave a speech in which he professed support for Darwinism. Religious students from the Faculty of Medicine and the Faculty of Arts and Sciences gathered in angry protest, creating crisis for the administration and culminating in the dean’s dismissal. Encouraged by the success of their organizing, students decided to meet regularly to discuss their needs and demand responses from the administration. What they received was repression, coercion, and arbitrary expulsions. The incident is the first recorded instance of a student movement in Lebanon’s modern history.

Nearly a century later, the student movement reemerged, once again at the Syrian Protestant College. At the time, bourgeois institutions and foreign missionaries monopolized higher education, making it accessible only to the upper-middle class and excluding the impoverished popular class — an exclusion that ended only in the 1950s with the establishment of the Lebanese University. During the First World War, young men across the Levant, among them students, rose up to protest compulsory military conscription. To suppress the rebellion, the Ottoman sultanate executed tens of them.

The student movement also mobilized for liberation and anti-colonial struggle as French hegemony emerged in the region. Lebanon is said to have witnessed its first mass protests in 1925, when student demonstrations against British Foreign Minister Arthur Balfour’s visit to Jerusalem ignited protests throughout Beirut and Damascus. Pan-national liberation causes also left their imprint on the student movement: In 1937, students staged a sit-in to protest Turkey's annexation of Alexandretta and Cilicia; in 1941, they organized marches in solidarity with Iraq’s independence from British colonial rule. Students were also central in the fight for Lebanese independence from French mandate rule, playing a leading political role in the popular uprising.

Student action also became the backbone of social and economic protest. Perhaps the most important was the late 1940s strike against Société Tramways et Éclairage de Beyrouth, the French-Belgian franchise that managed the tramway, in protest of the hike in ticket prices. Students succeeded, within a month, in reducing the number of tramway passengers to zero.3

In the early 1950s, students at Saint Joseph University rallied to establish a national university accessible to lower social classes. It took them almost a decade of mobilizations and strikes to achieve their aim — years after the entity, the Lebanese University, had been officially decreed. The Lebanese University matured the student movement, and the organizational experiences between the late 1960s and mid-1970s institutionalized it. The movement reached its peak with the formation of the National Union of Lebanese University Students, and the proliferation in private and public colleges of student clubs and syndicates as well as teachers’ associations. The Union, which headed and shaped the direction of the student movement, had leaders from the political left and right, who alternated and operated in a relatively democratic fashion despite the politically and economically charged context.

In that era of social protest, the student movement was at the fore, fueling the “Year of Rage” (1972), committing to labor and popular causes, supporting tobacco workers at the Régie (the monopoly tobacco company), defending tenants’ rights and those of Palestinians to armed struggle. University and high school students alike fought by holding conferences, presenting technical programs, unifying their demands, and organizing protests, sit-ins, and general strikes. They blocked roads and stormed ministries and administrations across Beirut, Tripoli, and Sidon. And they met the brutality of the security forces; some were arrested, some wounded, others killed. None of the Lebanese University’s faculties would have been built otherwise.4

The movement’s glow dimmed with the onset of the civil war. Academic calendars were frequently interrupted, particularly at the Lebanese University, whose buildings could become arenas of confrontation between combatants. After the Taif Agreement was signed declaring the end of the civil war, the early 1990s brought a deteriorating economy and currency devaluation, which propelled popular mobilization. During the phase of reconstruction and implementation of Hariri’s neoliberal economic plans, the country witnessed an important wave of social protest, as movements of workers, employees, and students demanded human rights such as the improvement of educational and working conditions. In 1995, Hariri’s government banned protests and launched a two-year crackdown on the labor movement that ended with the dismantling and containment of the General Labor Union.

Private university students have protested against tuition fee increases several times since the 2000s. Likewise, over the past decade, contract professors in public education have led a prominent movement to demand rank and salary adjustments. The October 17 uprising witnessed the spontaneous return of primary and secondary school students to the streets, which contributed to fueling the uprising during its first weeks. Protesting the deteriorating living conditions and the dire state of the education system, university students and educators from public and private schools organized marches and strikes inside academic institutions, the Ministry of Education, official administrations, and protest spaces. What followed was a significant change in the political landscape, as reflected in student electoral races at private universities where secular and independent clubs defeated clubs affiliated with establishment parties. By the end of 2020, repressive security forces acting with their typical brutality reminiscent of the violence of decades prior, cracked down on the movements that were demanding support for public education and defying the government’s decision to dollarize tuition fees and consolidate class exclusion.

Today, the fate of more than eighty thousand students, dispersed across the branches of the Lebanese University, hangs in limbo as the crisis deepens and accelerates due to the state’s indifference. And the future seems to have been cancelled for university professors who have faced many interruptions in recent years to their struggle to recover the rights they are owed.

To animate the historical context and parallels of Lebanon’s student movement, we are republishing a selection of photos from the archives of Assafir.

Following the student elections of 1974, the National Union of Lebanese University Students called off its open-ended strike, which was no longer yielding results, and switched to student marches. Beginning at different colleges and universities, the marches quickly turned into popular demonstrations that security forces confronted with force. This photograph was taken on March 5, 1974 during a student march headed to Nejmeh Square. One sign reads: “The National University should be a factory that produces specialized cadres, not a temporary prison for those deprived of work and specialization.” On a smaller sign: “Haigazian College.”

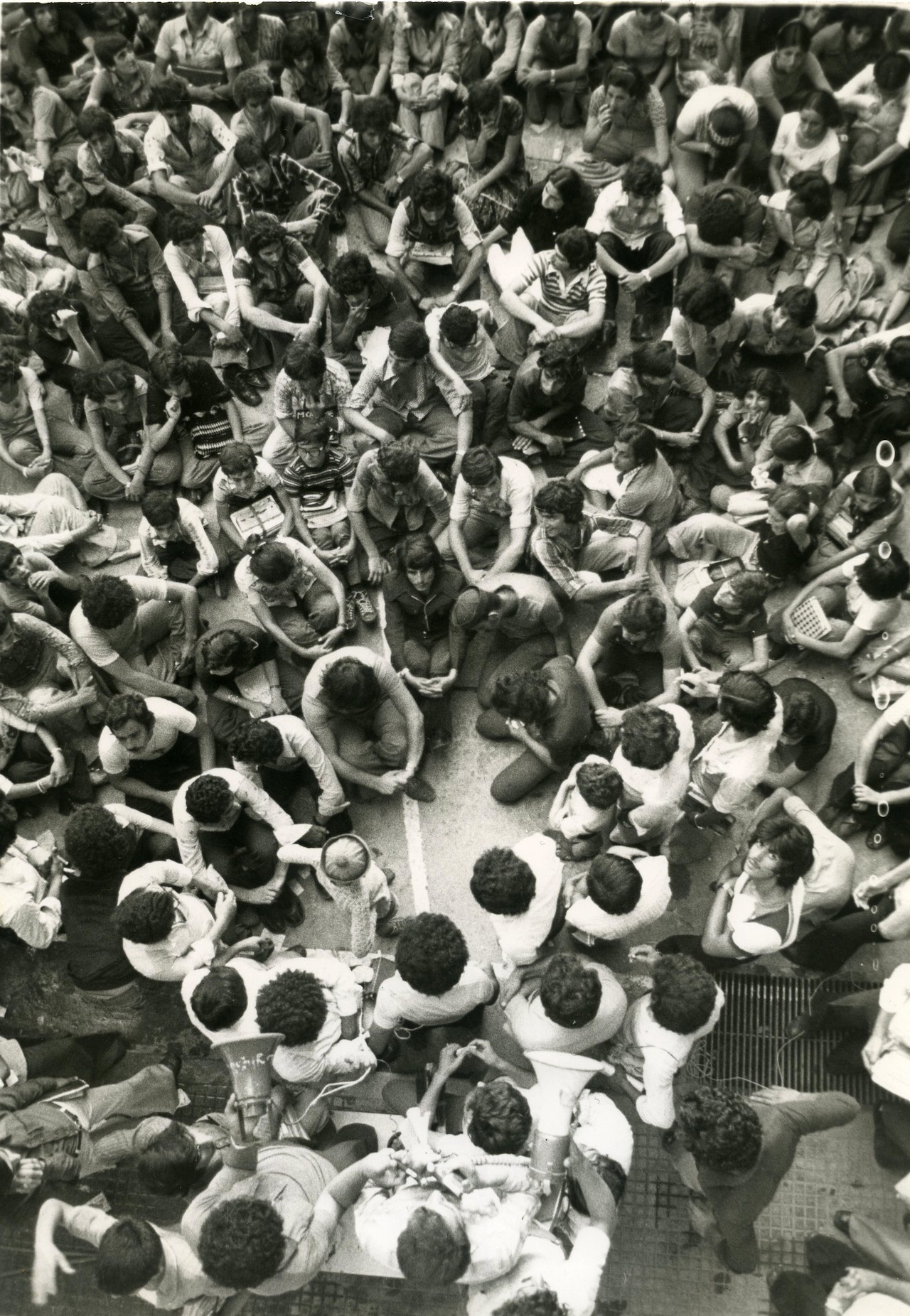

A scene from above: A crowd of high school students sits in their school playground after completing a march on March 27, 1974, listening to a fellow protestor. High school students and their teachers marched in different regions, demanding universal access to a high school education, improvements to curricula, and promoting teachers to full-time positions. They also demonstrated in protest of security forces’ repression of the student movement, chiefly the arbitrary arrests.

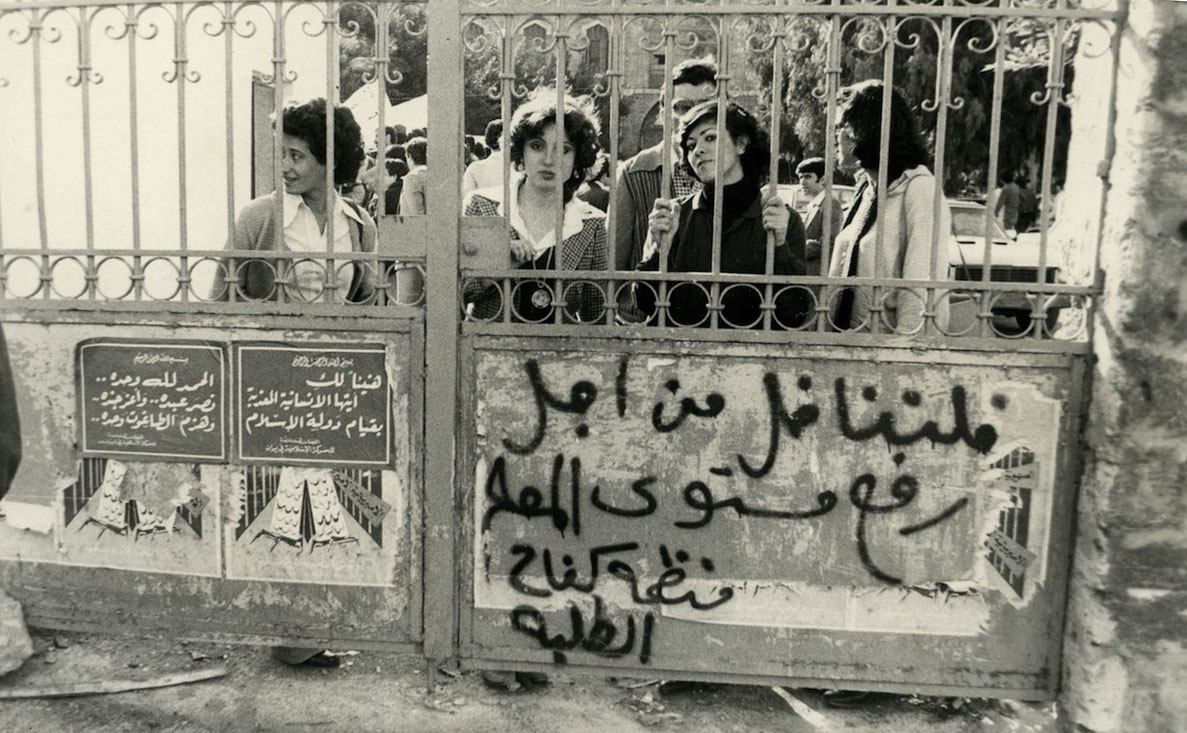

An undated photograph of a demonstration in front of the Faculty of Law in Sanayeh (what is now the National Library). A group of students stand behind the college gate, the right half of which is tagged: “Let us fight to raise the level of education (or of the teacher),” signed, “The Organization for Student Struggle.” On the left half of the gate are two posters signed, “The Committees in Solidarity with the Islamic Movement in Iran.” The first poster reads: “Congratulations to you, oh tortured humanity, for the rise of the Islamic State.” The second contains a quote from Takbeerat Al-Adha: “Praise be to God alone.. Gave Victory to His slave.. He strengthened His soldiers.. He defeated the Taaghout alone…”

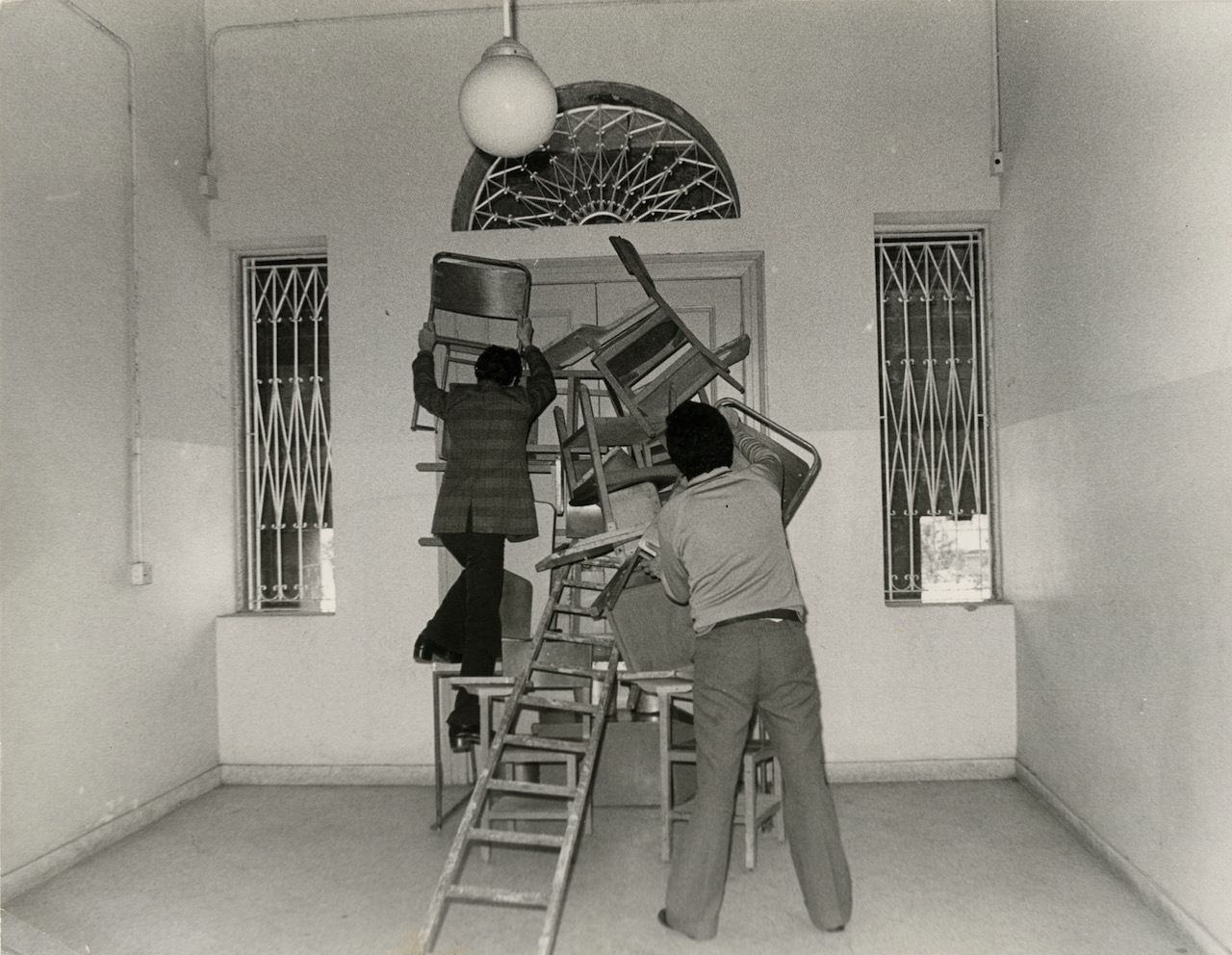

In 1974, in protest of the 10 percent increase in tuition at the American University of Beirut, students occupied the university president’s office and asserted control over all of its buildings and entrances for 37 days. The sit-in ended with security forces storming the university and arresting 61 students. The administration later issued an order to suspend over 100 students. In this photograph, two students block one of the entrances with tables and chairs.

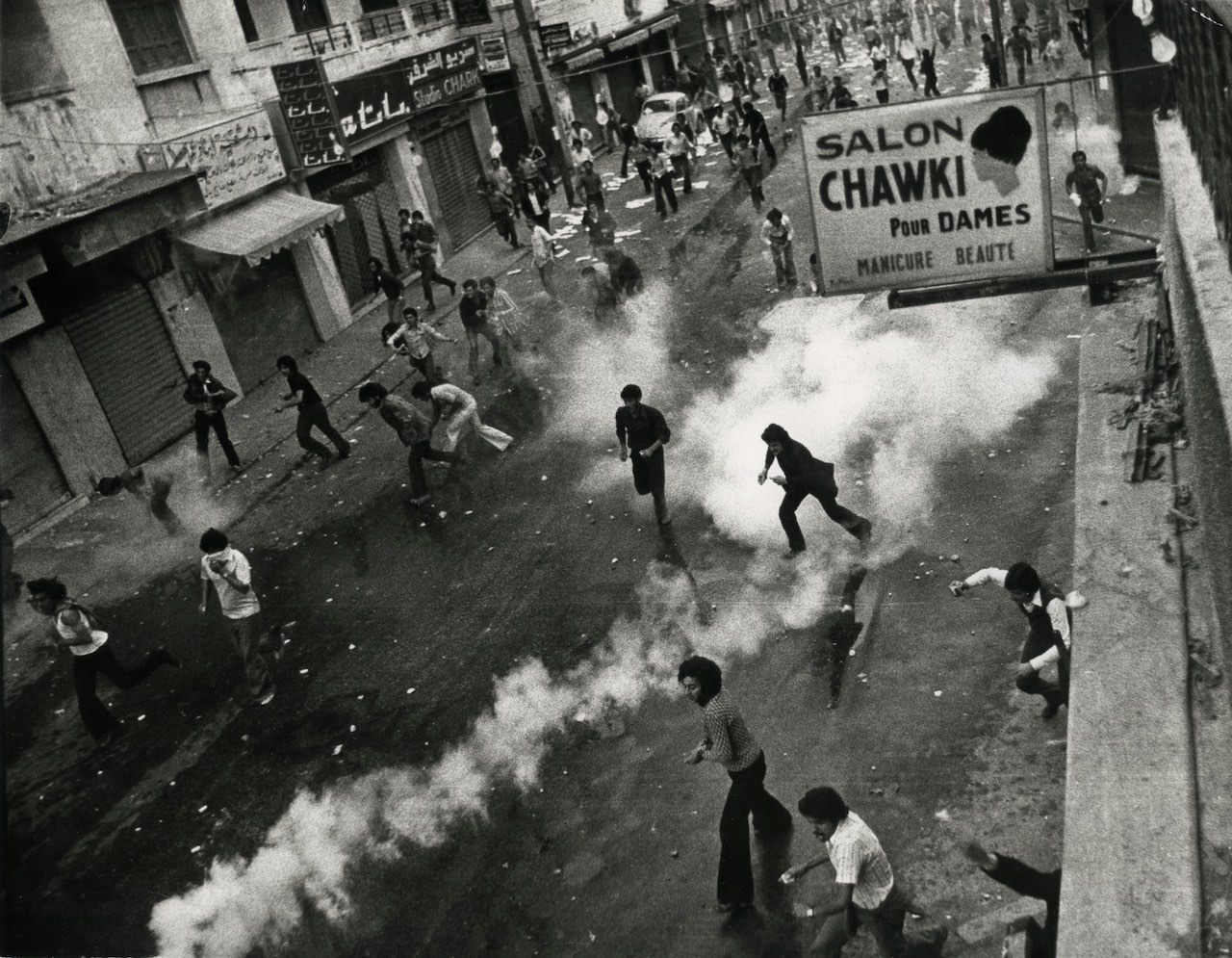

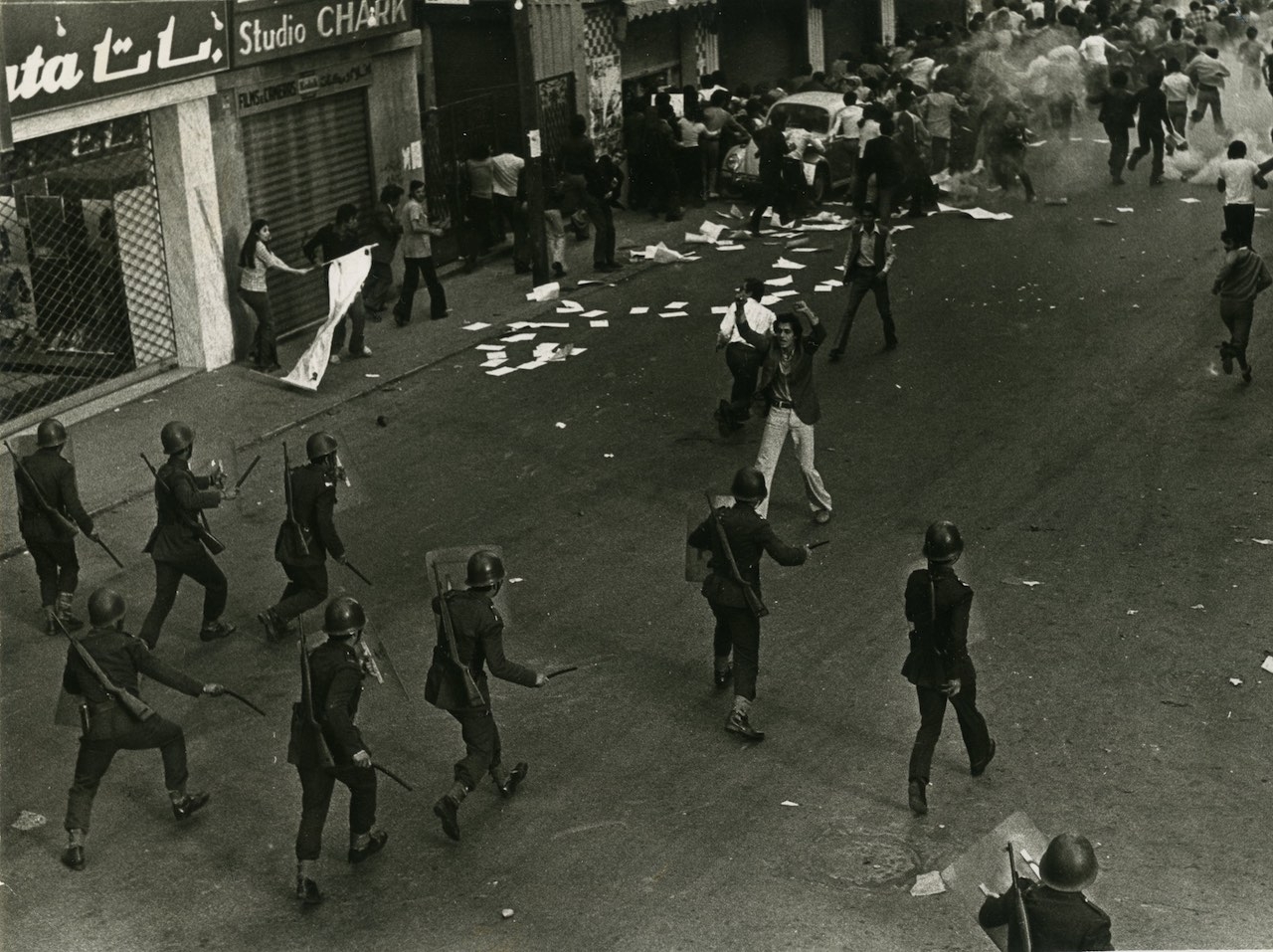

After security forces stormed the American University of Beirut, revenge demonstrations erupted, sparking violent confrontations with the ruling class and its guards. In the photograph, dated February 26, 1975, is a scene from one of the confrontations on Hamra Main Street, where tens of students charge, amid tear gas, some of them armed with stones.

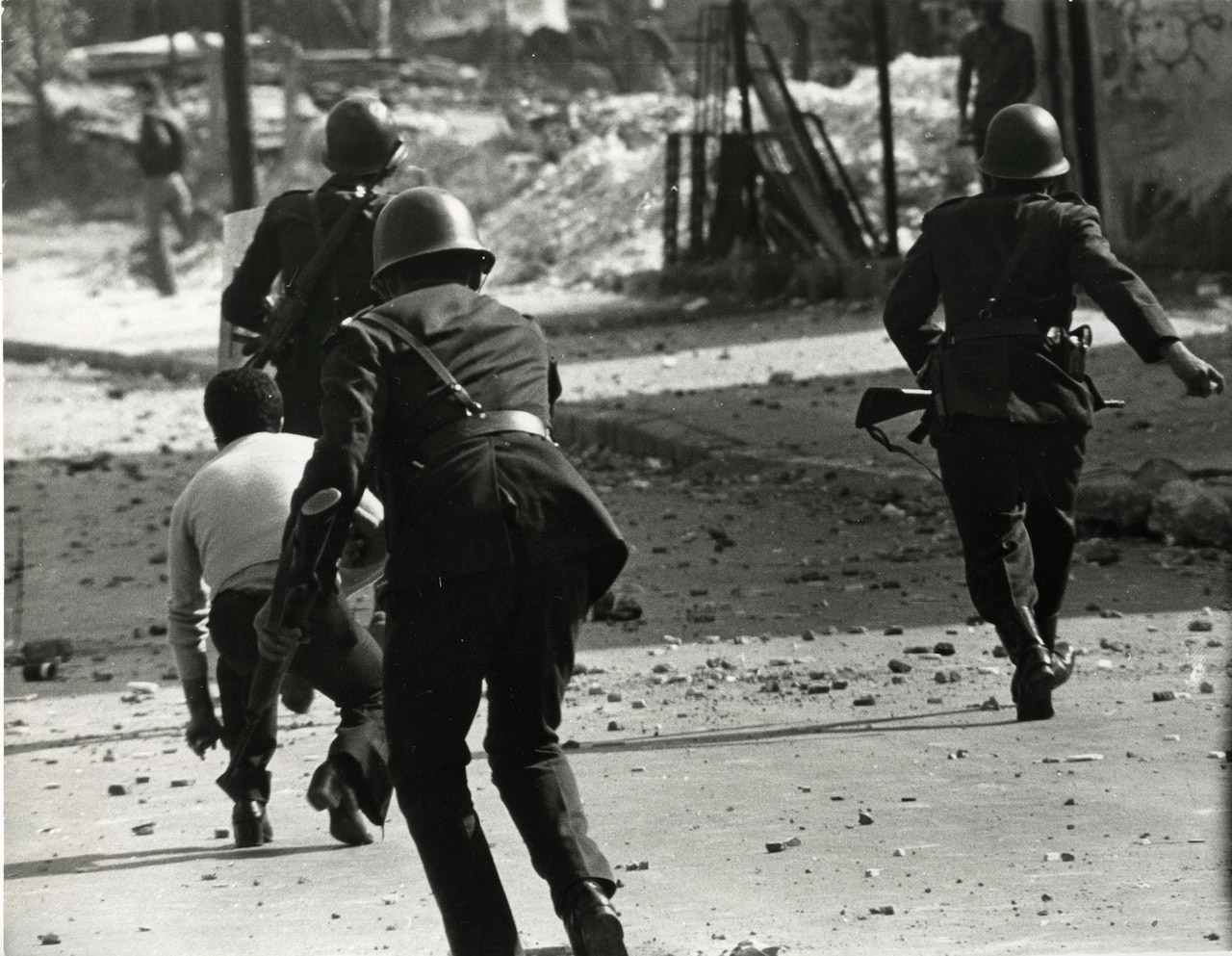

A photo from the aforementioned confrontation on February 26, 1975, on the back of which the following sentence is written: “ … And the students chant: we are greater, oh soldier!” A chant that resounds to this day.

Three members of the military, armed with stones and guns, chase students into the streets, after storming the American University of Beirut and breaking up the sit-in on February 26, 1975.

A scene from the attacks of riot police on students during their demonstration in front of parliament in 1973. Written on the bus board: “Martyrs’ Square, Central Business District, Verdun, UNESCO.” It is likely the photographer took this photo from the Azarieh parking lot.